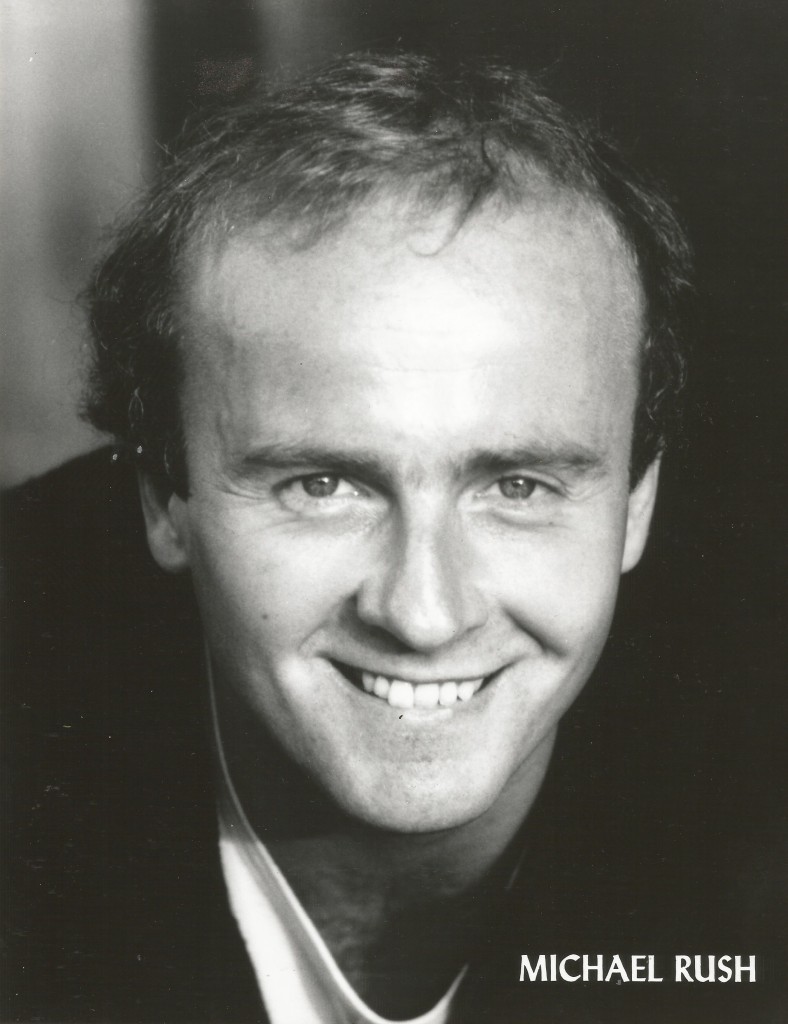

Michael Rush died this week of pancreatic cancer. He and I had completely lost touch in recent years, and it’s been over 20 years since he last did any theater in Connecticut. But for a time in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, he loomed large in the New Haven arts scene. He inspired and he originated. He led by example. Through his art, and as an artist, he left lasting impressions.

Michael was one of the purest practitioners of “performance art” that I’ve ever known. That’s because he came from both a performance place and an art place. He was an accomplished actor and singer who eased confidently into directing when he saw a lack of projects that fit his multi-disciplinary interests. He also had a lifelong love for the visual arts—as a critic, as a historian, as a curator and, when I knew him, as the artistic director of New Haven Artists’ Theater.

NHAT was a low-budget company whose work never looked cheap. Michael Rush did things with worklights and bedsheets that made you think he’d rented a cyclorama and Fresnels. He’d make small, tight spaces look grand. He’d overcome all sorts of restrictions—dance spaces where you couldn’t build or store set pieces, a limited pool of available actors who shared his vision, scheduling issues and all the other crises that beset small companies—and create perfectly composed, completely original gems of modern art/theater.

He would incorporate countless visual and performance ideas into these pieces, then strip them down to their essence. He created performances that directly referenced famous psychologists, avant-garde playwrights and postmodern playwrights yet did so in a way where those inspirational figures’ styles did not overwhelm the performances’ own shapes and outlooks.

My friend Hillary Kelleher, who appeared in one of the first NHAT productions, and I would joke about how Michael had explained to the cast that mastering the butoh walk could take a lifetime, then casually say “Let’s do it now,” butoh-walk for a few minutes, then move onto some other major theoretical framework for whatever the next scene might be. Yet somehow, amazingly, the New Haven Artists’ Theater shows didn’t seem overthought. They certainly weren’t busy. They felt full and lush despite very sparse trappings (usually just curtains and projection screens). They had focus, leisurely timing, a meditative mood.

