The performance installations and playscapes at the Kid City children’s museum in Middletown have always been impressive. The newest is a “Celebrated Bathing Fluid Dispensary” credited to the inventor Pulaski Nostrum (1854-1906). Through lit signs, machine helps participants soap, rub, rinse and dry their hands—all to the rhythm of a mechanical bicyclist.

Kid City claims this is a genuine relic from an earlier era of handwashing, bequeathed to the play place by Nostrum’s great-niece Berniece. According to her wishes, a posted document by the museum’s director states, the Bathing Fluid Dispensary is “installed in a replica of the red-and-green paneled cloakroom of her Great Uncle’s beloved club, the Archeological Society of Washingtown.”

Such sudsy subtlety is not lost on children. A magical bit of scenic design.

Kid City Set Piece

Who’s in the Header Photo?

It’s me and Marvin Hamlisch!

He was at the Shubert theater back in the ’90s for one of his patter-filled “Evening With…” piano concerts in which he discusses his long and varied career. At the after-party in the Shubert mezzanine, I was briefly invited to shake Hamlisch’s hand, during which I uttered incredulously, “I’m just awestruck to meet someone who accompanied Groucho Marx.”

Hamlisch was the pianist for Groucho’s concerts in Ames, Iowa and at New York’s Carnegie Hall. The shows were recorded and released as the An Evening With Groucho album.

Marvin Hamlisch grinned ear to ear at my admission, and proceeded to regale me with anecdote after anecdote about his time with Groucho. He had to be dragged away by Shubert administrators to do the obligatory handshakes with the bank presidents and others who’d co-sponsored his concert. As soon as he’d acknowledged the bigwigs, he’d spin back ’round to me and continue, “…and then Groucho said to me..”

I’ve since seen Hamlisch play outdoors with the New Haven Symphony orchestra. I’ve seen him conduct Pops concerts. I saw one of the final performances of the musical version of Sweet Smell of Success on which he collaborated with John Guare. I saw a wild low-rent tour of Hamlisch’s underrated musicalization of Goodbye Girl, which starred Eddie Mekka (Carmine from Laverne & Shirley).

I just found a paperback copy of Rex Reed’s 1977 essay collection Valentines & Vitriol for free at New Haven Reads, and was enjoying the Hamlisch profile, in which the composer is justifiably defensive about how some of his most famous stage and movie scores were perceived. He says that with A Chorus Line he deliberately downplayed some tunes he could have easily turned into showstopping hits so that the ensemble-build show could build dramatically in a more democratic manner. He’s also aggrieved by suggestions that he simply ripped off Scott Joplin for his Oscar-winning The Sting score, noting that he’d always given Joplin full credit for the tunes, that Hamlisch didn’t take “arranger” royalties which he easily could’ve, and that it’s the arranger, not necessarily the original composer, of movie soundtracks that gets nominated for Oscars.

Marvin Hamlisch deserves a lot more attention and respect for what he’s contributed to theater and film history. Starting with that he’s real nice to Groucho fans.

The Acorn Doesn’t Fall Far from the TV

Acorn Media has started its own sort of selective Netflix, a Britflix if you will. It’s actually called AcornTV.

Acorn is well known to theater geeks as the distributor of such stage-centric DVDs as Discovering Hamlet (reviewed here), the three-DVD television rendition of Alan Ayckbourn’s The Norman Conquests (which I’ve been meaning to review here for a while now, and will soon), John Gielgud’s Ages of Man series, Broadway’s Lost Treasures, Sondheim! The Birthday Concert, the box set of ten star-studded Gilbert & Sullivan TV presentations from the 1970s, the nonmusical Ray Winstone rendition of Sweeney Todd, a host of British drama series which happen to feature stage icons… If somehow you’re theater-savvy enough to read this blog and have somehow escaped the allure of Acorn, the “Performance” subset of their online catalogue is here.

The online streaming service, which will spotlight just a fraction of Acorn’s ample offerings, began last week. You can sign up now for a few weeks of free sample streaming. Starting in September it’ll be a paid subscription service costing $24.99 a year.

The service is concise: a programmed schedule of six series of “British mysteries and dramas” available online for six weeks each. The shows are staggered so that something new comes onto the sched every week. According to a press release, “There are six seasons and more than 40 hours of programming offered at any given time.”

This system of course favors TV series over other Acorn-affiliated shows. Perhaps some of those theatery specials and documentaries may get on yet.

But who’s complaining? I’ve already watched the first three 90-minute episodes of Foyle’s War, the lush and leisurely WW2 Sussex-set mystery series starring Michael Kitchen, famed RADA-schooled veteran of landmark productions of plays by Pinter and Stoppard.

I’ve found Acorn’s menu of shows manageable and inviting.

