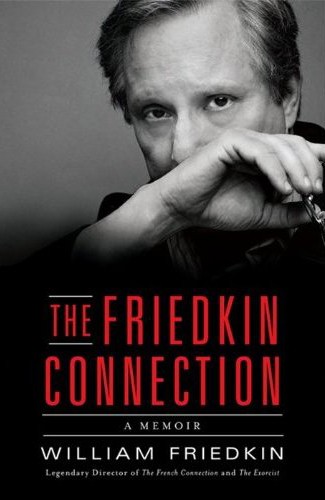

The Friedkin Connection—A Memoir

By William Friedkin. (HarperCollins, 2013)

The title of William Friedkin’s memoir alludes to the fact that he directed the action film classic The French Connection, with its revolutionary car-chase sequence. A tagline on the book’s cover mentions that more explicitly, and adds that he’s also the “legendary director” of The Exorcist.

But this is a book for theater enthusiasts as well. Perhaps primarily for them, since the collaborative relationship which Friedkin prizes most, the one which is woven most strongly through the narrative, was with Harold Pinter.

Friedkin has done many noteworthy movie-movies. Many are crime thrillers, from the comical The Brink’s Job and Deal of the Century to the controversial gay-nightclub serial-killer mystery Cruising to the underrated Sorcerer. But there’s a consistent line of theatrical adaptations on his resume, starting with his surehanded adaptation of Pinter’s The Birthday Party in 1968. That the risk-averse Pinter took a chance on a largely untested young director for the film version of one of his breakthrough works is a compliment which Friedkin does not take lightly. He describes making The Birthday Party (which starred the great stage actor Robert Shaw, often typecast as heavies in films like those which Friedkin would later make) with much greater detail than he allows for either The Exorcist or The French Connection. He always continually returns to Pinter, as a friend and as an influence, throughout the book. It’s more compelling in some ways than Julian Sands’ full-length one-man show about his own connections to Pinter.

The Pinter content is bracing enough: “From a creative standpoint,” Friedkin writes, “the year I spent with Pinter on the screen adaptation of his first play was an awakening and a life-changing lesson in the art of creating serious, suspenseful drama.

Another stage-derived Friedkin film, The Night They Raided Minsky’s, was released the same year as The Birthday Party. A famous flop which nonetheless has many bright moments and a stage-happy cast headed by Jason Robards, Bert Lahr and British music hall veteran Norman Wisdom. Minsky’s mythologizes the waning days of the American vaudeville tradition. Friedkin’s forthcoming about that project’s failures: “There were many problems with it, but the biggest was my own ineptitude. I had researched the period but I didn’t know how to convey the right tone.” He even at one point asked the film’s co-producer Norman Lear to fire him.

Friedkin’s next film after The Night They Raided Minsky’s, and his last before he hit the bigtime, and won an Oscar, for The French Connection was The Boys in the Band. Friedkin gives some useful background to how he came to be involved with this respectful stage-to-screen translation of Mart Crowley’s seminal gay social drama The Boys in the Band. At the same time, the director is clear about how he came late to the party, following the play’s extraordinary success Off Broadway. Crowley, Friedkin says, “was overwhelmed by the play’s success, having known mostly failure in his creative endeavors up to then. Mart insisted we use the play’s original cast, to which I agreed. They had come to embody their roles and worked well as an ensemble. We also agreed we’d have to achieve a realistic tone, and it would of course be an entirely new staging. He had ideas for opening up the film with a visual prologue in a handful of New York locations, but it needed the claustrophobia of a one-room set to retain its impact. The trick was to keep the film claustrophobic but cinematic.

Just as he notes that an exchange in The French Connection is reminiscent of the interrogation scene in The Birthday Party, Friedkin links shooting The Boys in the Band back to what he learned lensing Pinter’s play. “The Birthday Party had sharpened my sense of how to capture a scene without allowing the camera to be intrusive.” Friedkin insisted that the actors rehearse for a couple of weeks prior to filming, which they at first resisted because they had already been performing the play for so long. The result? “Today, it’s generally regarded as a landmark film. I say this in all modesty because I believe its power lies in Mart’s script and the brilliant performances by the entire cast, which went virtually unrecognized at the time.” (A fuller appreciation of The Boys in the Band can be found in Crayton Robey’s smart 2011 documentary Making the Boys.

Friedkin is still out there making movies, and still working with accomplished stage dramatists. His two most recent films, Bug and Killer Joe, both came from plays written by Tracy Letts. A whole chapter of his memoir is devoted to the Letts films, very much in the present tense of Friedkin’s illustrious career.

Oh, and somewhere along the line Friedkin, who came to filmmaking not from a theater background but from non-fiction documentaries, started directing operas. The Friedkin Connection stands out among film-director memoirs due to its self-deprecating tilt, its prizing of strong collaborative relationships and loyal friendships rather than personal accomplishments, and its willingness to travel outside its filmmaking field to pay tribute to other media. Mainly theater. Nice connections.