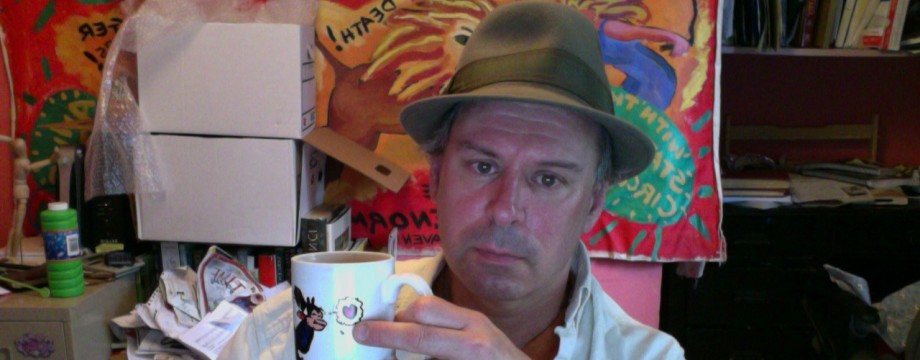

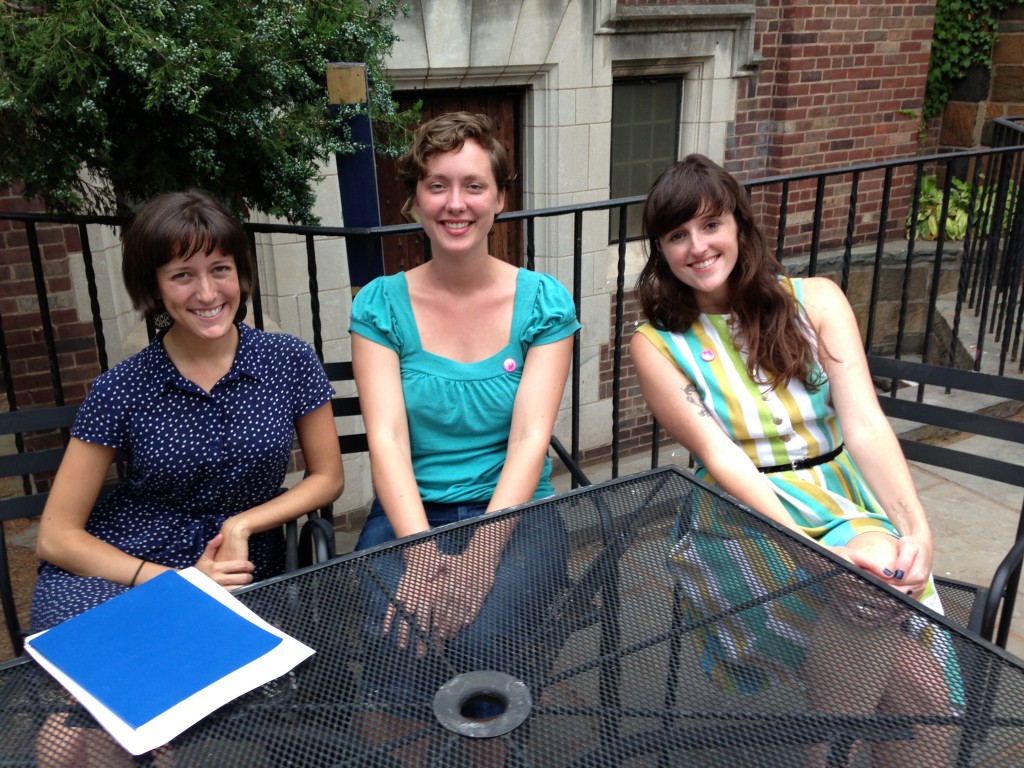

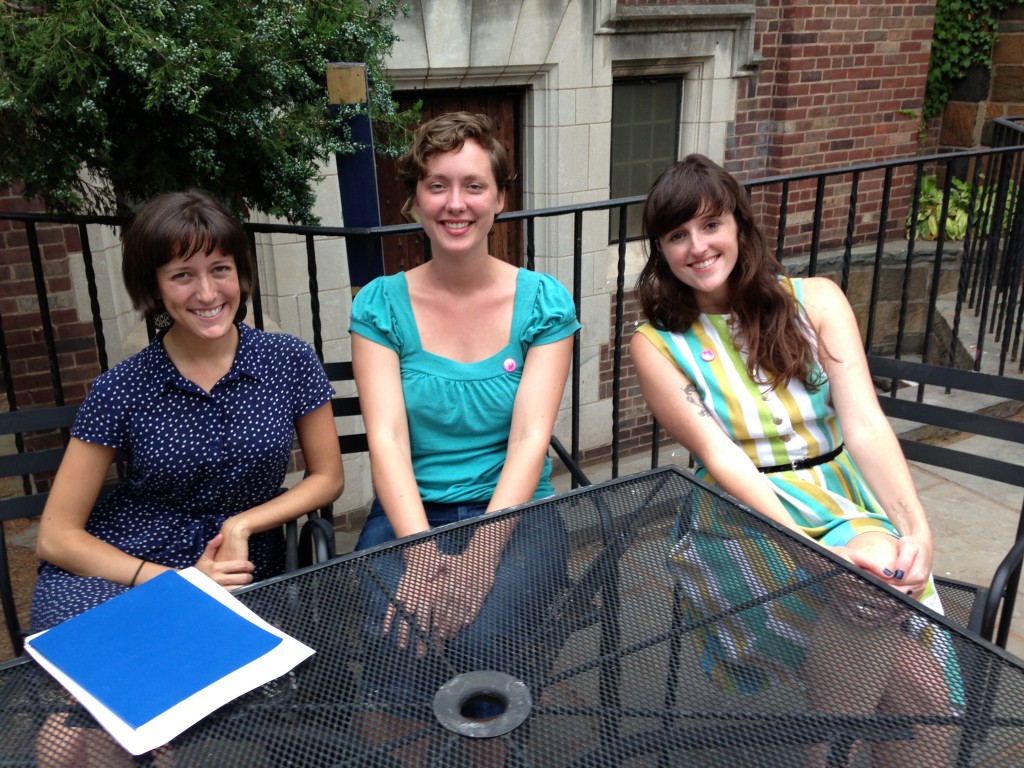

Whitney Dibo, Lauren Dubowksi and Kelly Kerwin, the new co-artistic directors of the Yale Cabaret.

Whitney Dibo and Lauren Dubowski and Kelly Kerwin have been hunkering down over a pile of play proposals since last week, figuring out what will make it into the Yale Cabaret’s 2013-14 season. Nearly 20 proposals were received for the remaining six slots of the fall semester.

Tomorrow we’ll all know what they decided, but there’s a lot more to a Yale Cabaret season than scripts and schedules. This is an institution which, by design, gets a whole new management team every year. Then that group produces some 20 separate plays, for a six-performance weekend each, during the school year. They do this whilst juggling their academic obligations at the Yale School of Drama. This can lead to a kind of inspired extracurricular chaos. Projects change shape quickly. Back-up plans are as important as plans. Artistic relationships blossom. Audiences come in order to be surprised.

This is a rare year in which the entire co-artistic team is female. Just as rare is the fact that Dibo, Dubowski and Kerwin all come from the Yale School of Drama’s Dramaturgy program; Cabaret artistic directors have most frequently come from the Directing program. But since even the most hands-on artistic directors tend to direct only one or two cabaret shows a year themselves, and there are plenty of directors around, it’s possible that the dramaturg incursion makes more sense managerially. “Artistically, one of the most useful things a dramaturg can bring to the table is the outside eye,” Dubowski says.

Perhaps rarest of all, as the three partners told me in an interview yesterday afternoon in the Cabaret garden at 217 Park Street, they will be changing how Cabaret shows are prepared.

This does not mean that the co-artistic directors are imposing some overarching conceptual vision, or altering work for ulterior motives. Far from it. Dibo, Dubowski and Kerwin see themselves as curators. They seek a balanced season, but have wisely not decided beforehand what that balance might entail. They are open to all sorts of fresh ideas. They will contribute heavily to each show’s production process by doing what they have been trained to do as dramaturgs—serve as extra eyes and ears, guiding the work with the useful insight that comes from being slightly removed from what the directors and actors and designers are doing.

To this end, they are creating a new role at the Cabaret: the Creative Producer. Each show will have one, charged with the task of making the show the best it can be. “It’s something we’ve seen at the theaters we’ve worked at,” Dibo says. “The institution has a vested interest in every production. We want them to flourish. It’s a ‘the buck stops here’ mentality.” To which Kerwin adds, “It’s one thing to take a risk. It’s another to not feel the institutional support when you take a risk.”

