You never monkey with the truth.

—Ben Bradlee, editor of the Washington Post

To hell with the truth! As the history of the world proves, the truth has no bearing on anything. It’s irrelevant and immaterial, as the lawyers say.

—Eugene O’Neill, The Iceman Cometh

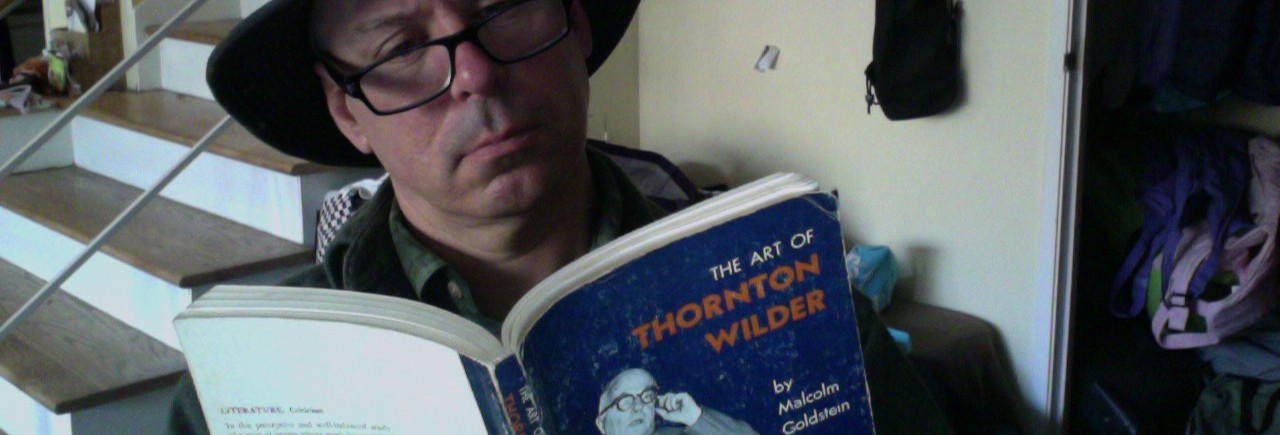

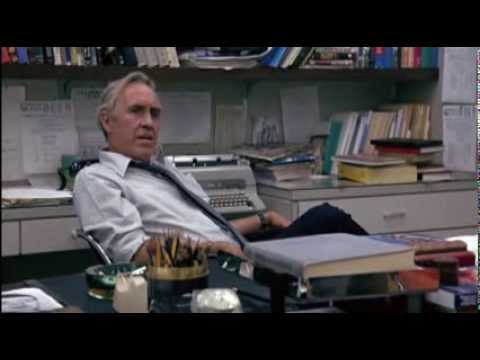

Ben Bradlee died, so Jason Robards is getting a lot of attention too. Robards played Bradlee in the film of All the President’s Men. Although he was Chicago-born and his career was New York-centric, Robards lived for years in Southport, Connecticut. I remember seeing him sitting peacefully in a corner of the Long Wharf Theatre Stage II lobby when a memorial event was held for longtime Long Wharf diva Joyce Ebert. (Ebert is honored in the current Long Wharf production of Our Town as one of the photo portraits resting on chairs in the Act 3 graveyard.)

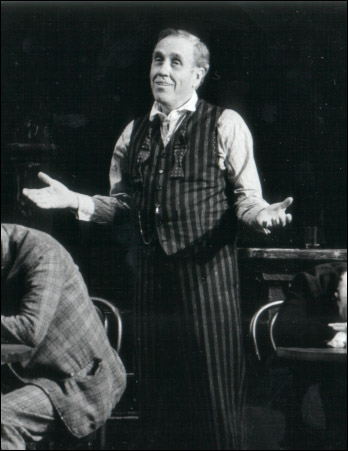

Robards was one of the greatest living interpreter of another Connecticut-related theater legend, Eugene O’Neill. He specialized in O’Neill plays which weren’t staged until after the playwright’s 1953 death.

Following his career-making turn as Hickey in the 1956 Off-Broadway revival of The Iceman Cometh, Robards originated the role of Jamie Tyrone in Long Day’s Journey Into Night, which had its pre-Broadway try-out at the Shubert in New Haven at the end of that same year. He played an older version of the Jamie character, James Tyrone Jr., in a revival A Moon for the Misbegotten in 1977. He played Hughie in 1964 and did A Touch of the Poet in 1977. He did Long Day’s Journey in New Haven again in 1988, playing the elder James Tyrone this time, in repertory with Ah! Wilderness, in which Robards played the twinkle-eyed grandfather. (The shows were a special collaboration between the Long Wharf and Yale Rep, marking the 100th anniversary of the

So was Ben Bradlee an O’Neill character? Jason Robards certainly played him as one, with the actor’s patented mix of fired-up and world-weary.

O’Neill wrote for The New London Telegraph in his youth, palled around with two of the great reporters of the early 20th century, John Reed and Louis Bryant, and made the father figure in Ah, Wilderness a newspaper editor. But he grew to severely distrust journalists. In the introduction to the collection Conversations With Eugene O’Neill, editor Mark W. Estrin explains that in the rare cases when O’Neill did give an interview in the later years of his career, he would avoid being quoted verbatim. Estrin elaborates:

Richard Watts, Jr., who interviewed O’Neill for the New York Herald Tribune, confronts the matter pointedly in his report of a conversation shortly before the opening of Mourning Becomes Electra. Though he never so states it directly, Watts is almost certainly reflecting O’nhill’s explicit refusal to be taken down verbatim, a desire Watts seems determined to honor in order to ensure future access. “It strikes me,” Watts writes, “that this report of Mr. O’Neill has, in its refusal to quote from its subject directly, something of the quality to be found in accounts of a vague and mysterious White House Spokesman.

So Eugene O’Neill knew something of plausible deniability and verbal politics.