Eugene Barry-Hill (in the Andre role) and Debra Walton (as Charlayne) in a recent production of Ain't Misbehavin' at the Cincinnatti Playhouse in the Park. They both appear in the new production of the show now at the Long Wharf Theater. Photo by Sandy Underwood.

“This Joint is Jumpin’”

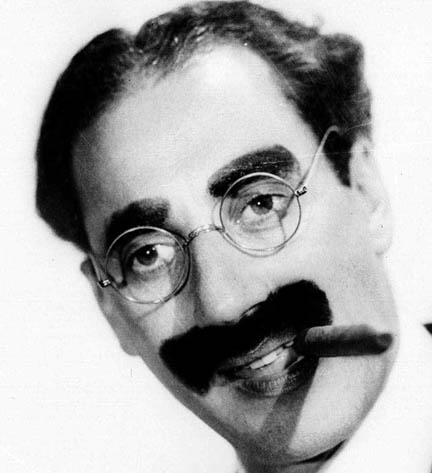

Arthur Faria has lost count of how many times he’s directed Ain’t Misbehavin’, the landmark 1970s Broadway hit which celebrates the life and work of Harlem Renaissance icon Thomas “Fats” Waller and which inspired dozens of similar (mostly inferior) historical song revues and jukebox shows on the Great White Way.

Faria reckons the tally of his previous misbehaviors is in the dozens. But one never knows, do one?

While the total may elude him, Faria remembers the finest nuances of each specific production—from the musical’s first appearance as a one-act revue of Fats Waller songs at Manhattan Theatre Club to its latest revival which has its first preview performance tonight (Wednesday, Oct. 26) on the Long Wharf Theatre mainstage. (Critics get to go Nov. 2; expect a review here next Thursday or Friday. Tix and details at the Long Wharf site here.)

Richard Maltby Jr. co-conceived and directed the original cabaret and Broadway productions of Ain’t Misbehavin’. Faria did the musical staging and choreography. Both men signed on for the Long Wharf revival. Murray Horwitz, who co-wrote the show’s book with Maltby and has been involved in a few other revivals, isn’t along for the ride this time. “Murray takes a back seat to it these dayus,” Faria explained in a phone interview last week. “This production, he did not attend rehearsals. But he’s always invited.”

“Spreading Rhythm Around”

Ain’t Misbehavin’ is not one of those cases where a show’s creators are so protective of their work that the piece is never allowed to be altered. Nor is it one of those situations where an underling with no original ideas of their own recreates the staging or choreography by rote.

Ain’t Misbehavin’ ran for over 1600 performances on Broadway, with performers that ranged from blues shouters to more refined torch song seductresses. Whern Irene Cara from the original Manhattan Theatre Club revue couldn’t be part of the transfer to Broadway, she was replaced by Charlene Woodard, a much different sort of performer.

Ain’t Misbehavin’ was retooled for a national tour starring the Pointer Sisters in 1995 and again in 2008 for American Idol veterans Ruben Stoddard, Frenchie Davis and Trenyce Cobbins.

Doesn’t sound like the producers are all that single-minded in their aesthetic, eh?

The Long Wharf cast includes Eugene Barry-Hill, Doug Eskew, Kecia Lewis-Evans, Cynthia Thomas and Deb Walton.

“T’Ain’t Nobody’s Bizness”

Above all, consider that this is a show that decided from the get-go that they weren’t even going to insist that there be an exact impersonation of its prevailing force, jazz musician and composer Fats Waller. Everything’s open to reinterpretation. “My job,” Faria says, “is to give the show a vernacular, a style of movement.”

The closest character to Fats Waller in Ain’t Misbehavin’—smiling, sly, overweight, wears a bowler hat, plays the piano—is named Ken, after Ken Page, the actor who originated the role. All the characters, for that matter, are named for their original players: Nell (Carter), Andre (DeShields), Armelia (McQueen) and Charlayne (Woodard).

“At first, I wasn’t sure where we would find Fats Waller. Then, in the rehearsals, it occurred to all of us that all of these people are elements of Fats Waller. You get the feeling that these are Fats’ five closest friends. Ken Page was 22 when he started. It would have been easy to say, OK, you’re Fats Waller. That would be too easy. We didn’t want to do that. We started by staging the numbers in a period style. No dialogue. No book to rely on. You’re loaded with impression.