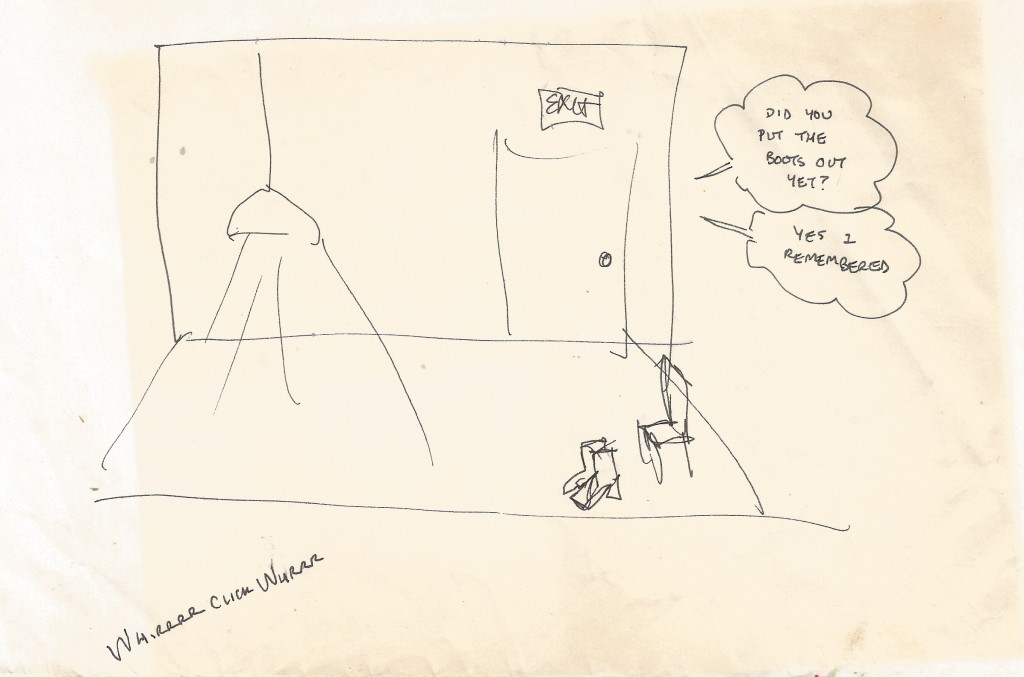

Here’s a sketch I doodled in my program of NHAT’s inaugural show, a 1986 “preview” workshop of Ann Wilson’s The Dream of Anna O, which Rush co-directed and co-starred in (as the psychiatric pioneer Josef Breuer, seen opposite Bonnie Stein as Anna in the photo above):

The piece was later expanded, sans Ann Wilson, into a full-length work titled Fragments of a Life.