On the current streaming slate: the 12-part Brideshead Revisited (tup through July 31), six episodes of The Forsyte Saga (up through Aug. 7), three two-part installments in The Far Pavilions (through Aug. 14), nine adventures of Agatha Christie’s Poirot (through Aug. 21), the first season of Upstairs, Downstairs (through Aug. 28). Foyle’s War, with four long episodes available, is up through Sept. 4. Forthcoming in August: Wish Me Luck and Derek Jacobi’s Cadfael mysteries.

Richard The Slurred

My friend Stephen Kobasa, with whom I’ve attended many impersonations of Shakespeare plays, alerted me to this. It appears to have been posted by its performer, Jim Meskimen, just a couple of days ago, to promote a Hollywood performance at the end of this month.

I laughed loudest at the Paul Giamatti one, because I’ve actually seen Paul Giamatti do some Shakespeare, 20 years ago when he was at Yale.

Pie Squared

BBC Radio 4’s daily arts news show Front Row sliced a terrific bonus performance-art story out of the Rupert Murdoch testimonial pie-throwing fiasco. (See previous post.) The show contacted the fabric artist whose large linen piece “Debate” hangs in the hall where Murdoch was being grilled about his part in the News of the World phone-hacking scandal. When the pie-tossing incident occurred, the hearing was stopped and the TV camera was turned to the wall, on which Kate Blee‘s artwork appeared.

You can hear the BBC’s interview with Blee here; it’s not indexed on the BBC website as part of the program, since it was probably a very late add-on. It starts at six minutes and 17 seconds into the show and lasts just over three minutes. The Art Newspaper did its own piece on Blee’s Debate, here.

Besides analyzing the scenic design for this impromptu performance, the Front Row bit is also notable for host John Wilson’s referring to the assailant, Jonnie Marbles, as a “so-called comedian.” A lot of commenters on the various YouTube videos available of Marbles monologues don’t seem to appreciate his humor. But whether or not you like his politics, he’s doing lengthy, scripted humorous monologues, and I’d say that defines him as a comedian.

Huffington Post profiles Marbles, and embeds, some of his routines, here.

Yum! Pie!

British comic Jonnie Marbles tried to hit Rupert Murdoch with a pie—‘or rather, “a pie plate of foam,” as an Associated Press story unfancifully labeled it—during the media magnate’ s testimony in the News of the World phone hacking scandal.

Marbles was deflected by Murdoch’ s wife Wendi Deng before the pie—for theatrical purposes, this was clearly a pie—could hit its target.

The news item sent me scurrying to the bookshelves, in two directions: to my film books, for studies of pie throwing in silent movies, and to my collection of radical lit which bring the satiric craft of pastry flinging into the modern era.

The funniest thing in the world is for one person to hit another with a pie. Crude as this may sound it has made more people laugh than any other situation in motion pictures. It was first discovered twelve years ago and has been a constant expedient ever since without, so far as be discovered, any diminution of appreciation. It has made millions laugh and tonight will make a hundred thousand more voice their appreciation in laryngeal outbursts. It is the one situation that can always be depended on. Other comic situations may fail, may lapse by the way, but the picture of a person placing a pie fairly and squarely on the unsuspecting face of another never fails to arouse an audience’s risibilities. But the situation has be led up to craftily. You can not open a scene with one person seizing a pie and hurling it into the face of an unsuspecting party and expect the audience to rise to the occasion; the scene has to be prepared for. There must be a plausible explanation of why one person should find it paramount to hurl a pie into another’s face. He must have been set on by the other—preferably by somebody larger than himself—and then suddenly the worm turns and sends the pie with unerring accuracy into the face of the astonished aggressor. To this an audience never fails to respond.

—From “The Five Funniest Things in the World,” Photoplay Magazine, September 1918. Anthologized in Photoplay Treasury (Bonanza Books, NY, 1972)

The “pie-in-the-face” prank has a lengthy history with manifestations in popular and folk culture. Like most pranks, pies are acts of ritualized inversion and humiliation. They draw on the power of laughter to unsettle and disrupt. Political pie-throwers carefully craft the symbolism in their pranks, something evident in both the enactment and in the subsequent discussion and documentation of the pie.

Any successful prank is a nuanced and well-crafted event, executed with strategic planning and with anticipated results. When combined with elements of parody and political wit, a prank can offer an entertaining act of social criticism. Pranks operate on and through power dynamics, inverting structures of status and convention. According to journalists V. Vale and Andrea Juno, a prank connotes “fun, laughter, jest, satire, lampooning, making a fool of someone”—all light-hearted activities. Thus do pranks camouflage the sting of deeper. More critical denotations, such as their direct challenge to all verbal and behavioral routines. They undermine the sovereign authority of words, language, visual images and social conventions in general. Regardless of the specific manifestation, a prank is always an evasion of reality. Pranks are the deadly enemy of reality. And “reality”—its description and limitation—has always been the supreme control trick used by a society to subdue the lust for freedom latent in its citizens.

