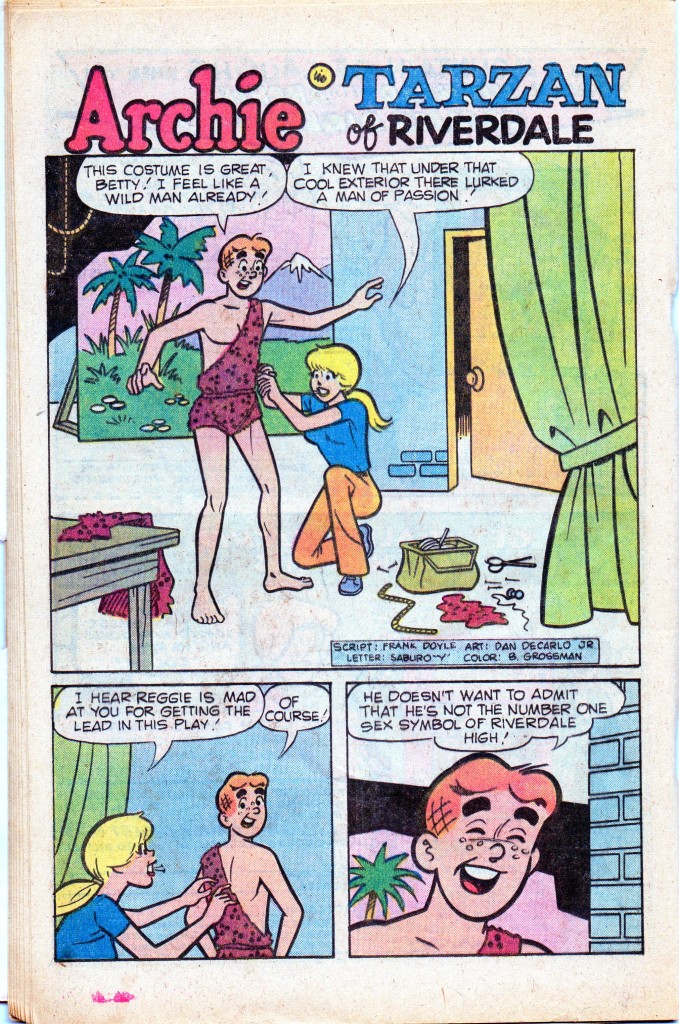

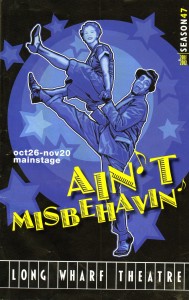

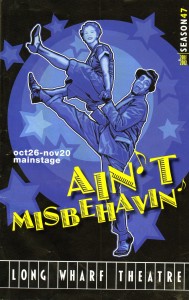

Debra Walton, Cynthia Thomas, Doug Eskew, Kecia Lewis-Evans and pianist/musical director Phillip Hall in the Long Wharf Theatre presentation of Ain't Misbehavin'. The show, directed and choreographed by the show's original team of Richard Maltby Jr. and Arthur Faria, misbehaves through Nov. 20. Photo by T. Charles Erickson.

Ain’t Misbehavin’—The Fats Waller Musical Show

Through Nov. 20 at the Long Wharf Theatre, 222 Sargent Dr., New Haven. Conceived by Richard Maltby Jr. & Murray Horwitz. Created and originally directed by Richard Maltby Jr. Original choreography and musical staging by Arthur Faria. Musical adaptation, orchestration and arrangement by Luther Henderson. Vocal and musical concepts by Jeffrey Gutcheon. Musical arrangements by Jeffrey Gutcheon and William Elliott.

Directed by Richard Maltby Jr. Choreographed by Arthur Faria. Musical director: Phillip Hall. Set design: John Lee Beatty. Costume design: Gail Baldoni. Lighting design: Pat Collins. Sound design: Tom Morse. Production stage manager: Bonnie Brady. Performed by Eugene Barry-Hill (Andre), Doug Eskew (Ken), Kecia Lewis-Evans (Nell), Cynthia Thomas (Armelia) and Debra Walton (Charlayne).

Occupy Waller Street!

The street is an idealized version of uptown New York City in the 1920s and ‘30s. Ain’t Misbehavin’ at the Long Wharf Theatre is also a return to the brassy Broadways and Off Broadway song revues of the 1960s and ‘70s—when a passel of songs by a Ronnie Graham or a Jacques or, in this case a Fats Waller, was more than enough material with which to fashion an intimate yet exuberant ensemble show.

Nowadays, they write flimsy books around songs from numerous composers and call them jukebox musicals. I prefer box-set musicals like this one, where for variety’s sake the directors and performers are forced to creatively rework.

