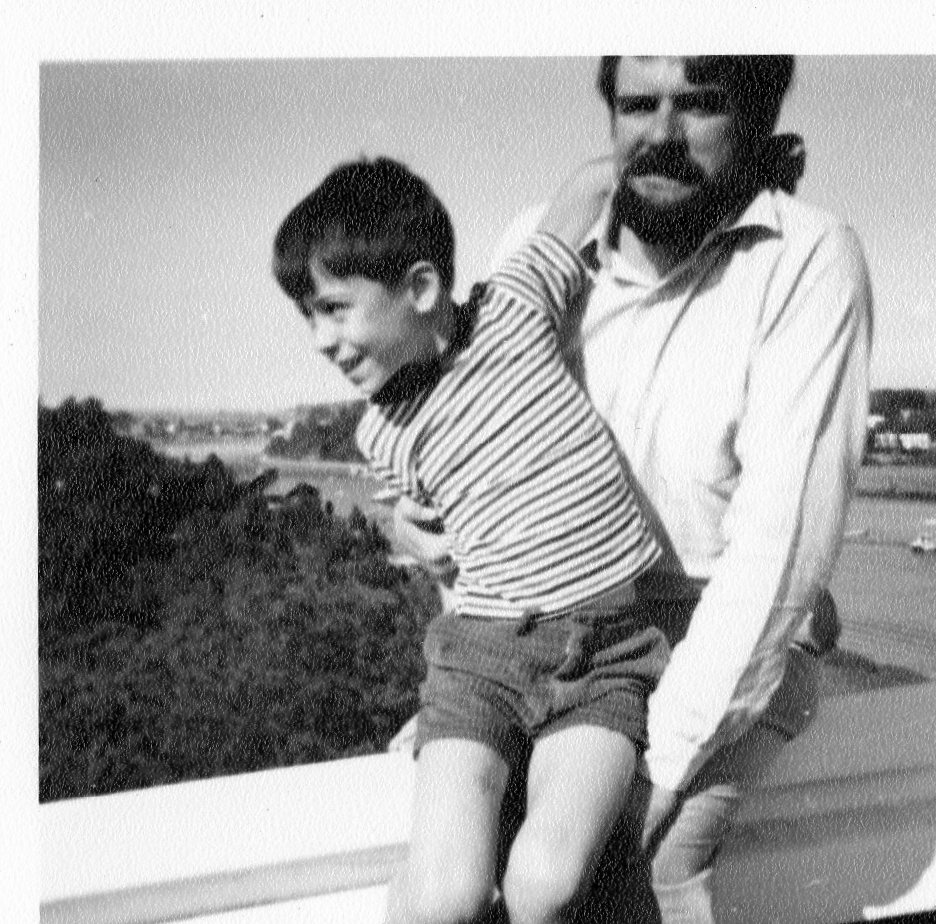

In the previous post, I mentioned my father, Peter D. Arnott. As it happens, today is the 22nd anniversary of his death, from stomach cancer in 1990. Had he lived, he would be turning 81 a few weeks from now on November 21st.

My father was born in Ipswich, England, and in his teen years devised a portable marionette theater with which he singlehandedly performed such classic plays as Doctor Faustus, Scapin, Oedipus Rex and The Clouds. He continued to adapt great dramas for his marionette theater for the rest of his career, touring internationally.

