The Yale Cabaret has announced its spring 2013 line-up: Ten shows, each running for five public performances (and one audience limited to the playmakers’ Yale School of Drama classmates) plus one special work-in-progress event. As has been in the case in recent years at the 45-year-old student-run experimental drama venue, some are established scripts, others are brand new and the rest are somewhere in between, but nothing is as you’d see it anywhere else.

The comments here are based on my own researches. If I get a chance, I’ll chat up the Cabaret overseers sometime in the New Year for their own comments.

The special event comes first, on Jan. 8 at 8 & 10 p.m. with two open dress rehearsals of Hamlet, Prince of Grief, by Mohammad Charmsir, directed by Mohammad Aghebati and performed by Afshin Hashemi, prior to its run at the Public Theater’s Under the Radar Festival beginning the following week in NYC. The 30-minute one-man Farsi-language rendition of the Shakespeare play is accomplished with the puppet-like manipulation of “household objects and children’s toys.” A YouTube trailer for the show is here.

Jan. 17-19: All of What You Love and None of What You Hate. By Phillip Howze, directed by Kate Tarker. Howze is an African-American playwright and director who’s worked with theater artists in Burma, Turkey and the U.S. and is involved with the social justice arts organization freeDimensional. Kate Tarker’s a playwright herself as well as a director, who’s in the second year of her Yale School of Drama studies.

Jan. 24-26: The Island by Athol Fugard, John Kani and Winston Ntshona, directed by Kate Attwell. The great Fugard’s reputation in the U.S. was built upon memorable premieres of his works at Long Wharf Theatre and the Yale Rep, and augmented in recent years with premieres and revivals of a number of his plays helmed by Long Wharf artistic director Gordon Edelstein. The Island had its U.S. premiere at Long Wharf in 1974, alongside another Fugard one-act, Sizwe Banzi is Dead. The director of the Yale Cabaret revival is Kate Attwell, an open-minded theater artist whose prior Cabaret exploits include Hong Kong Dinosaur, Hundred Year Space Trip (in which she also performed) and (as a performer) Young Jean Lee’s Church.

Jan. 31-Feb. 2 and Feb. 7-9: The Cabaret is dark.

