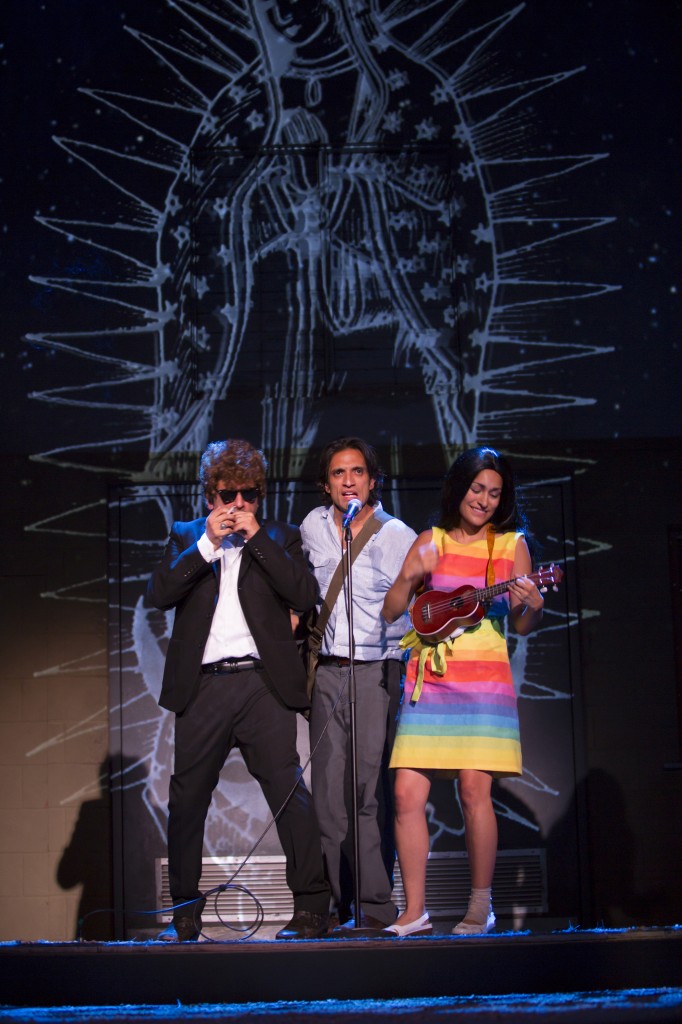

Richard Ruiz (center) croons Neil Diamond’s “America” at the manic conclusion of American Night—The Ballad of Juan Jose, through Oct. 13 at the Yale Repertory Theatre. Photo by T. Charles Erickson.

American Night—The Ballad of Juan Jose

Through October 13. Presented by the Yale Repertory Theatre at the Yale University Theater, 222 York St., New Haven. (203) 432-1234, www.yalerep.org

By Richard Montoya. Developed by Culture Clash and Jo Bonney. Directed by Shana Cooper. Choreographer: Ken Roht. Scenic Designer: Kristen Robinson. Costume Designer: Martin T. Schnellinger. Lighting Designer: Masha Tsimring. Sound Designer: Palmer Hefferan. Projection Designer: Paul Lieber. Production Dramaturg: Lauren Dubowski. Vocal and Dialect Coach: Beth McGuire. Singing Coach: Vicki Shaghoian. Fight Director: Rick Sordelet. Casting Director: Tara Rubin Casting. Stage Manager: James Mountcastle.

American Night is a societal nightmare play in the chaotic tradition of The Adding Machine and Beggar on Horseback. Such self-pitying silliness really sells in times of economic uncertainty. Or maybe people just like it because it’s fast, furious and very funny.

Juan Jose is a Mexican everyman who has come to America but feels incomplete with just a green card. “Alien” still means alien, he laments. So he’s in the workroom at his job studying for his U.S. Citizenship exam. He crams until he’s weak, rests his head for a moment on a table, then BAM! POW! He’s asleep! It’s the least restful dream in theater history, a fever-dream on par with Dorothy’s twister-swept visions in The Wizard of Oz.

It’s funny to say this, but playwright Richard Montoya should be commended for NOT making his characters deep and human. Everybody’s a caricature, everybody’s mocked with gross stereotypes, everybody but the guy playing Juan Jose, Rene Millan, plays multiple roles. Everybody speaks in absurd Southern, Hispanic, Asian or WASP accents. When in doubt, the actors dance, masterfully choreographed for the ensemble’s varied abilities by Ken Roht. (If you’re a producer planning a revival of The Full Monty or Stepping Out, hey, hire Ken Roht.)

For her part, director Shana Cooper must do a very different thing than she did when she was last at Yale Rep. A couple of seasons ago, Cooper found a new youthful style to fit student actors who both jump from balconies and scan Shakespeare metrically like pros. This time, she is in obeisance to an existing style of controlled chaos favored by playwright Richard Montoya and developed by the legendary theater troupe he co-founded, Culture Clash. Jo Bonney, who directed earlier productions of this play at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival and in California at the La Jolla Playhouse and Culver City’s Kirk Douglas Theater, shares a “developed by” credit with Culture Clash, and a second Culture Clash founding member, Hector Siguenza appeared in roles now done at Yale by Richard Ruiz. Cooper and a game cast–the perfectly cast Ruiz, the multitalented Nicole Shalhoub and two especially sturdy supporting cast members with serious Yale Rep cred—Felicity Jones, who appeared at the Rep in Master Builder, A Woman of No Importance, Lulu and Ladies of the Camelias, and recent Yale School of Drama grad (and Yale Summer Cabaret stand-out) Austin Durant. To find a cast that is so uniformly brassy and fearless is a trick, even if some of the trashier routines are beneath their talents.