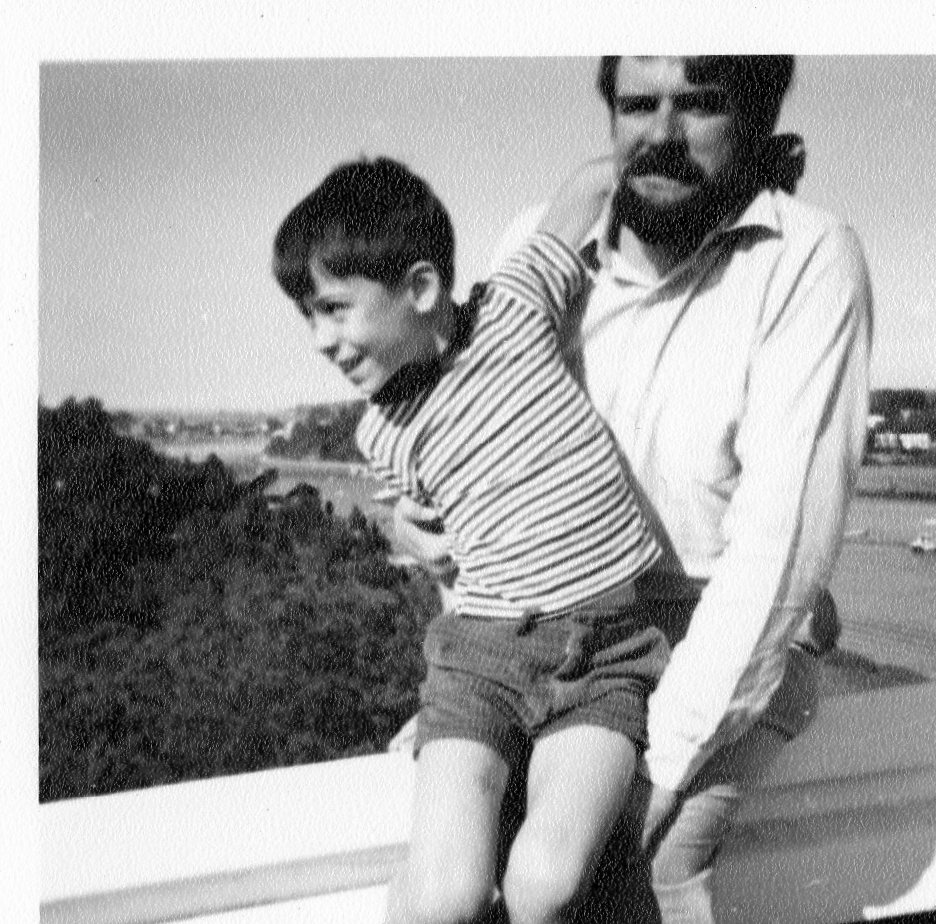

He was the first person in his family to go to college. He attended Oxford University and got his PhD at the University of Wales, which is where he met my mother. Since my parents were looking to settle in the United States, my father joined the Classics department at the University of Iowa. There, he directed a production of Aristophanes’ The Frogs that was so impressive he was asked to move over to the Theater department. During this time (when I was aged three to seven), my father became a partner in the Ledges Playhouse, a summer stock theater in Grand Ledge Michigan. The acting ensemble there included William Hurt, Mary Beth Supinger (later Mary Beth Hurt), Dennis Lipscomb and a host of other performers who would later become stars.

In 1969 my father was offered a position at Tufts University, where he taught for the next three decades, serving as chairman of the Drama Department for seven of those years. He taught several classes each semester, directed at least one student production a year and oversaw the professional company which presented summer seasons at the Tufts Arena Theater. Students at Tufts during his time included Oliver Platt, Hank Azaria, Jonathan Hadary, the founders of the avant-garde Double Edge Theatre and a face familiar to present-day New Haven theatergoers, James Andreassi of Elm Shakespeare Company. I have run into literally dozens (perhaps even hundreds) of students of my father’s over the years who have maintained steady careers in the professional theater—a remarkable percentage for any undergraduate theater program.

My father toured internationally with his puppets and directed some dazzling productions with live actors, but left an even greater legacy as a writer. He penned influential books on puppetry (Plays Without People), ancient civilizations (Introduction to the Greek World, The Byzantines and Their World, etc. etc.), and the history of theater in Japan, France, Greece, Rome and elsewhere. He penned a novel about Moliere. He wrote the standard textbook The Theater in Its Time and co-edited (with Otto Reinert) the respected anthologies Thirteen Plays and Twenty-Three Plays.

Oh, and he did about a billion other noteworthy things. He had a model railroad lay-out that filled the third floor of our house and is now ensconced in a museum in Wenham, Massachusetts. (When other universities, including Yale, tried to coax him away from Tufts, the sticking point was always that moving would mean having to dismantle the model railroad.) He was a fine photographer. He spoke seven languages. He loved to take our dogs on long walks. He would indulge my sisters and I in our countless hobbies, from stargazing and birdwatching to exploring cemeteries to sailing and horseback riding.

When I developed my own interests in theater, I deliberately chose criticism and arts journalism as my main endeavors so that I wouldn’t have to compete with my father on his own turf. I attended Tufts and audited countless theater courses and seminars but majored in English to give me some distance. As it was, there was one year where I directed a production of the Kaufman & Connelly comedy Beggar on Horseback and he directed Sartre’s No Exit. We both got into scandals over how we publicized our respective shows, and were jointly given a joke prize, the “Like Son, Like Father Award” by the student drama society. He was upset to be given second billing.

When people think of me as a harsh theater critic, my personal consolation is that my father was far harsher. He did not suffer fools, or bad theater, gladly. He saw no point in translations which were painstakingly accurate textwise at the expense of good jokes or strong dramatic effects, and was equally contemptuous of directors who piled needless concepts on perfectly workable scripts. I was the rebellious, American-born son in the thrall of post-modernism and the regional theater experimental revolutions of the late 20th century. We would argue endlessly about the merits of Robert Wilson or Peter Sellars.