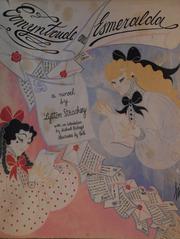

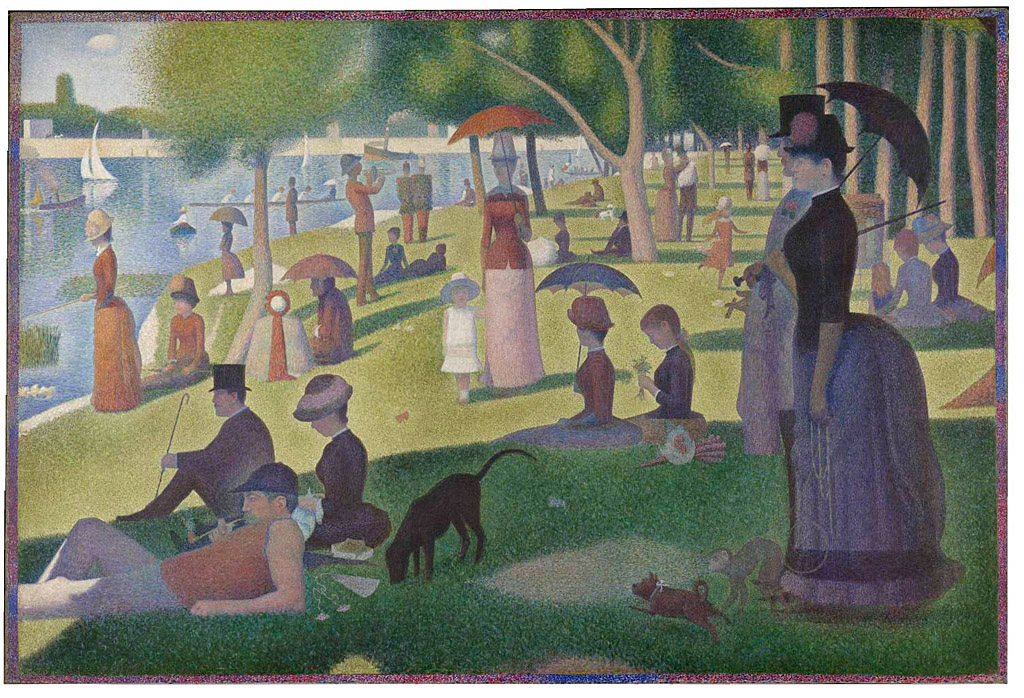

Feb. 14-16: Ermyntrude and Esmerelda: A Naughty Puppet Play, based on the Ermyntrude and Esmerelda: A Naughty Novella by Lytton Strachey, adapted and directed by Hunter Kaczorowski. Giles Lytton Strachey was a seminal member of the Bloomsbury Group and is best known as a biographer, but like his Bloomsbury comrades he dabbled in many arts. This social satire, written in 1913 but not published until 56 years later, is amusingly described by www.glbtq.com as “a semipornographic epistolary novel written as an exchange of letters between two naive seventeen-year-old girls, is a send-up of, among other matters, sodomy among the middle classes.” Director/adapator Hunter Kaczorowski just did the costumes for Ethan Heard’s Yale School of Drama thesis production of Sunday in the Park With George.

Feb. 21-23: Halfway House, created by Jackson Moran. No info on the piece, but Moran (who’s also an actor) directed the triumphant Yale Cabaret production of Sam Shepard’s Cowboy Mouth in late October.

Feb. 28 through March 2: The Bird Bath, created by its ensemble cast and directed by Monique Barbee. Another original piece. Barbee was a regular presence at the Yale Cabaret last year, in several school-year shows (including Persona and Chamber Music) and the one-person storytelling saga The K of D during the 2012 Yale Summer Cabaret season. She was one of the people enlisted to o White Rabbit, Red Rabbit at the Cabaret this season, and just played Dot in Sunday in the Park With George at the Yale School of Drama, from which she graduates next spring. Comfortable with both ensembles and solo projects, it’s nice to have her back in the Cabaret.

March 7-9: The Small Things, by Enda Walsh, directed by Emily Reilly. The Ireland-born, England-residing playwright’s disorienting and ultimately horrifying pair of interwoven monologues has, due to its themes and fantastical leanings, sometimes been compared to Caryl Churchill’s play Far Away, which the Yale Cabaret presented a couple of years back. Emily Reilly was the dramaturg for and a supporting player in Alexandru Mihail’s immaculate adaptation of Ingmar Bergman’s Persona at the Cabaret last year, and also appeared as an actress there in Trannequin!,

March 14-16: Lindbergh’s Flight, by Bertolt Brecht. No director is mentioned, and there’ll probably have to be a musical director besides. Known by two different German titles—Der Ozeanflug and Der Lindberghflug—and several English ones (The Flight Across the Ocean), it was written in 1929 as a radio play with music and was scored by Brecht’s frequent collaborator (and established composer of works for radio) Kurt Weill, with some numbers contributed by Paul Hindemith, who later became a legendary professor of music at Yale. Hindemith’s contributions were later replaced with more by Weill. Even later, when the famed transatlantic traveler revealed himself as a Nazi symphathizer, Charles Lindbergh’s name was dropped from the piece. Sections of the piece can be found here. This is hands-down the Cabaret show this semester which I am most excited about, sight unseen and creative team unknown.

March 21-23: The Cabaret is dark. Recovering from the Brecht, no doubt.