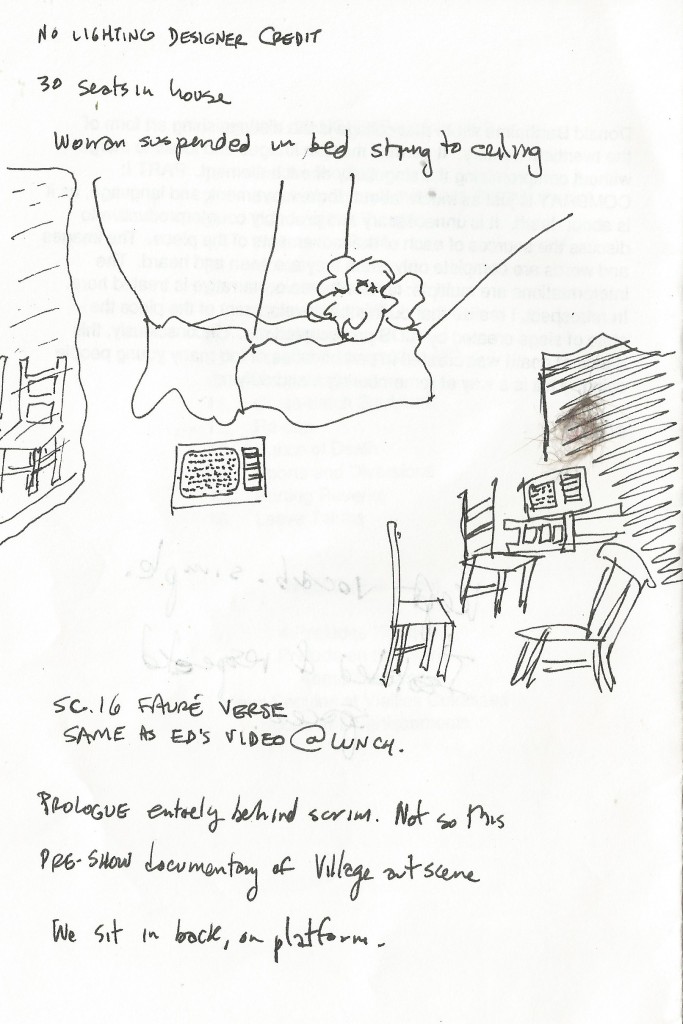

Here’s a similar sketch I did of the set design for the first part, “Combray,” of the multi-show “Proust Project: Remembrance of Things (Past) in the late ’80s:

Other NHAT productions included To the Mirrors, based on works by Jorge Luis Borges, and a piece inspired by the Samuel Beckett/Jasper Johns art collaboration Foirades/Fizzles.

But perhaps a better way to demonstrate Michael’s diverse cultural interests, and his need to let them all bounce off each other, is this set list from when he sang a concert of “Tenor Tunes” in the Park of the Arts behind the Arts Council building on Audubon Street in the New Haven “arts district” in 1987:

• “Sunday” from Sunday in the Park With George

• “Bring Him Home” from Les Miserables

• “At Night She Comes Home to Me” from the musical Baby

• The Eagles’ “Try and Love Again”

• “Fanny” from the musical Fanny

• “Jenny Rebecca” by Carol Hall

• Handel’s “Where Ere You Walk”

• The Randy Newman song “Old Man”

• “If We Were In Love” from the Luciano Pavarotti romcom Yes, Giorgio

• and two songs from Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd: “Pretty Women” and “Johanna.”

Michael and I had a good working relationship. I was one of the few theater critics in the area that would actually review his shows and not just run a photo in the “Best Bets” preview sections. NHAT fell into that abyss of small non-profit theaters that major papers would decline to review based on arbitrary policies about what they felt was commercial or professional or worthy of attention. Michael would agitate for more coverage of small theater—not just his own company, but the literally dozens of performing arts groups that were enjoying a renaissance in the city during the ‘90s. He would frequently acknowledge me by name when doing his introductory speeches at NHAT shows, and even nominated me for some arts awards. This could be both flattering and embarrassing for me, but I appreciated how much Michael and I shared an interest in spreading the word about small-scale, acquired-taste performances that were fully formed, carefully thought through and were being ghettoized as too “artsy” or “distant” when in fact they’d earned and deserved and a much larger audience.

