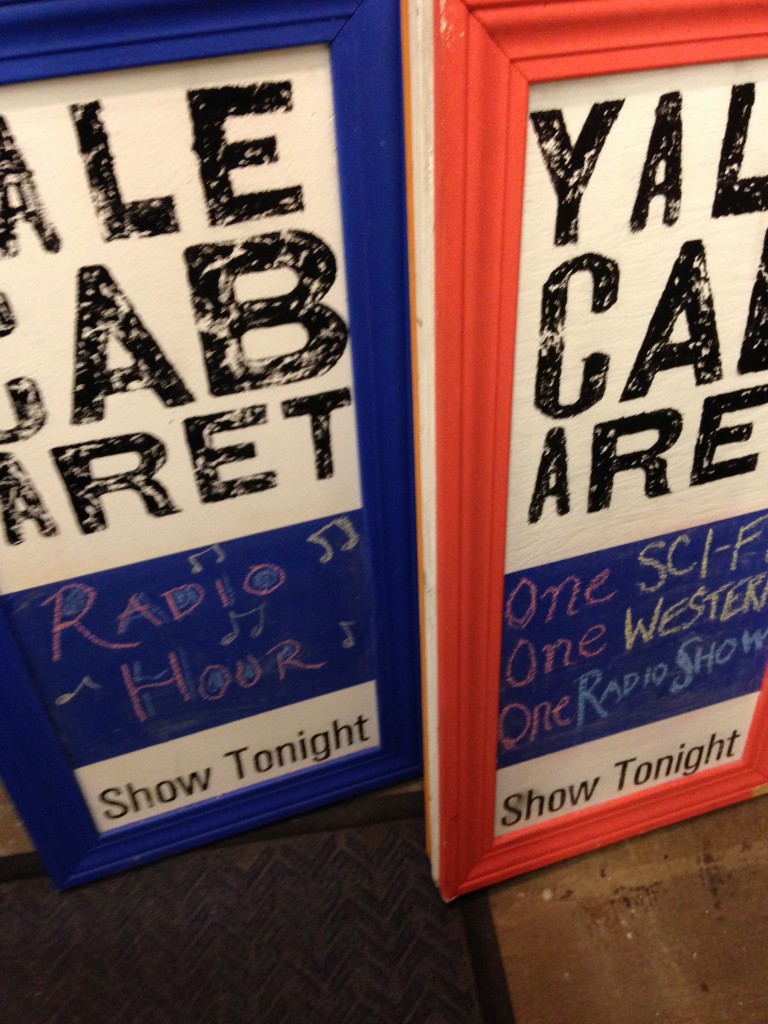

Radio Hour

Through November 2 at the Yale Cabaret, 217 Park Street, New Haven. (203) 432-1566, www.yalecabaret.org.

Directed by Paula Bennett. Dramaturg: Helen Jaksch. Scenic Designer: Reid Thompson. Costume Designer: Hunter Kaczorowski. Lighting Designer: Joey Moro. Sound Designer: Tyler Kieffer. Sound Designer/Composer: Steve Brush. Stage Manager: Kate Pincus. Technical Director: Rose Bochansky. Producer: Melissa Zimmerman. Cast: Prema Cruz, Ashton Heyl, Brendan Pelsue, Ariana Venturi, Tyler Kieffer. Musicians: Steve Brush, Tyler Kieffer, Jing Yin, David Perry.

Radio theater is about using your imagination. Right? Well, unless you already have tickets, odds are that you won’t be getting in to see (and hear) Radio Hour. The run has sold out, and there’s a lengthy waiting list. Radio listeners never had these troubles.

So let me tell you all about it. Are you sitting comfortably? Then let’s begin.

One of the first homegrown, out-of-the-black-box hits in the first few years of the long history of the Yale Cabaret was a musical revue called the 1940s Radio Hour. Conceived and directed by Walton Jones, 1940s Radio Hour really pulled off the hat trick of Cabaret immortality: it featured Meryl Streep in its cast, it transferred to Off Broadway, and it’s still being done by community theaters today.

When the Cabaret did 1940s Radio Hour, the golden age of live radio was only a generation old; the student cast was doing something their patents could fondly recall. The Cabaret’s done live radio style pieces in the decades since, from peppy recreations to darker concepts. A personal favorite was David Mamet’s the Water Engine, a play not written as a radio drama yet set in the 1930s, but which was staged in the classic live radio manner, to great dramatic effect.

These days, thanks to the internet and streaming radio, it’s easier to find and hear old time radio shows than ever. There are dozens of channels or apps airing such reruns; I’m partial to the Antioch Radio Network (http://radio.macinmind.com/), which tries to run old shows as close to the original airdate or time of year as possible.

Yes, it’s a nostalgia trip, but whereas once fans of this genre were stuck with only the best-known series, delivered two episodes at a time on LP or cassette, nowadays the variety and options are extraordinary.

What’s immediately noticeable about this weekend’s Radio Hour is that it has it has eschewed the golden age of the medium and takes its shows from the 1950s, when TV was already a threat. Where the 1940s Radio Hour dealt in WW2 patriotism and swing-band nostalgia, this Radio Hour evokes Cold War paranoia and the incipient days of Mad Men as radio commercial jingles get more complex.

