Looking through the press photo choices for the Yale Rep’s production of Arcadia, I was disappointed but not surprised to see that there were no pictures that showed off the grandiose scenic design by Adrian Martinez Frausto. My review in the New Haven Independent has points to make about that big-doored, big-windowed set, and also about how director James Bundy has used similar settings for some of his similarly formalistic and sedentary stagings of Wilde’s A Woman of No Importance and Albee’s A Delicate Balance. I had no clear photo image with which I could illustrate my point.

Last season, I actually emailed the Rep, annoyed that there were no photos of Fairytale Lives of Russian Girls which showed off its own elaborate set, one which involved pop-up hovels and a pit of fire. At my request, one was provided; I used it in my New Haven Independent review and noticed that it later turned up as a Rep poster.

I can mention similar incidents going back to the early 1990s when I felt that the photos I was being offered simply weren’t showing the show I was trying to write about.

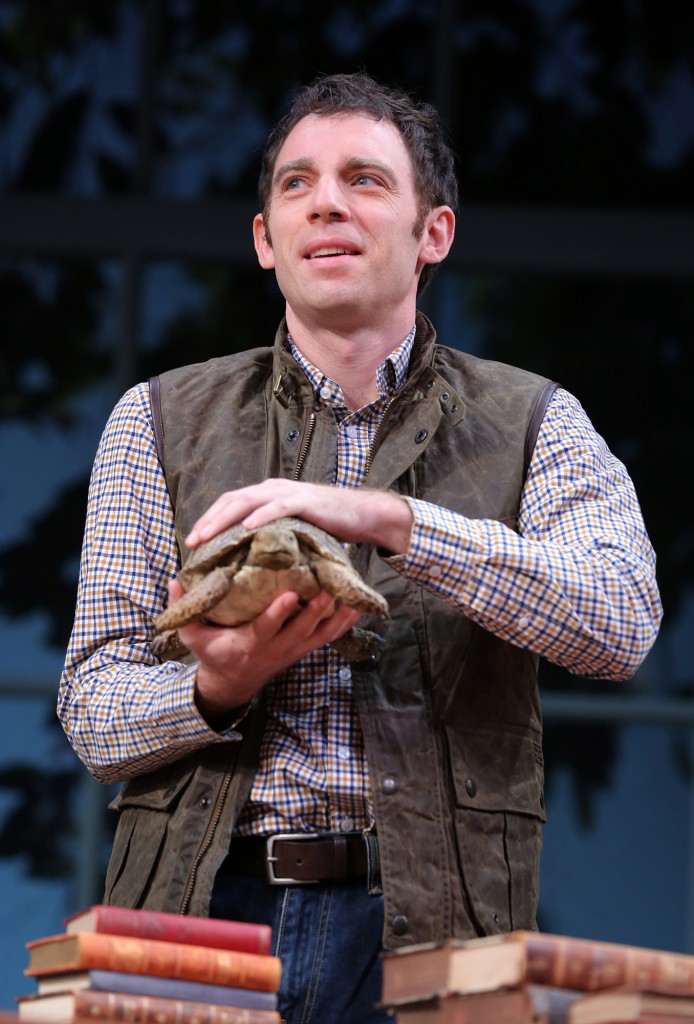

This really shouldn’t be such a regular problem. For each show it does in its regular season, the Rep sends the press a selection of over a dozen photos we are allowed to run with reviews, feature coverage, listings, whatever. With Arcadia, there are 16 images to choose from. Yet every one of them is middle-distance shot of either a single performer holding a prop (Rebeckah Brockman with a notepad; Max Gordon Moore with a tortoise; Tom Pecinka with a lit piece of paper) or two performers in a tight interaction (Brockman dancing with Pecinka; Rene Augesen glaring at Stephen Barker Turner). No extreme close-ups. More distressing to me, no tableau shots that demonstrate the scope of the show (Arcadia has a cast of 12) or its design.

In the case of Arcadia, a tableau shot seems a given. Every seen is set around the same huge table.

This, of course, has something to do with marketing. Print publications are running fewer photos of theater shows, and the ones they do run can be pretty small, so it behooves the theaters to pack as much visual information into a photo as possible. If a pic can suggest a deep dialogue or an action-packed scene, go for that.

Then there are the artistic gifts of the photographer to consider. For many years, the official documenter of Yale Rep shows has been Joan Marcus. She is a well-known New York theater photographer whose forte is the tightly framed, two-person caught-in-animated-conversation moment. I can always tell a Joan Marcus photo. She’s fond of outstretched arms, and when there isn’t such a gesturing limb to photograph, she likes clinches or side-by-side heart-to-heart chats.

Marcus is a master photographer, and I’m not trying to undercut her here. I’m just pointing out that it’s a disservice to the Yale Rep, and particularly to its designers, not to let a few of these photos give a sense of what the whole environment looks like. Anyone who knows the play Arcadia knows that it has one set, and that set could be considered a central character in the play. As Tom Stoppard puts it in his stage directions for Arcadia:

Something needs to be said about this. The action of the play shuttles back and forth between the early nineteenth century and the present day, always in this same room. Both periods must share the state of the room, without the additions or subtractions which would normally be expected. The general appearance of the room should offend neither period. In the case of props—books, paper, flowers, etc., there is no absolute need to remove the evidence of one period to make way for another. However, books, etc., used in both periods should exist in both old and new versions. The landscape outside, we are told, has undergone changes. Again, what we see should neither change nor contradict.

On the above principle, the ink and pens, etc., of the first scene can remain. Books and papers associated with Hannah’s research, in Scene Two, can have been on the table from the beginning of the play. And so on. During the course of the play the table collects this and that and where an object from one scene would be an anachronism in another (say a coffee mug) it is simply deemed to have become invisible. By the end of the play the table has collected an inventory of objects.

Now, having read that, and knowing how carefully the playwright himself has thought through the details of that room, don’t you want to see what that room looks like?

It’s enough to drive a Derbyshire real estate agent—or a long-suffering theater critic—nuts.