The Fats Waller catalogue is broad yet thin. He worked in numerous styles as a composer, and gave ingenious renditions of other writers’ material. Yet this massive talent only lived to the age of 39. He’d been gone for three decades when Richard Maltby Jr., Murray Horwitz and Arthur Faria created Ain’t Misbehavin’. Waller’s legacy had largely faded, which gave the show’s nonetheless respectful creative team license to rework the Waller magic for Broadway audiences.

Maltby and Faria are at the helm of this revival, as they have been for numerous revivals and tours of Ain’t Misbehavin’ over the years.

Long Wharf Artistic Director Gordon Edelstein’s proclamations that this production is a return to its roots—namely, the low-budget one-off cabaret revue of Fats Waller songs concocted 35 years ago for the Manhattan Theatre Club—don’t hold water (or Waller). The Long Wharf rendition doesn’t even fully resemble the show’s long-running Broadway version, where the cast’s physiques complemented each other in a more visually arresting manner and where the performers weren’t so coy about coming very close to the audience.

But to duplicate a Broadway, or even a New York cabaret club, experience at a regional theater would be the wrong behavior for Ain’t Misbehavin’.

This joints simply jump differently.

The Long Wharf has had considerable experience now in refitting musicals to the needs of its own (wide-thrust) stage and (suburban white subscriber) audience. Guys and Dolls, Man of La Mancha and Carousel couldn’t have been done at Long Wharf without being downsized, but even an already intimate show like Fantasticks was rethought for more dramatic potential.

In Ain’t Misbehavin’ at the Long Wharf, the big showy numbers such as Spreadin’ Rhythm Around can be overpowering, while most of the solo routines slyly slay you with nuance. Vaudeville staples such as jiggling bosoms and levitating bowler hats can be too broad and comic strippy for this stage, while subtle gestures such as the handing off of a reefer (and the smell of herbal cigarettes which accompanies it) can be deeply affecting. The frantic choreography in some of the ensemble numbers can be a blur, while a sedentary piece like “Black and Blue”—wisely placed after the raucous hoots “Find Out What They Like” and “Fat and Greasy” in order to calm down the room a little—wrench great harmonic feeling with nothing but vocals.

Everyone in this cast has done Ain’t Misbehavin’ elsewhere, four of them in the same 30th anniversary production in Los Angeles two years ago. For music director and onstage pianist Phillip Hall (who physically resembles Waller, at least as seen from behind while playing the piano), this is his ninth production of the show. There’s comfort in the company’s familiarity with each other, but at times there’s also that clockwork, automatic approach that can feel insincere at such close quarters. These are not perfomers we can expect to modulate their performances. They play big.

Yet it works. How could it not? It has for 30 years. Community theater productions of this show play it equally big. It’s developed its own big style. Ironically, it’s not the style of its inspiration, Fats Waller. When he said “One never knows, do one?,” it was often a murmured aside. His ad-libs and meticulously crafted one-liners could be subtle digs at his colleagues and audiences. They could be personal and precious.

Here, “One never knows…” is an oft-repeated catchphrase, carefully and louded enunciated, on the same level as the main lyrics. Nor is the piano playing as graceful as Fats’.

This is not misbehavior. It’s not wrong. The show is brilliant in how it doesn’t even pretend it is impersonating Fats Waller. Of the cast of three women, two men, pianist Phillip Hall and a six-piece backing band of local jazz players, only Hall can be said to be “doing” Fats, and even then it’s more a visual reference point, not integral to the show.

Phillip Hall, performing in the Fats Waller stride piano style, in Ain't Misbehavin' at the Long Wharf. Photo by T. Charles Erickson.

What’s integral to the show is the individual charms and talents of the starring vocal quintet. Eugene Barry-Hill and Doug Eskew dress dapper and only act slick when it’s a set-up for a joke about acting too slick. Kecia Lewis-Evans and Cynthia Thomas nail both the sassy-woman and the spurned-woman numbers. Debra Walton has the same pipsqueak impact as the littlest girl in the orphanage in the musical Annie, an adorable annoyance to the rest of the cast in a series of inspired sight gags. These are full-blown characters, despite almost no dialogue. Only one scene—a Tin Pan Alley hits montage which feels the need to explain that Waller didn’t write all these songs, (though he may well have had a few hits stolen from him)–requires a conventional spoken-word set-up. The players have clear-cut differences in temperament, vocal ranges and exhibitionist impulses.

I wish they were more physically different, too, for comedy’s sake, but maybe that’s what I’m still figuring out about how things get scaled down and spatially altered at the Long Wharf.

“Your Feet’s Too Big,” Eskew and Barry-Hill bray. Is Fats too big for Long Wharf? Not when “Squeeze Me”’s here too. Plus, any show about putting a happy, cartoon expression on the face of a Great Depression needs to be reexplored right now.

Occupy Waller Street!