—From “The Theory of Pie” by Audrey Vanderford, contained in Pie Any Means Necessary: The Biotic Brigade Cookbook (AK Press, 2004)

It’s well known that Stanley Kubrick intended to end Doctor Strangleove with a pie fight. The scene was even filmed.

Wendi Deng’s intervention adds a new staging innovation to the pie-throwing dynamic, that of the protective, involved third party. The humor is usually found in a disinterested interloper inadvertently getting in the way of a pie-throw, or trying to avoid getting involved but receiving overflow cream nonetheless.

But the most extraordinary aspect of Rupert Murdoch’s (nearly) getting hit with a pie was that it’s apparently never happened to him before. The BBB’s Pie Any Means Necessary book contains as authoritative a list of well-heeled real-life recipients of pies-in-face as has been compiled, and Murdoch’s not on it.

Jonnie Marbles has explained himself in an article for the Guardian: “I knew it was a tall order: a surreal act aimed at exposing a surreal process was never going to be an easy sell.”

Well, what’s he selling? Revolution, or pie?

Literary Prestidigitation

The branch library a few blocks from here hosted a healthy dinner (with obligatory lecture on how healthy it was) plus a performance by Magic Dan, with guest appearances by a talking puppet bird and a scared live rabbit. Libraries are a heck of a place to see a magic show because when the kiss hip and holler the adults feel compelled to remind them that they’re in a library.

Oh, and the incantatory phrase of the night was not “abracadbra” but this:

“Reading is Fun!”

Bond… St. James Theatre Bond

“After my great undercover work”—Nkosi’s arm swept around the room—“I now know I am quite the actor. I will come to London and work in the West End. That’s where the famous theaters are—correct?”

“Well, yes.” Though Bond had not been to one voluntarily in years.

The young man said, “I’m sure I will be quite successful. I’m partial to Shakespeare. David Mamet is quite good too. Without a doubt.”

Bond supposed that, working for a boss like Bheka Jordaan, Nkosi did not get much of a chance to exercise his sense of humor.

—from Jeffery Deaver’s current bestselling James Bond 007 novel Carte Blanche. Deaver, by the way, is not as stage-phobic as O07: “All the World’s a Stage,” a short story in his collection Twisted, credibly chronicles the problems of actors and playwrights (including William Shakespeare) in Elizabethan England.

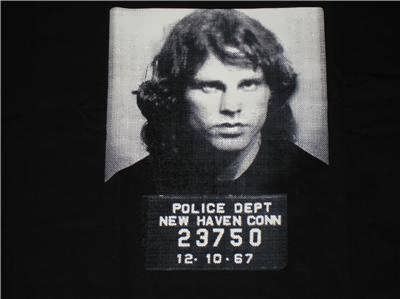

Doors of Perception

All the hoopla earlier this month about the the 40th anniversary of Jim Morrison’s death overlooked the rock icon’s considerable theatrical interests and influences.

Musical theater geeks know that The Doors had the biggest mainstream pop impact with a Brecht/Weill song (“Whiskey Bar”) since Louis Armstrong and Bobby Darin swung Mack the Knife.

Morrison was also an avid follower of some of the leading U.S. experimental theater troupes of the 1960s: The San Francisco Mime Troupe, the Living Theater and the Actor’s Workshop Theatre.

He reportedly attended every performance of the Living Theater’s Frankenstein and Antigone at Bovard Auditorium in San Francisco in February of 1969. He also apparently saw the Living’s Paradise Now half a dozen times, taking full advantage of the audience participation opportunities. There’s a story of Morrison giving Living Theater founder Julian Beck a couple of thousand bucks to get back to NYC from the tour.

Morrison studied the works and theories of Antonin Artaud with poet/activist Jack Hirschman and while best known as a UCLA film student, also studied at the Theater Arts department of the College of Fine Arts, graduating in 1965.

He was great friends with playwright/poet Michael McClure, and they were apparently planning a film of McClure’s The Beard, with Morrison as Billy the Kid. (Hopefully they were intending to make it before he gained all that weight.)

The performance-art and theatrical aspects of Doors shows culminated in obscenity busts. Right here in New Haven, Connecticut, Morrison’s encounter with police officers when he was found cavorting with a fan backstage led to the long improvised onstage monologue from which the cherished quote “Blood on the streets in the town of New Haven” emanated. Morrison was publicly arrested during the concert rant, on Dec. 9, 1967.

The Living Theater had its own police-reviewed theater event when a 1968 Yale Rep performance of Paradise Now spilled out in the streets, causing arrests and recriminations…but no hit singles.