As distinct as my tastes became, and as independent as I could pretend to be in my writing and researching, my father nonetheless had an enormous impact on how I perceived culture in general. He accepted that there could be high artistry in all fields, and could be as enamored of a great Bugs Bunny cartoon as he was of Moliere or Oscar Wilde. He would tell me about favorite radio shows and music hall acts from his childhood—The serialized Quatermass Experiment or the comedians Nosmo King or Arthur Askey—and make them seem as important as the most renowned classical works. He made me a lifelong fan of The Marx Brothers, Apuleius, The Goon Show, Alfred Jarry, Gilbert & Sullivan, Wagner, Rod Serling, Christopher Marlowe, Leslie Charteris’ Saint mysteries and the medieval mystery plays.

I’ve maintained the open-mindedness he encouraged in me throughout my life, and now try to instill it in my own children. My father and I could spend a night in Boston at a Brecht play or a Monteverdi opera, then hurry home to catch Benny Hill or You Bet Your Life reruns on Channel 56. He didn’t share many of my diverse musical tastes, but understood the need for authenticity in shows he was directing, and would ask me to mix soundtracks of raucous ‘20s jazz for a production of Anouilh’s Ring Round the Moon and delved in Devo when he once considered staging Elmer Rice’s The Adding Machine. He’d hear odd sounds emanating from my room and, months later ask “What was that awful music you were playing? I might be able to use that in…”

My father’s death hit me hard, coming at a time of uncertainty, depression and failure in my own life. It took me about a year of disoriented remorse and grieving before I was fully functional again. November was once the happiest of months for me—my father and I both had birthdays, and we had a long tradition of celebrating by going out to Boston seafood restaurants and then to an opera. His dying in November changed the month for me forevermore.

You might discern from the above that my respect for my father bordered on hero worship. It took decades of aging on my part for me to start appreciating him as a fellow human being. He died at the age of 59, and I am now in my early 50s, so my perspective of him has lately changed a great deal. People who’ve known both of us will comment on the physical resemblance between us, but other than that my father and I developed striking different personalities. He was loud and theatrical and outspoken and supremely self-confident; I am softspoken and was an extremely shy and awkward child. He was a great actor; I’m a lousy one. He had an extraordinary memory; I need to take a lot of notes. He had prejudices and political opinions which I find distasteful in the extreme, and probably vice versa. We both drank and smoked a lot, but I gave it up at a younger age than he did, and blame him for making those vices seem attractive at all. The main things we had in common: we both wrote fast, with little need for a second draft; and we didn’t mind living in squalor. We spent a couple of summers living together while my mother and sisters were elsewhere, and it was like a production of the Odd Couple with two Oscar Madisons. My father once used the oven to dry out some tiny clay seagulls he’d molded for his railroad, and forgot to turn the oven off for three days.

We could enrage each other, and sometimes could simply not comprehend each other, which was most maddening of all. But we always got along, and could always get out of a bad argument by clearing the air with a hideously bad joke. My father had the loudest laugh of any human being ever, and if you caught him offguard with a snappy comeback, it was like setting off fireworks. I once whispered something to him during a silent-film screening in a graduate seminar that had him howling until he wept—and the professor teaching the class couldn’t dare eject the chairman of the department from the room, which to me made it even funnier.

It was fitting this year to mark the anniversary of my father’s death by seeing an adaptation of Euripides by a student director. On my walk home, I could imagine the entire conversation we’d have ab0ut it if he’d gone with me. He’s still very much a presence in my life. When, a couple of months ago, I was interviewed for the Yale Cabaret production This., an oral history project largely about loss and grieving, one of the questions was about items of great significance to me. I reached into my pocket and pulled out a set of battered orange “worry beads” my father bought himself on one of his many trips to Greece. When he died, I inherited the beads—a cheap airport souvenir item which I have now kept close at hand for over two decades. When I take them out of my bedroom drawer every morning, I greet him with a chipper “Hi, Pete!”

We even continue to be occasional collaborators, me in the mortal realm and him in manuscript form. I am in possession of numerous translations he did for stage productions—three Euripideses, three Molieres, a Racine and more—which were never published. I’ve been editing and updating them for hopeful publication, working them over in the same way I used to as a teenager when he needed to infuse a script with contemporary slang, or needed a chapter in one of his theater history books to reflect theories of the generation after him.

I thus celebrate my father’s life daily—with keepsakes and through efforts like this blog, which he truly would have dug. I am finally deeply at peace with his untimely death. He was a man of enormous appetites, all of which impacted on his health, so while it was a shock and injustice to have him die at 59, it’s impossible to think of him making it into his 80s, as he would be now. He also was representative of a British post-war era grounded in The Goon Show, Beyond the Fringe, Richard Burton, Olivier/Gielgud/Richardson, James Bond novels and a diehard classical canon. Not sure how much he’d want to be teaching in this era.

So what I miss is the dog walks and the trips to model train exhibitions and all those November opera-and-dinner dates and constant debates about theater. Rest in peace.