“That Ain’t Right”

So even while allowing for new ideas, respect for the formative voices is upheld, because they were so integral to what the show became. “We bring a lot of tradition when we come into rehearsals,” Faria says.

He talks about rehearsals a lot. He’s proud of the fact that Ain’t Misbehavin’ looks improvised and loose. Yet each gesture has been extensively worked out, and the show is as “set” as if it had much more rigorous technical needs.

While he welcomes innovation, Arthur Faria is insistent that the secret to Ain’t Misbehavin’ is intense rehearsal. He’s intentionally lost the chance to work major stars into various productions of the show because he knew they wouldn’t be up to the workload. He calls Nell Carter, who made her name in the original cast of the show and made it seem so effortless, “one of the hardest working women I’d ever met in my whole life.”

He despairs of some of the productions that he hasn’t directed and has been invited to. “Most people don’t get it. They think it’s a cheap show—throw a few boas on the women and just do it. They don’t get it. They don’t see the beauty.”

“Squeeze Me”

Speaking of beauty, Faria credits Ain’t Misbehavin’ with introducing mainstream white Broadway audiences to the concept of a large black woman being beautiful.” While acknowledging that “There are heavy-set women in the show because those are who auditioned for us,” the physical and vocal diversity of the performers was crucial to Ain’t Misbehavin’’s widespread appeal.

“I was very young when I first did the show. I wanted to load it up,” Faria says. He still does. During the Long Wharf rehearsals he decided to add a mirror ball—“not a disco ball; an old-fashioned ballroom mirror ball.” It’s for the scene where “How Ya Baby” glides into “Jitterbug Waltz.” The numbers demonstrate how subtle and dramatic Ain’t Misbehavin’ can be, amid all its blowsy grandiosity. Faria fashioned this dance into sharply different pairings—one couple tentative and shy, another antic and ass-grabbing.

“Lookin’ Good But Feelin’ Bad”

In other areas, Faria says “I wanted this show to have a bottom, not just the lightness. Fats Waller had a wonderful life, but he also had a darker side.” Some of that comes out in song choices such as the potsmoker’s lament “The Viper’s Drag.” Faria admits his staging of that number was inspired by the over-the-top anti-pot B-movie Reefer Madness. The hysteria fit with his candid belief that “we knew our audience would be primarily white. I wanted this to be a white person’s take on what a black experience might be, from the insult songs like “Your Feet’s Too Big” to the beautiful songs and the dark side.” The show seeks to turn caricatures and cultural stereotypes on their head, just as Waller did, slyly ingratiating itself while making audiences challenge some of their cultural biases.

“I Can’t Give You Anything But Love”

Faria’s reverence for Waller has not subsided over the years. He describes his glee at being gifted with a hat which belonged to Waller. When working with the singer Patti Austin, he got to know her mother Edna, who gave Faria the greatest compliment he’s ever gotten: “Fats would have loved this. He’d love all the details.” Faria was astonished to learn that Edna Austin had been one of the Waller Girls on the records and film shorts Waller made in the 1930s.

The intention of the Long Wharf production was to restore some of the intimacy which Ain’t Misbehavin’ had in its earliest incarnation at Manhattan Theatre Club. It would be a stretch to say that’s really doable. The show was much shorter then, and had a different shape. “The show was only 30 minutes long. We might have said, ‘OK, that’s Act One, and just created a second act, but instead we took the entire show apart and reconfigured it.”

Another intimacy obstacle: the actors at Long Wharf will outfitted with Lavalier microphones. “You can’t see them—it ruins the illusion of the production for me,” Faria says, but microphones nonetheless.

Eugene Barry-Hill (Andre) and Doug Eskew (Ken) in the Cincinnatti Playhouse in the Park production of Ain't Misbehavin'. Both men are now in the Long Wharf production. Photo by Sandy Underwood.

“Find Out What They Like”

On the other hand, Faria declares the Long Wharf version “doesn’t resemble a version done anywhere else. We’ve done it at Cincinnatti Playhouse in the Park which has a long thrust stage”—a Long Wharf mainstage distinction—“but that theater is huge. I’m taking advantage of the thrust here. It brings the show closer to the audience. So Long Wharf will definitely have the same sense of intimacy that the original show did. You can not escape this cast!”

Nor should you want to. “The cast have all done the show before, and maybe four of them have worked together at different times, but they have never all performed together. You put these five together, and the mix is something we’ve never had before.

“The cast has to be willing to reinvest itself totally. We reinvent this show regularly.”