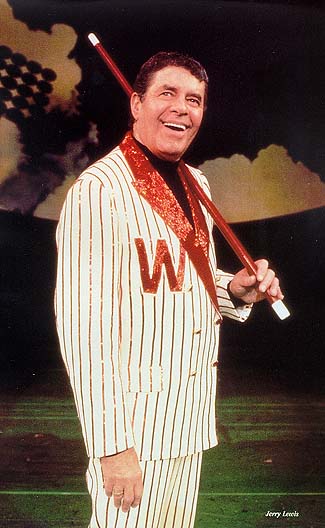

Jerry Lewis is up to his old tricks. You know, the cane-throwing trick. The glass in the mouth trick. And the withering glare and obnoxious comments which repel some of his greatest admirers.

Thanks to my old editor Josh Mamis for pointing out this VICE mag piece—Jerry Lewis is Still Alive (and Still a Piece of Shit)—and for adding this comment to its web manifestation:

This one’s for Christopher Arnott to relive his own memorable experience with Mr. Lewis.

It’s instructive, for some of the other comments on the article suggest that Lewis’ behavior at a recent live show is simply a type of “insult comedy” or “classic Rat Pack comedy” that is flying over the head of VICE’s young whippersnapper reporter.

In fact, I can attest that Jerry Lewis’ distasteful behavior is a longstanding part of his everyday persona and not some curmudgeon act put on for show. It’s not a comical character he puts on for public appearances. There are anecdotes out there about him turning on loyal staff, diehard fans and authorized biographers.

My own experience with Jerry Lewis was when he appeared in the national tour of the Broadway revival of Damn Yankees in 1995. He’d followed Victor Garber and Jonathan Hadary in the role of Applegate (i.e. The Devil) on Broadway, and was booked to star in the show on the road. Prior to its stop in New Haven at the Shubert Theater, I arranged to see the tour in Boston and interview Jerry Lewis there.

Like a lot of people who grew up in the ‘60s, I knew a lot about Jerry Lewis. Matinee screenings of his comedies were a Saturday movie-going ritual throughout my childhood. I was not only a lifelong fan of his but a big defender. I thought he’d been overlooked as a founder of the Rat Pack and in general given short shrift for his many achievements because he was a comedian and not a more “serious” movie star or pop crooner.

Prior to Damn Yankees, when Lewis had visited the Shubert with his one-man show (similar to the one VICE covered in its article) I’d done a cover story for the New Haven Advocate titled “Jerry Lewis is God,” itemizing the seven stages of his ascension to godhood. That the story was subtitled “Why has he forsaken us?” had now been tempered by his enthusiastic return to the live stage.

Lewis had started as a vaudeville performer, shifting to the newer area of nightclub comedy when he concocted a double act with Dean Martin. I don’t need to fill you in on Lewis’ illustrious career as a performer, director, producer, philanthropist, TV host, inventor and beyond, but it’s worth noting that in many interviews and autobiographical articles, a certain defensiveness shines through. He’s painfully aware, it seems, of not getting the credit as an innovator that he deserves. This sometimes translates as an unruly defiance, but really there’s some obvious insecurity, and genuine annoyance at the injustice, in his manner.

I thought I could talk with Jerry Lewis on his own terms and get the story I needed. So I went to Boston and sat through a Damn Yankees press conference with a bunch of other reporters. Lewis’ bravado was in full flower. The Nutty Professor remake had recently been announced, and someone asked Lewis what he thought of Eddie Murphy doing the role. “What do I think of it? I cast him,” Lewis replied, which would appear to be a massive overstatement. Certainly Lewis would have had to have signed off on the project, but based on his own statements about the remake years later, he had little to do with it and didn’t approve of the slant of much of its humor.

Press conference over, I waited for my private interview with Jerry Lewis. I was ushered into a fancy room. Jerry Lewis sat in a chair right in the middle of the space, and his publicist sat a few feet away for the entirety of our chat. (It is considered bad form for publicists to attend interviews, though some stars nonetheless insist on their talks being monitored. When publicists are present, they’re expected to not affect the conversation. This one jumped in multiple times.)

As I entered, I casually mentioned that I’d remembered Jerry Lewis performing in the very same theater we were now talking in, when he’d been doing the pre-Broadway try-outs of the revival of Hellzapoppin. The show had not lasted long in New York, but since it had been his last substantial stage production, decades before Damn Yankees, I didn’t have any problem bringing it up. Turns out I hadn’t been warned, as I later found out other writers had, not to mention Hellzapoppin in any way.