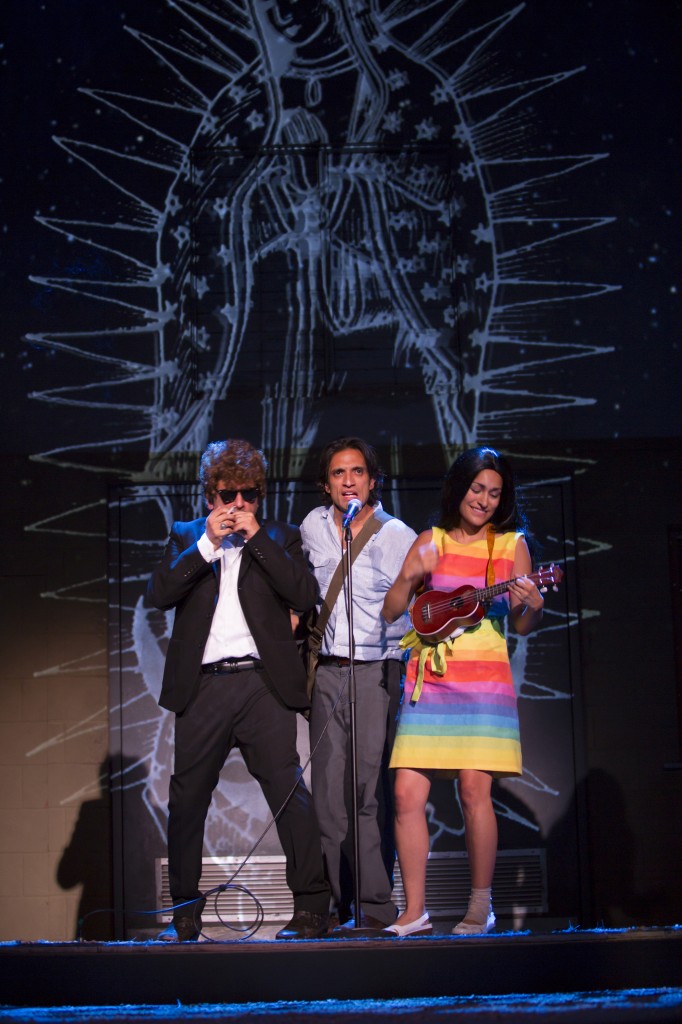

Playwright/performer Richard Montoya as Bob Dylan, Rene Millan as the title character and Nicole Shalhoub in American Night—The Ballad of Juan Jose at the Yale Rep. Photo by T. Charles Erickson.

The style is a colorful, cartoony one, not a raw frolic such as The Fatal Eggs, which the Yale Cabaret admirably began their fall season with last weekend. It’s a more composed, calculated, brightly illuminated form of comedy. The actors fan out carefully about the stage, and seldom clump. They declaim their jokes like opera singers. Behind them is an everchanging backdrop of projected photographs, from nature scenes to montages of social unrest in the 1960s. Befitting the word “ballad” in its title, the show stops cold a couple a times for some beautiful musical interludes.

American Night has a larger cast than most Culture Clash shows. When the essential troupe, a trio, appeared at Yale a decade or so ago in their signature work, Culture Clash in AmeriCCa, they augmented that plotless, sketch-based evening with fresh material commenting on culture divides here in New Haven. The added material really took over, since the cast directly impersonated and parodied local celebrities and politicians.

The decidedly more plotbound American Night doesn’t have the same splash of local content, but as the general election approaches there are plenty of Romney (Mormon), Obama(-care), 47%, 99% and similar references to make the show seem more current than it really. A lot of the lampooning, sadly, concerns classic historical themes which haven’t changed much over the centuries: white settlers oppressing native cultures and minorities, immigration struggles, the injustice of internment camps.

The humor, and the drama, is excessive and heavy-handed. But you can’t say it’s not consistent. Right out of the gate, in the pre-show “turn off your cell phones” announcement, we’re told that violators “will be deported to East Haven.” Later, we get KKK-sheeted bigots, Jesus Christ himself being hassled by border police, and the entire cast in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) vests dancing to the old rap novelty “Ice Ice Baby.” Luckily, we also get more subtle laughs such as the observation “Why do Mexican-Americans love Morrisey?” or that a disgruntled hippie is “going back to Greenwich,” or a union leader’s crack about “student labor” when the backstage crew (indeed composed partly of Drama School students) engineer a trapdoor effect, and even a bizarre reference to the Christina Ricci opus Black Snake Moan.

Is there a point to get across here? Yes, and at one point it’s articulated thus: “America Sucks—but it swallows.” American Night is about the anxiety of craving freedom in a place universally known for spreading yet, but which is just as likely to deprive you of it. It’s a nightmare that many can’t avoid, and one well worth considering. The fact that we can laugh at such spectacular insensitivity means there may be hope for us all. Let’s hope this dream is a wake-up call.

Rene Millan as Juan Jose and Nicole Shalhoub as a braces-sporting teenaged Sacagawea in American Night—The Ballad of Juan Jose at Yale Repertory Theatre. T. Charles Erickson photo.