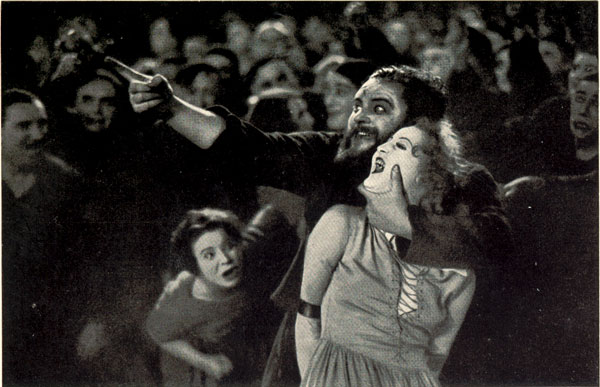

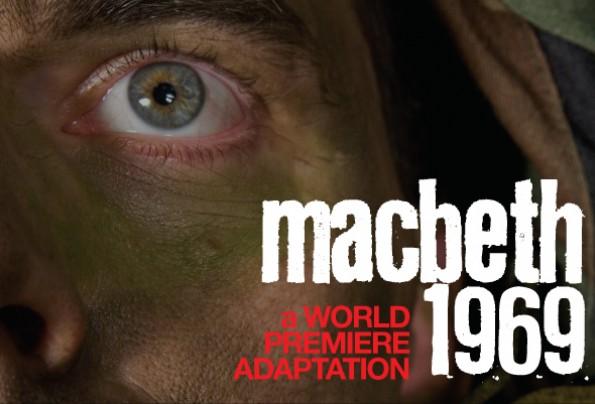

Eric Ting’s adaptation of Macbeth, which begins performances Jan. 18 at the Long Wharf Theatre, is a virtual moving forest of bold interpretative choices. Obviously, there’s the augmented title, Macbeth 1969, and the conceptual setting of the supernatural battle yarn in a Vietnam-era veteran’s hospital in the Midwestern U.S.

But there are other directorial prophesies to ponder. For instance, there are only six actors in Ting’s version, versus more than 20 in the most traditional stagings of Shakespeare’s.

For a few answers (and without wanting to indulge in any egregious spoilers), I had coffee at Book Trader with Barret O’Brien. He’s the only member of the cast who has two distinct characters—MacDuff and Banquo. The other players take multiple parts—porter, witches, whatever—and roll them into a single seamless character. The most consistent character is Macbeth, played by McKinley Belcher III, a recent graduate of the University of Southern California MFA Acting program whose credits include Tom Robinson in To Kill a Mockingbird at Bay Street Theatre and, notably, Dale Jackson in an another play about Vietnam vets, Tom Cole’s Medal of Honor Rag (at Shadowland Theatre in the Catskills).

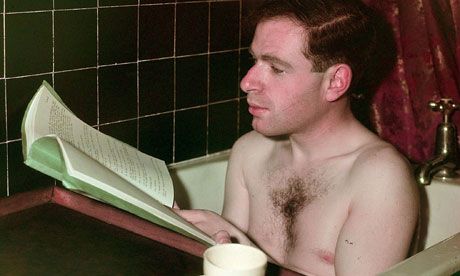

Barret O'Brien (center, in red) as Dionysus bathing Pentheus in wine and honey in Michael Donahue's 2007 Yale Summer Cabaret production of Euripides' The Bacchae. Photo by Sarah Scranton.

I was a fan of O’Brien’s work throughout his time at the Yale School of Drama, between 2007 and 2009. So, apparently, was Eric Ting. “I think he had seen me in The Bacchae,” the actor recalls. O’Brien played Dionysus in Michael Donahue’s Yale Summer Cabaret production of the Euripides tragedy, and later reteamed with Donahue to play the title role in Ibsen’s epic Peer Gynt. “We met socially after he’d seen my work,” O’Brien says. “We started talking about working together sometime. When the workshop for this came along, he asked me.”

Since he last spent time in New Haven, O’Brien has co-starred in a national tour of Ken Ludwig’s crossdressing farce Leading Ladies (produced by Montana Rep), had one of his own plays (Eating Round the Bruise) produced by the Annex Theatre in Seattle, and spent serious time writing his first novel. He also married his YSD classmate Erica Sullivan, known to Long Wharf subscribers as the title canine in Eric Ting’s production of A.R. Gurney’s Sylvia, and to Yale Rep subscribers as Hester in Oscar Wilde’s A Woman of No Importance, directed by James Bundy. The couple has a nine-month-old daughter. Following O’Brien’s Long Wharf stint, Sullivan is scheduled to play Rosalind in As You Like It for the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

Barret O'Brien (in yellow gown) as Jack in the Montana Rep tour of Ken Ludwig's The Leading Ladies.

Macbeth 1969 is the first Shakespeare play that Barret O’Brien has done since his Yale days, where verse drama takes up an entire year of the acting program.

There were a lot of logistics to work out in paring down Shakespeare’s Macbeth to a modern framework and such a small cast. “It’s like Eric took the all the text and cut and pasted it like a collage. It’s so much more complicated, getting the impressions straight in our minds,” O’Brien says. Ting, he explains, “is still changing things now, but the workshops were so major, and this time we just have the month of rehearsals. We’re able to give our input, but not like in the workshops. The script is really in a solid place. It’s like, let’s make the text we have work now.”

The actors have responded differently, and complementarily, to the demands of the adaptation. “Shirine [Babb, who assumes Lady Macbeth] has a strong classical background. She’s the ‘line guard’—it’s good to have someone in the room who’s a purist, who’s true to the text.”

Then there’s question of whether the Shakespeare plot, involving murders, witchcraft, disturbing visions and complex battle strategies, are happening in the reality of this production’s snowed-in hospital patients and nurses, or whether they’re perchance dreams.

“From my vantage point,” O’Brien says of his characters, “the things that are occurring are occurring. It’s a very realist design. It’s like a Middle American hospital in lockdown has appeared over there on Sargent Drive. There’s no musical score.”

“Shakespeare wrote this play before there were words like ‘shellshocked,’ but he understood what that meant. We’re not shying away from blood onstage. There are hints of a horror movie in this—people trapped in a hospital, snowed in, with a murder happening. It’s entertaining, not knowing what’s going to happen.”

At the same time, O’Brien insists the production is being very careful to uphold a heroic image of the American war veteran and not cheapen or stereotype it for the sake of fictional drama. “Not having served myself,” O’Brien says, “I feel a responsibility to not be glib. Theater can be glorious fun to do. To take on big topics can be very important, but also dangerous. It would be easier for us to just do the play Macbeth and set it vaguely in the ‘60s.”

There is a real-life veteran elsewhere in the cast—George Kulp, who’s playing the King role from Shakespeare’s play, rethought here as a prominent politician.

One of O’Brien’s roles, Banquo, is portrayed as a war veteran, as is his fellow soldier Macbeth. In Macbeth 1969, Banquo has “served in a firefight,” O’Brien says. “He’s suffered burns. He’s as deeply scarred physically as Macbeth is emotionally.” Macduff on the other hand, is portrayed as “not military at all. He’s a draft dodger.”

“This is a war play,” the actor concludes, “but we are trying to avoid making a statement about the war itself. If we’re making any statement, it’s that with war there are not innocents. We’re trying to reflect what Shakespeare wrote about veterans coming back from the war, and bring those elements to the forefront.”

Macbeth 1969 runs Jan. 18 through Feb. 12 at the Long Wharf Theatre, 222 Sargent Dr., New Haven.