Sunday in the Park With George

Through Dec. 20 at the Yale University Theater, 222 York St., New Haven. (203) 432-1234.

Directed by Ethan Heard. Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim. Book by James Lapine. Musical Director/Conductor/Orchestrator: Daniel Schlosberg. Scenic designer: Reid Thompson Costume designer: Hunter Kaczorowski. Lighting designer: Oliver Wason. Sound designer: Keri Klick. Projection designer: Nicholas Hussong. Production dramaturg: Dana Tanner-Kennedy. Stage manager: Hannah Sullivan. Performers: Mitchell Winter (Georges/George), Monique Bernadette Barbee (Dot/Marie), Carmen Zilles (Old Lady/Blair Daniels), Carly Zien (Nurse/Mrs./Harriet Pawling), Jackson Moran (Franz/Dennis), Max Roll (Jules/Bob Greenberg), Ashton Heyl (Yvonne/Naomi Eisen), Jeremy Lloyd (Louis/Lee Randolph), Dan O’Brien (Soldier/Alex), Robert Grant (Boatman/Charles Redmond), Matt McCollum (Mr./Billy Webster), Sophie von Haselberg (Frieda/Betty), Marissa Neitling (Celeste #2, Elaine), Catherine Chiocchi (Louise/Waitress) and Mariko Nakasone (Celeste 1/Photographer).

It’s rare that you see a Yale School of Drama that looks and behaves so much like a Yale Dramat spring musical.

Don’t misunderstand—by comparing a graduate school work to an undergraduate one, I intend no disrespect, no charge of amateurism. The Yale Dramat hires professional directors and designers for its musicals, and draws exceptional student talent to perform in them.

But what those shows tend to lack is soul. With rare exceptions, they are generally built from templates, skewing to how the best-known (read: Broadway) productions of those shows are known to have worked. Already subject to the pacing and tonal demands set by songs and a score, such shows tend not to color far outside the lines.

That same sensation of color-by-numbers is what you get from Ethan Heard’s production of Sunday in the Park With George, which closes tonight at the Yale University Theater. (That venue, as it happens, has been the accustomed stomping grounds of the Dramat for a century or so, and the Dramat has produced most of the Sondheim musical canon there, some of the shows several different times.)

The show is efficiently and effectively staged. For a musical produced by a drama school that has no specific musical theater training program, the singing is much better than audiences have any right to expect. The performances rise to the level of good regional theater, and make use of better resources. But it’s hard to see these students, all of whom have done sterling work in more freewheeling environments, holding back here.

Granted, that’s what James Lapine and Stephen Sondheim’s musical does in the first place. It constrains and conscripts and ultimately confounds.

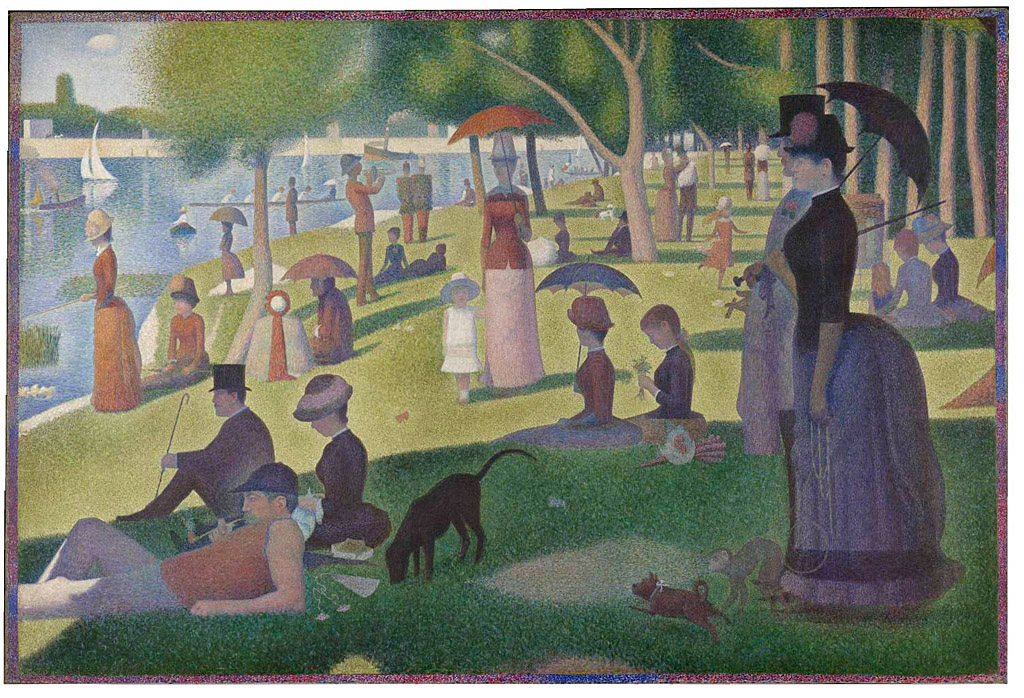

In Sunday in the Park With George, identities and backstories are created for everybody inhabiting Georges Seurat’s most famous painting, Un dimanche après-midi à l’Île de la Grande Jatte. On one level, I guess you could say this enlivens the painting. On another, it inhibits it, imposing a fixed interpretations on it.