The new co-artistic directors have seen a lot of new plays developed, here at Yale and also in the thriving small-theater cities from which they hail. Dibo and Kerwin are from Chicago, while Dubowski comes to Yale from Philadelphia. “We come from ego-less cities,” they allege, where they’re used to friendly and open collaborations among artists.

While championing new works, these dramaturgs are also highly respectful of Cabaret traditions. They’ve remodeled the walls of the basement theater’s lobby area to highlight shows from the Cabaret’s illustrious past, going back to the 1970s and spotlighting such esteemed alums as Meryl Street, David Duchovny and Mark Linn-Baker.

“It’s about how we see the Cabaret as an institution, and how we see our team,” Dubowski says. “We knew we could work together, and create something that’s greater than the individuals involved.”

“We’re very much on the same page,” Kerwin adds. “Very different people, but complementary.”

This shared goal of “wanting to elevate artists in our communities,” as Dubowski puts it, involves asking the same questions over and over. “Why here?,” Kerwin says, “and why now?” Projects should be “relevant to now” but also “uniquely suited to the Cabaret space.” As working dramaturgs, the co-artistic directors all know of great scripts that are getting workshopped around the country. But it would be wrong, they feel, to produce something which doesn’t fit the special needs of that long low-ceilinged underground Cabaret room, or its particular audiences. “One of the questions we ask,” Kerwin says, “is ‘Could that get a production elsewhere?’ There are shows which are great shows, but wouldn’t have anything added to them by being done at the Cabaret instead of somewhere else.”

Kerwin, Dubowski and Dibo picked the initial three offerings of the Cabaret’s fall semester well in advance of the others, to demonstrate the sort of balance they’re seeking. First up, Sept. 19-21 is We Know Edie La Minx Had a Gun, a new work directed by Kelly Kerwin and co-written by her, Helen Jaksch and Emily Zemba. It is a mystery of sorts, which “dives into the sensationalism surrounding the life and death of a fabulous drag queen.”’

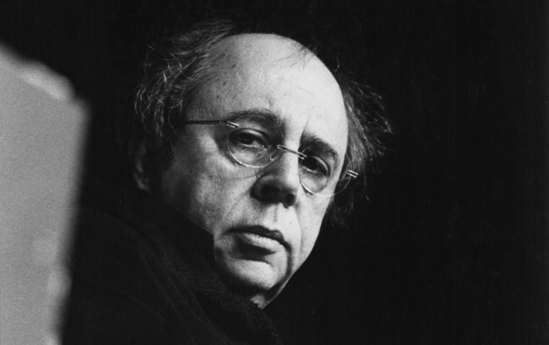

September 26-28 brings a suitably claustrophic production of Amiri Baraka’s subway car-bound classic Dutchman. Amiri Baraka (who wrote the play in the early ‘60s when he was still going by the name Leroi Jones) has spoken at Yale many times, as well as at the International Festival of Arts & Ideas. Dutchman remains as vital as its playwright does, examining modern social relationships and civil rights in a manner that remains provocative and relevant.

The third show of the Cabaret 2013-14 season, and the only other one to be announced thus far (patience—we’ll have the rest tomorrow) is The Most Beautiful Thing in the World, conceived and directed by Gabe Levey. The last show at the Cabaret conceived by Gabe Levey also starred Gabe Levey (now in his final year of the Yale School of Drama acting program), but this one doesn’t. It stars Kate Tarker, and involves motivational speaking, audience participation, clowning and other empowering stuff.

So… balance. Old, new, dark, light, new faces, veterans.

“We view this very much as a curatorial position,” says Dubowksi of the trio’s artistic director obligations. Besides measuring out the tones and tempos, they’re looking to involve a wider range of students, especially from the 2015 and 2016 graduating classes, in the Cabaret when possible.

Along with new Yale Cabaret managing director Shane Hudson, the co-artistic directors’ communal goal is to “acknowledge the past, and break new ground.” Sounds like the Yale Cabaret we know and love, with a wonderful sense of self-awareness about why this little theater is so immensely important.

The interview in the Cabaret garden. Photographed by Sally Arnott, age 9.