I had the unusual, serendipitous experience tonight of seeing a bunch of middle school students perform a grown-up musical, then seeing a bunch of young adults create a play out of the fiction writings of an 11-year-old girl.

The grade-schoolers were trying to act twice their age, talking about marriage and gambling and psychology, though what shone through were the anxieties of youth. The college students (at the Yale Cabaret) were acting half their age, and what came out was bemused adulthood, a distanced appreciation of the mannerisms of children distilled by those who want to appear older and clearer-headed than all that.

Neither cast was able to act their scripts with what you might call realism. The point was to find a style that allowed them to get through it. Both did so admirably. But it’s funny to see two shows back-to-back in which age was such a compelling factor. Not the age of the characters—the age of the actors and of the writers. And it’s especially eye-opening in a week where I also saw Athol Fugard’s new play The Shadow of the Hummingbird, in which the octogenarian playwright is playing and chatting with a ten-year-old boy.

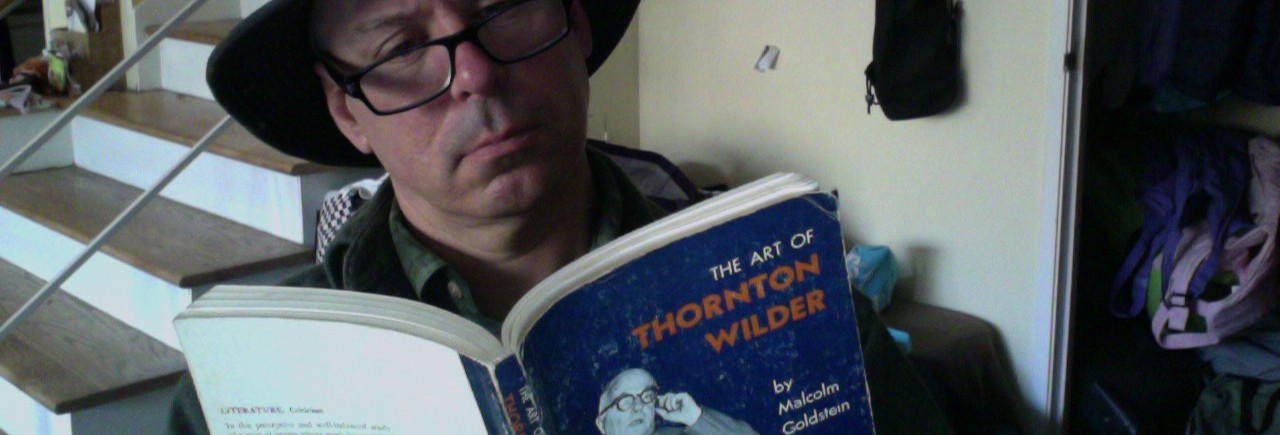

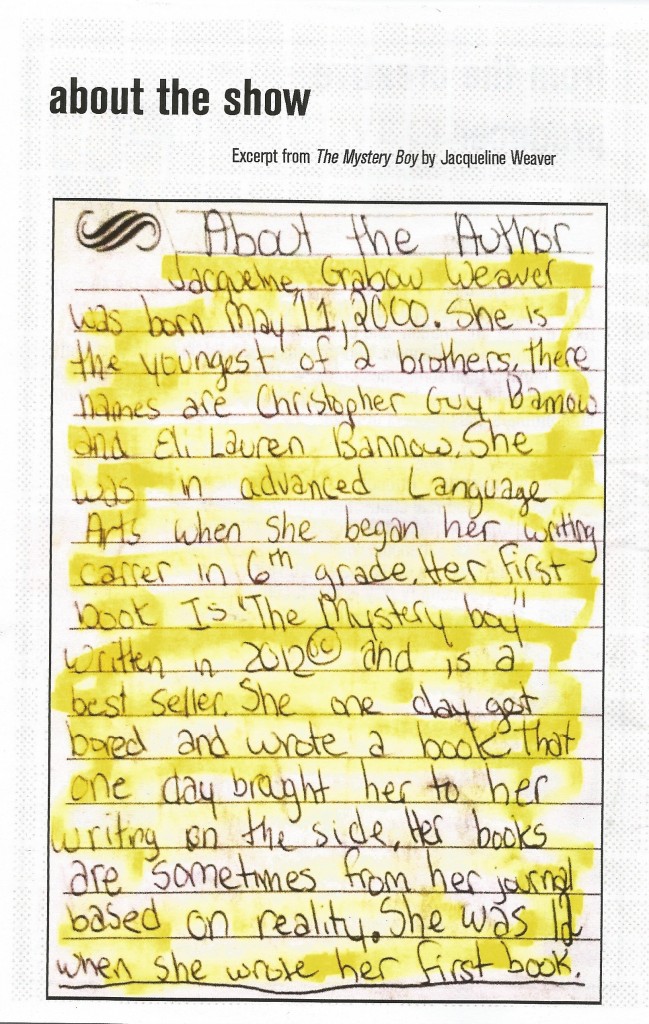

Now let’s concentrate on The Mystery Boy. It’s based on a 126-page handwritten manuscript written by Jacqueline Weaver when she was 11 years old. It was adapted and staged by her older brother Chris Bannow, who’s in his final year at the Yale School of Drama and who was a key member of last year’s Yale Summer Cabaret troupe. Two other members of that summer company, Ashton Heyl and Dustin Wills, figure prominently in The Mystery Boy’s ensemble cast. The other three actors are, to use the Cabaret lingo, “working outside their discipline”: one is a directing student (as is Dustin Wills), the other two are dramaturgs.

The show builds beautifully. The earliest chapters are read aloud, from a dogeared composition book, and only lightly staged. This gives you a sense of the style and of the thoughts-that-come-to-you-when-you’re-hanging-around-the-bedroom nature of the piece. By the end, though, the play has become a fast-paced, darkly lit, memorized and physicalized romantic adventure story. There are love triangles and supernatural threats and a raucous rendition of the pre-teen pop hit “I Am Your Gummy Bear.”

But as it progresses from gushing pre-teen crushes to vampire traumas, The Mystery Boy never loses the text style which, if you’re being charitable, retains the tones and inflections of tweens, but at the same time mocks it, providing so much comedy that there are loud whoops from the audience and regular points where the actors crack each other up.

The characters don’t say “I love you.” They say “I heart you.” Their inner monologues go like this: “I know, right? Why do I keep saying ‘right?’?!” A lot of the dialogue is in text-message code: “LOL,” “IDK and IDC,” “BF,” “BFF,” etc. That’s real enough, but the misspellings and mispronunciations and other mistakes of the young author are retained as well, which is amusing and endearing but not something I suspect a dramaturg or director would allow with writers of a different age. You’d simply change “exitment” to “excitement.” And maybe you’d try to present it in a voice that sounded less “Valley Girl.” OMG!