The two main pieces in the show are “Zero Hour” by Ray Bradbury, who in the ’50s was an established fantasy talespinner whose work appeared regularly in magazines and had been adapted to film, TV and comic books, and “The Boughten Bride” episode from Gunsmoke, an iconic radio Western that made the successful move to television and became the longest running drama series of its time.

I’ve heard the original versions of both these shows, and have never heard them (or expected to hear them) in any other form. There’s a special thrill in experiencing a new theatrical interpretation of these familiar shows. The half dozen key actors (working with script in hand, in front of microphones that are there strictly for show) bring energy and intensity to the parts. They also bring a curious blend of insouciance and superiority, as if they don’t expect these words to stand on their own. And, you might wonder, do they behave as if they’re voice-only actors in a studio situation, or do they act out their characters with facial expressions and physical interplay? Inconsistently, they do both.

As tends to happen in these recreations, the sound effects specialists—Foley Artists, before that title meant much more technologically inclined sound design work—are given a prominent place onstage. Nothing wrong with that—fun to see horses or a storm come to life via coconuts or metal sheeting. In this case, the effects folk are also musicians, and it’s pleasant to hear a live rendition of the Gunsmoke theme, with the same actor who plays Matt Dillon, Aaron Profumo, playing the main melody on violin. As Dillon, Profumo doesn’t attempt to mimic the great William Conrad (future Rocky & Bullwinkle narrator and Ironsides star), who played the role for years on radio before the more telegenic James Arness took it over.

In fact, none of the actors here are borrowing much if anything from the shows’ original performers. They’re interpreting their parts their own way. Judging from how they crack each other up from time to time, you suspect some of them are switching to fresh voices for each performance.

The overlying conceit is that it’s Halloween night, and two popular fiction programs are playing back-to-back on the NBC network. There’s some serious dramatic license being taken there. In reality, these shows were broadcast on CBS, not NBC, and these specific episodes originally aired years apart from each other, and not on Halloween.

“Zero Hour,” adapted by Ray Bradbury from his own short story (published in the 1951 collection The Illustrated Man) was first heard on October 4, 1953 as an episode of Escape, then rerun in ’55 as part of a much more popular series, Suspense. Here, it’s presented as if it’s part of a science fiction anthology series—two of them, in fact. The staging begins with the spoken intro to “X Minus One,” a series which ran on NBC Radio from 1955-58, and closes with the reminder that “this has been Dimension X,” a whole different series which had a short life in 1950-51. (If you think that these sci-fi intros were swapped in because they’re more entertaining, you haven’t heard the ridiculous opening to Escape).

The Gunsmoke script, “The Boughten Bride” by that longrunning series’ co-creator John Meston, is from early in the first season, before Miss Kitty was a regular character. (There’s a woman named Big Kate to whom the marshall confides instead.) It first aired on July 12, 1952.

It’s hard not to think of some of these presentational choices as random or odd—attaching these shows to the wrong series or network or broadcast period. What’s worse is when this production kitsches up Zero Hour with a “far in the future—in the year 1985” gag and references to conversations on “televisors,” even though the original script is wisely and properly set at the time it was written, with the contemporary references to “Fifth Columnists” befitting its obvious Red Menace metaphors. A useful narrative voice, which adds to the suspense of the original, has been done away with completely in the Cabaret version.

As for Gunsmoke, it’s performed so that at several points one of the actors, Aaron Profumo is playing two roles, and basically holding a conversation with himself. Good for a laugh, sure, yet the drama here doesn’t really deserve to be deflected in this way. It’s a fairly compelling story of stage-robbing and kidnaping, with a surprise ending.

Not sure what’s the point of undercutting this material, especially when these are well-known, well-respected scripts. “Zero Hour” is an acknowledged Ray Bradbury classic, and many consider Gunsmoke to be the best radio series ever made. (The sound design on the original shows, with the everpresent chorus of neighing horses and bar-room banter is a most impressive bit of mood-setting that the Cabaret recreation does not begin to match). As you can imagine, if Radio Hour wanted to make fun of golden age radio, there are plenty of hokey, clichéd scripts to plunder.

Radio Hour also strives for a certain level of authenticity that doesn’t jibe with this satirical, light-comedy atmosphere. The studio set is austere. The costume design is authentic right down to the women’s opaque, seamed stockings. Ashton Heyl and Brendan Pelsue are particularly eerie, wearing 60-year-old fashions and hairstyles as if they always dress that way.

There certainly are strong points: the clever musical arrangements, the working clock on the back wall, the camaraderie of the cast, some interesting spatial relationships among the actors as the dramas get going. But overall, this is a production that simply doesn’t trust its source material, places too much importance on design, and lacks both consistency and historical accuracy.

Sorry to be a downer, but there are extraordinary connections to be drawn between old radio-studio-bound drama and the black-box theater process at the Yale Cabaret. Many previous radio-theater-style shows at this theater have demonstrated this. Radio Hour, while entertaining enough, just doesn’t tune in very strongly.