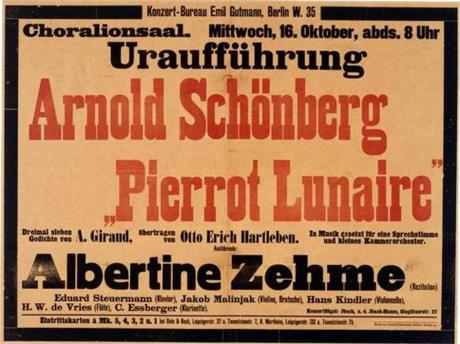

March 28-30: Pierrot Lunaire, based on Arnold Schoenberg’s Dreimal sieven Gedichte aus Albert Giraud’s ‘Pierrot lunaire’, staged by Ethan Heard. Hot on the heels of a Kurt Weill presentation is one by that composer’s contemporary, Arnold Schönberg, who set 21 poems by the symbolist poet Giraud (translated into German by Otto Hartleben) to music, with vocals in the Sprechstimme (speak-singing) style. The work, which turned 100 years old this year, is famously jarring and polarizing.

April 4-6: The Twins Would Like to Say, by Seth Bockley and Devon de Mayo, directed by Whitney Dibo and Lauren Dubowski. Bockley’s based in Chicago, but I known in New Haven for the script he wrote for the Gabriel Kahane-composed musical February House at the Long Wharf Theatre last year. Bockley works at the Goodman theater, and his co-writer here, Devon de Mayo, was the director of Chicago’s Dog & Pony Theatre Company, which specializes in new works. De Mayo’s play As Told by the Vivian Girls was developed at Dog & Pony, as was this one, The Twins Would Like to Say. It was produced in 2010 at Steppenwolf’s rather Cabaret-esque Garage space. It’s based on the true-life pact between identical twin sisters: that they would not talk to adults and agree to do everything in unison. Whitney Dibo and Lauren Dubowski were the driving forces behind the Cabaret’s reworking of Jacob Gordin’s The Yiddish King Lear last year. Like the playwrights, Dibo’s worked in theater in Chicago. This past fall, Dubowski developed the Cabaret’s “rockabilly exploration of death” Ain’t Gonna Make It.

April 11-13: The Ugly One (Der Hassliche), by Marius von Mayenburg, directed by Cole Lewis. Von Mayenburg is a 40-year-old German playwright who’s got over a dozen produced plays to his name. This one was done at London’s Royal Court Theater in 2007, was done in Canada in 2011 (video trailer is here) and only just had its New York premiere in February of this year. It’s a dark comedy with a four-person, multi-character cast, about an unattractive man who gets cosmetic surgery but finds that his beautiful new looks carry their own consequences. Cole Lewis is in the directing program at Yale School of Drama, where she was Assistant Director for Will Eno’s The Realistic Joneses at the Yale Rep. She worked with Lauren Dubowski, Nicholas Hussong and other on Ain’t Gonna Make It at the Cabaret earlier this year.

The current Yale Cabaret staff consists of Ethan Heard (Artistic Director), Jonathan Wemette (Managing Director), Benjamin Fainstein (Associate Artistic Director), Nicholas Hussong (Associate Artistic Director), Barabara Ran-Tiongco (Production Supervisor) and Stephanie Rolland (Cabaret Assistant). The Board of Artistic Associates includes Margot Bordelon (directing), Lauren Dubowski (dramaturgy), Theodore Griffith (technical design & production), Alyssa Howard (stage management), Martha Kaufman (playwriting), Jennifer Lagundino (theater management), Jack Moran (acting), Matt Otto (sound design) and Masha Tsimring (design).

The Yale Cabaret operates out of a basement space at 217 Park St., New Haven. Food and drink are served before performances, which are at 8 on Thursday and 8 & 11 p.m. on Friday and Saturday. Tickets are $15, $10 for students. A 9-ticket flex pass is $70, $50 for students. Group rates are available. http://yalecabaret.org/