I have a personal distaste for works which claim that artistic inspiration springs from real-world precedents and downplays the power of imagination. In film, that ignoble subgenre would include Shakespeare in Love and Becoming Jane. On the stage, that sort of literalism is found in Doug Wright’s Quills and Tom Stoppard’s After Magritte. Then there are the many productions which assume that the playwright has personally lived the work he is dramatizing. (New Haven audiences saw that in Gordon Edelstein’s direction of Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie at Long Wharf, which had Patch Darrah looking like Williams and shadowing the other characters spectrally.)

Beyond the audacity of assuming artists can based their art only on experiences they personally observed, I think Sondheim and Lapine did a better job of fleshing out another artist’s creations in their Grimmly amusing fairy tale deconstruction Into the Woods, and (with book-writer George Furth rather than Lapine), Sondheim had much stronger points to make about artistic fame and friendship in his musical adaptation of the Kaufman & Hart play Merrily We Roll Along.

Sunday in the Park With George is a set piece about art and society, and boy is it set. Its depiction of the smarmy New York art world of the 1980s is more outdated than its stuffy take on France in the 1890s.

Sondheim and Lapine have at least chosen the right subject for their show: The French painter Georges Seurat had a pronounced a scientific bent as he did an artistic one. He developed theories of, as the song goes, “Color and Light” which translate neatly to stagecraft. There’s good reason to explore what was aesthetic and what was scientific or realistic in his work. But the musical chooses instead to delve into a less substantial “what is art?” question when it reduces the idea of artistic fame to how much one accomplishes in one’s lifetime and who one needs to be nice to in order to get noticed. The musical’s second act posits that the baby in the painting is Seurat’s illegitimate daughter, then shows her nearly a century later (in the 1980s, when the musical was written), doting on her grandson, who has become a famous artist himself and whose newfangled NASA-level artworks/inventions are getting grants and acclaim because he’s mastered the art of schmoozing at fancy parties.

You could say that portraying self-involved, anti-social characters, often ill-mannered artists such as Georges and his grandson George, and the exemplifying of paintings that hang in galleries, necessitates some distance and restraint, a cool voyeurism.

Still, for a show about the vibrant life which exists behind such art, there’s altogether too much distancing here. Mitchell Winter sings both Georges elegantly, but he plays them gloomily and inwardly, focusing on the artworks he’s creating with such intensity that it’s not that different an expression from the disdainful tone he uses with family members, lovers and passersby. Where’s the spark, the passion? Without a few glimmers of excitement over his work, he’s simply a misanthrope. Winter nails the tricky pacing of Sondheim’s lyrics (which develop a musical equivalent of pointillist painting with short, staccato expressions), but when he should be exulting in his sung soliloquoies, he sounds instead like he’s lecturing the unappreciative—and he does enough of that already.

As Georges Seurat’s somewhat-muse Dot (one of several pointillism puns in the show—a dog is similarly named Spot), Monique Bernadette Barbee is corseted both literally and figuratively. In the first act she must maneuver a bustle, and in the second (as Dot’s grandmother) a wheelchair. In shows at the Yale Cabaret and Yale Summer Cabaret in the past couple of years, I’ve seen Barbee exhibit the most extraordinary range, from earthy contemporary wall-breaking solo turns to clinical, filmic, expressionistic ensemble work. This is the first time I’ve seen her so repressed. The only moment when her character truly became alive for me when I saw the show on Tuesday night was Barbee was the victim of a wardrobe malfunction (unlike Janet Jackson, she couldn’t get back INTO her dress) and vamped some squeals and giggles while the onstage dressers untangled her and buttoned her up.

This show is always cast based on the ability of the actors to resemble iconic figures in a world-famous painting. More intriguing casting choices can’t really be made. Most members of the cast have to hang back patiently (sitting on the sidelines at the sides of the stage, a la Chicago or the Doonesbury musical or, most pointedly, Our Town) and look like they’re more interested in the goings-on than they probably are.