“I have no idea what you’re talking about,” Lewis said, with a serious face. He wasn’t saying it in jest. I repeated my statement, thinking maybe I’d mistaken the theater or something. But instead of correcting me or moving on, he continued to express ignorance instead. ““I have no idea what you’re talking about.” If he’d said, “Let’s not talk about that,” I would have understood. But “I have no idea what you’re talking about”? Just by not understanding why he was saying it, I got him to say it three times.

Not a great start for an interview, which quickly got worse when a succession of questions about his storied past fell on deaf ears. Literally, it was as if he didn’t hear the questions. He simply stared at me and didn’t respond. The silence was deafening.

Before I go on, I’ll just note that I’m not Oriana Fallaci or Bill O’Reilly, that these were not provocative questions, and that I was known to be an amiable and experienced interviewer or I wouldn’t have been there in the first place. (This was one of just two or three interviews Lewis did with the Connecticut media for that tour.) I’d done plenty of big-deal interviews with Broadway stars, and was used to being told “thank you for the good questions,” thanked for not wasting their time, praised for my special knowledge, etc. Some stars even called me back to continue chatting after our interview was done. I didn’t have insecurities about my ability to conduct interviews. But Jerry Lewis, with his stares and his silences, was really making me sweat.

So I buttered him up by asking him about his father, whom I knew from reading Lewis’ autobiographies that he had a great respect for. His answers, unfortunately parroted verbatim the stuff he’d already said in the press conference, and in his books. Mentioning the MDA telethon was an even deader end; “it’s all in the press packet,” I was told.

In a matter of minutes, I’d exhausted every avenue of conversation. And I wasn’t there to be a gushing fan. I needed some original quotes. A blank stare is not anything I could type up and punctuate.

So I went for it. “In your book, you do a whole chapter on The Day the Clown Cried…”

He blanched. I like to think Jerry Lewis blanched.

“…and you say,” I continued, “that it wasn’t released because of the financing.”

He seemed stunned that I’d even bring up the topic. I went on, demonstrating not just that I’d read his (then decades old) autobiography but that I’d apparently chosen to trust it, tossing his own tenuous justifications for shelving the picture back at him. I threw in some other bits which suggested I’d done my homework, respected his work in general, and wanted an answer to my question.

Then I threw his silent-stare thing back at him and waited for him to respond.

Finally he blurted out, “it wasn’t the financing.”

I took that as a minor victory, though at that point I was a puddle on the floor. My ten allotted minutes with Jerry Lewis was nearly up. I raced through a bunch of other longshot questions, thanked him and left the room. To be more accurate, I fled. The marketing director of the Shubert was in Boston as well for the press conference, and asked me how the interview had gone. I was literally shaking as I answered him.

It took a whole weekend of clubgoing with my friends in the Boston music scene to get over the horrors of those few minutes. (I’ll always be grateful to Jen Trynin for doing such a great set at a club on Lansdowne Street that I was able to stop thinking about my Jerry Lewis encounter for a minute.)

I wrote up my Jerry Lewis experience exactly as it happened, and there was quite a bit of discussion in the Advocate offices about what reaction we might expect from the Shubert or from the Lewis camp. At the Advocate at the time, provocations like this were commonplace, and there was no attempt to kill a story like this. But it made sense for editors to ask—for me to ask myself—if that was really the story I wanted to tell. It was. It ran, and there were no repercussions. I heard through grapevines that Jerry Lewis caused some consternation at the theaters where he played due to similar behavioral tics. My story may not have been the ideal promotional tool for the Shubert, but it was considered credible.

Part of me felt at the time that maybe I’d just been lucky all those years as an arts journalist, that many stars behaved this way, and that this was my baptism of sorts. But two decades later, I can say without reservation that I’ve never had an encounter that odd and unnerving in my professional life since.

I felt cowed, bullied, demeaned, ignored, repelled. And for what? For respecting an artist and wanting to preview his show? I have a lot of empathy for that scene of Jerry Lewis in The King of Comedy, being badgered for an autograph while he’s trying to use a public phone on a busy New York City street. But this wasn’t that. This was just what Jerry Lewis was like.

Permalink

Several years ago I became friends with a local man here in Boston who was a hard core autograph hound. He had autographs from as far back as Gary Cooper. He loved all celebrities and raved about how nice they all were. I once asked him there was anyone he didn’t like. “Only one. Jerry Lewis. He was a mean jerk”.