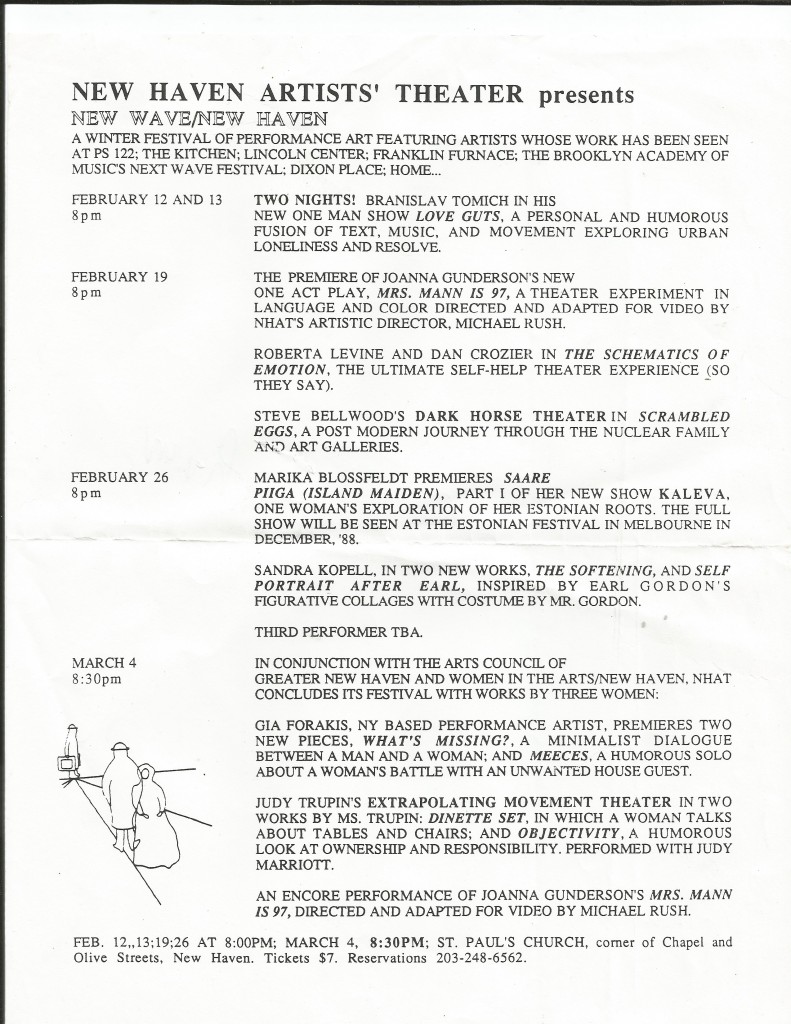

Michael didn’t just seek a greater understanding and awareness for his own work. He co-organized performance series that brought many worthwhile New York performance artists—including some great great ones, like Branislav Tomich and Dan Hurlin—to New Haven. He searched out like-minded arts communities and learned new techniques for engaging audiences. He sought out fellow performers from a wide range of disciplines, realizing that if he wanted to build a performance art community he’d have to lure people from the existing art, music and theater scenes, then create a comfortable new collaborative environment for them. You could liken this task to starting a new planet, populating it and tending its ecosystem. He was remarkably successful at it.

But beyond my admiration for his artistic accomplishments and our mutual desire to promote and publicize that work, I always found Michael Rush to be a great guy to talk to. We had a lot of tastes in common. We both worked both sides of the New Haven town/gown divide. We both had strong opinions that we tended to deliver calmly, without rancor or antagonist. Michael was one of those guys I was always happy to run into at an opening reception or cocktail party because I would be assured of a decent conversation.

His voice was so soothing, so non-confrontational, so lulling, that I once literally fell asleep while interviewing him. This was at a period of my life when I was working through some severe insomnia and staying awake for days at a time. Michael was amused and sympathetic watching my struggle to focus on our conversation and not pass out. We were able to laugh about the irony, since we were both so used to other people’s eyes glazing over when we talked about modern art and modern theater,

Reading the obituaries about Michael Rush, I realize how well-recognized he is in the art world and how his theater exploits are much lesser-known (if acknowledged at all). He made international headlines as the curator of the art gallery at Brandeis University, standing firm against trustees who wanted to sell off the school’s art treasures as a short-term budget-balancing fix. Michael won the battle but lost his job. Fortunately, his principled stand made him highly desirable to arts institutions which actually valued their holdings, and he landed a prestigious gig as the first director of the Eli & Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University in Lansing, Michigan.

I know Lansing a little. My parents were part of a summer stock theater a few miles from there, which (after we’d left) morphed into the well-known regional theater The Boar’s Head and moved to Lansing proper. It’s a region that has a deep appreciation for the arts but little patience for pretentious artiness. They’ll willingly try new works but they have to be marketed carefully. Michael seems to have grasped this intuitively, and the obituaries are full of praise for his accessibility and his careful approach when exposing museumgoers to provocative or progressive new art. It’s an attribute I’d come to associate with him during his New Haven years. Like all theater people, he wanted more people to see and appreciate his shows. Unlike a lot of them, he didn’t act lofty and pretentious about this, chastising audiences for not being able to understand what wonderful things he was doing. Both as a theater creator and (for only a handful of articles) a theater critic for the New Haven Register, he took the developing and preparing of audiences for new or difficult works as a challenge. He was gracious. He was understanding. He was soft-spoken and even-tempered, not bombastic or superior-sounding. He thanked people for coming. He held talkbacks and discussions. He believed in his heart that modern art was for everybody, not for the arbiters and elitists and the oneupmanshippers and the various other select few.

The art world knew Michael Rush as a disseminator, a popularizer, a sharer. New Haven theater folk knew him as an actor, director, conceptualizer and creator. In both realms he used his passion and intelligence to build new levels of appreciation, not rarefy and isolate them. A guy like that deserved to stay in the world a whole lot longer.

Permalink

A wonderful musing on a great guy, Chris. I still have vivid memories of Michael and of rehearsing The Dream of Anna O and “mastering” the butoh walk. A time in our lives I remember with great fondness…