Ethan Heard’s staging ideas, and his creative team’s design concepts don’t precisely duplicate the original New York production, or other well-known renditions of the show, but they’re very much in the same ballpark. Act One is all about the creation of a tableaux vivant of Seurat’s masterpiece Un dimanche après-midi à l’Île de la Grande Jatte, so you can’t expect much variation there. It does help that the Yale School of Drama has a program for Projection Design; Nicholas Hussong creates some fine effects to blend in with Reid Thompson’s set and Oliver Wason’s lighting, not to mention the actors.

In Act Two, instead of propping up cardboard figures of himself to decoy schmoozers at an art opening, the 20th-century George now has his forced-smiling image deployed on dangling TV screens. Heard, who has directed baroque operas starring Yale undergrads, and who was a Whiffenpoof in his own undergrad days (I also recall him vividly as a dancing journalist in a Yale Dramat production of Floyd Collins nearly a decade ago) certainly has a way with orderliness and mannered, prim presentations. But at key moments in the drama, chaos must ensue, and it simply doesn’t. It’s the most mannered chaos imaginable. Way too much uniformity and control. I waited in vain for actors besides Barbee to have problems with their costumes.

As for those costumes, there’s also an awkward “dress-up” quality to the production, since none of the actors are convincingly evoking the ages of the characters they are portraying, That’s a given in college musical productions, unless you’re doing West Side Story or Spring Awakening or Rent. And it may even be a directorial concept here, letting costume designer Hunter Kaczorowski’s immaculate and elaborate outfits set the characters’ demeanors rather than accents or gestures. But when the performers are already hindered in their expressiveness, layers and layers of clothing doesn’t help.

I expect more from the Yale School of Drama. I expect grand new ideas, and risks, and overreaching in order to learn, and student directors and designers taking full advantage of the largest production budgets they may ever be granted again. The only outré element of this whole production is music director Daniel Schlosberg’s new arrangements of the score for a 10-piece ensemble that’s heavy on wind instruments and doesn’t overwhelm with keyboards the way so many scaled-down musical theater orchestras do. Schlosberg and Heard worked together at the Yale Cabaret last year on a powerful song cycle entitled Basement Hades, and the composer has distinguished himself with his eclecticism and experimentation. I think that even the gifts of Daniel Schlosberg have been underrepresented here.

I certainly wasn’t crazy about this semester’s other Yale School of Drama show, Jack Tamburri’s Greek drama adaptation Iphigenia Among the Stars, but at least it wasn’t afraid to think big and fail big. There was much more to recommend it (and frankly much more to energize the actors) than I found in this studied, pristine, overprepared Sunday in the Park With George. And I’m certainly not down on the Yale School of Drama attempting musicals—Eleanor Holdridge’s exhilirating production of Brecht & Weill’s Happy End was one of my favorite YSD productions ever, and for all its structural flaws Michael McQuilken’s original rock musical Jib a couple of years ago still resonates strongly for me, and challenged its actors and designers on every level. This, by contrast, has an irritating confidence that comes from following rules, not breaking them.

If you’ve never seen a decent production of Sunday in the Park With George before, here it is. If that sounds like damning with faint praise, well, dot’s all, folks.

Chris,

Some of your critique is on the money, particularly re: Mitchell Winter (“when he should be exulting in his sung soliloquoies, he sounds instead like he’s lecturing the unappreciative,”) and I must say when I saw the show I thought the timing of the singing (not to mention pitch) was too often way off. But I can’t help but think that one problem you had with the production is that you just don’t like the show very much, which is unfair, in a way, to dump on Heard.

As you know, I am a big fan of the show. The score is delicate and haunting, among the most beautiful in musical theater — and in tune (pardon the pun) with its subject, something disproportionately lacking in most contemporary musicals with high ambitions (Pop comes to mind, and February House).

So, given your disdain for SitPwG, I think you do Heard a disservice. There were elements of his vision that I found inventive. The rake as canvas was a nice touch, for example, and the open set, with the stage hands visible as they worked the backdrops, was somehow warming and inviting, among a few other minor touches that I appreciated.

This is a really tough show to pull off. Georges is all internal — and if you don’t bring a certain vitality to the characters the show easily falls flat.

That said, I saw the Broadway revival a few years back, in a heralded transfer from the West End, and that production was all tech and no humanity, with near affectless acting, and really self-conscious use of projections. I’d go see Yale’s again over that travesty any day — all while waiting for a great, truly inspired production to come along. I wish Heard had figured out a way to mount it at the Cabaret (where I saw the single best production of Assassins ever) instead, but I’ll take what I can get.

Very neat post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Its not my first time to visit this website, i am browsing this site dailly

and get good data from here daily.