Ether Dome ended its season-opening run at Hartford Stage a few days ago. (I wrote both a preview and a review of the show for the Hartford Courant.) The history-based Elizabeth Egloff play now moves to Boston’s Huntington Theatre Company, where it will play Oct. 17 through Nov. 23.

There’ll be a slightly different supporting cast—local talent which don’t need to be given room and board are the life-blood of large-cast costume dramas such as this.

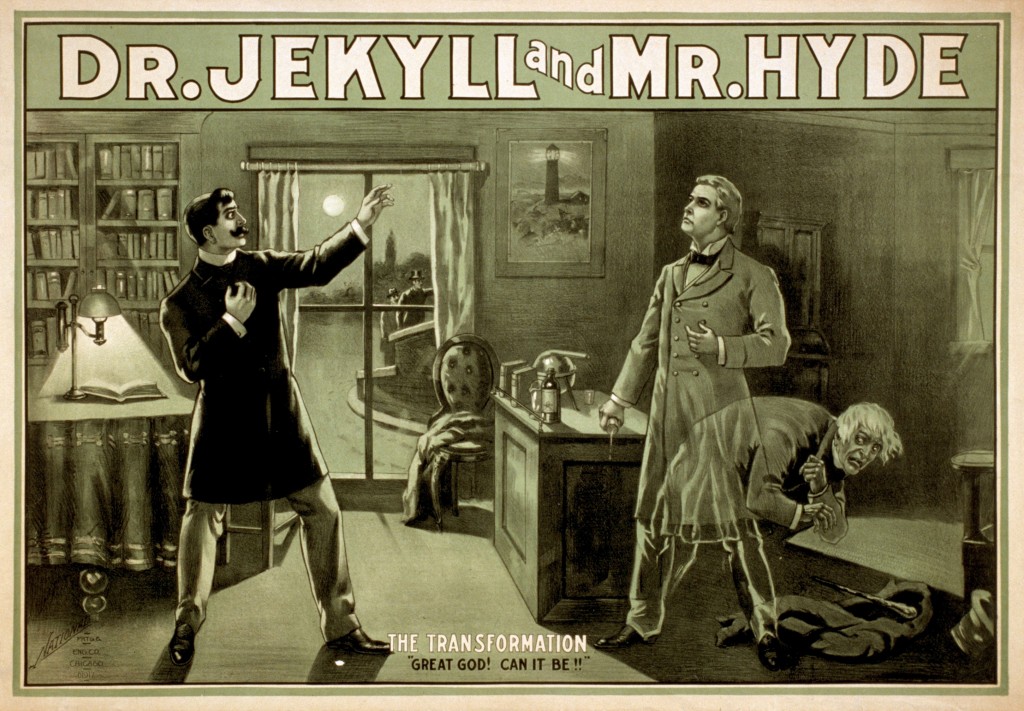

There’s another difference. Huntington has the show during Halloween, which might mean that folks make a little too much of a factoid that’s regularly made it into interviews and press releases about the show. To wit: that the play’s Hartford-based protagonist, Horace Wells, was an inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson psycho classic Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde.

Wells was a dentist who pioneered the use of laughing gas to prepare patients for painful surgery. His discoveries were taken away from him by a conniving, money-mad assistant. That’s what Elizabeth Egloff’s play is about. It’s also about the breakdown of patriarchal and status-based traditions in the medical profession. It’s also about adventure and discovery.

Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde isn’t actually mentioned in Ether Dome. The play has some blood and gore, and a grisly fall-from-grace, but it’s not fantastical or horrific. It turns some real-life people into composites, and collapses some time-frames to hasten the drama, but it’s not fiction. Its characters can show a callous lack of respect for each other, but there’s very little physical brutality. Besides, Stevenson’s story was written decades after the real-life events of Ether Dome, and have no bearing on it.

But the connection between Hartford’s own original anesthesiologist and Stevenson’s drug-taking doctor are irresistible, and you can’t blame Hartford Stage and the other theaters that’ve been hosting this massive co-production of Ether Dome for taking advantage.

That Wells/Jekyll theory, it turns out, is fairly recent. An episode of the Science Channel series Dark Matters: Twisted But True mentioned the doctors in the same breath in 2012. A 1991 Hartford Courant story about efforts to create a postage stamp in Wells’ honor mentions “There has been speculation that Wells was the inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson’s strange story of “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” published 37 years later.” Another Courant story on Wells, in 2004, said “Wells’ fall was so spectacular, sordid and mysterious that some historians speculate he was the inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”

But in Anne Rooney’s The Story of Medicine (1991), Horace Wells is merely listed as one in a series of doctors who became addicted to drugs (in this case chloroform) after using themselves as guinea pigs for medical experiments. One paragraph after she mentions Wells, Rooney writes “Charles Edouard Brown-Sequard only suffered disappointment when he injected himself with a fluid prepared from the testicles of guinea pigs and dogs in the vain hope that it would restore sexual potency. He was the inspiration for the fictional character of Dr. Jekyll (and his alter ego Mr. Hyde) and Serge Voronoff’s monkey-gland treatment.”

Somebody should write a play about that Brown-Sequard guy! (A musical, with dancing castrated dogs!)

Basically, Jekyll & Hyde has become an easy way to sell any show about a weird doctor. No shame in it. The story is also used to enliven lectures about medical history, such as this one at the University of Wyoming.

Last year, at the 19th Annual Spring Meeting of the Anesthesia History Association, held in Hartford, there was skepticism. According to a synopsis in the meeting’s program, there was a paper delivered by Rini A. Vyas and Sukumar P. Desai, M.D., on

“Horace Wells, Robert Louis Stevenson, Henry Jekyll, and Edward Hyde: Was RLS’

Masterpiece Inspired by Wells’ Tragedy?.” The authors say they “examined RLS’s letters, biographies, and other references in the literature, press, and online to determine whether any factual basis exists for RLS to be aware of Wells’ life, and also if it played any role in the creation of the plot of his famous novel.” Their stated results:

RLS was born in Scotland, after Wells had committed suicide at the Tombs, a notorious prison in New York. Coverage of Wells’ life and death received widespread coverage in northeastern United States, but there is no evidence that it was printed in newspapers or periodicals in England or Scotland.

RLS travelled widely, and spent many years in the US, mostly on the west coast,

far away from Connecticut. It is unlikely, that material related to Wells’ life was

published in local newspapers or magazines while RLS was in the US. There is

evidence to suggest that novelists of the period, psychologists, and the lay public

were quite interested in the concept of split personalities and the dual nature

of man. There is evidence that RLS dreamt about episodes similar to those depicted in his novel. All claims to any relationship between Wells and the novel

have come from the US, and none of them are backed up by evidence.

Which leads Vyas and Desai to this conclusion: “In the absence of evidence supporting a relationship between the behavior exhibited by Wells during the last few days of his life and any inspiration that RLS might have derived it, we conclude that there is insufficient evidence to suggest any relationship between them.”

Of course, if you’re an anesthesiologist, you might be happy to disavow any connection between your chosen profession and a murderous fictional fiend. Workers in blood banks must be sick to death of vampire jokes this time of year.

In any case, go see Ether Dome on its own merits. There are transformations in it, but not the “Eek! Ook! Ack!” potion-drinking Bugs Bunny kind. For those, you can see Jekyll & Hyde: The Musical, currently on its post-shortlived-Broadway-revival non-Equity national tour, 8 p.m. Oct. 11 at the Garde Arts Center in New London. A show which, I might point out, has nothing in its promo materials about 19th century Hartford dentistry.