For free in a used book shop, I stumbled upon a copy of—don’t you love how people always excessively justify how they happened to get hold of potentially pornographic products?—The Midnight Penthouse, a demure hardcover compendium of interviews, stories and yes, a smattering of “Pets” portraits, from Penthouse magazine’s first three years of publication.

Back then, Penthouse had a European air—this book has a British publisher, (Bernard Geis) and editor (the late great Peter Haining), and many of the topics are more stiff-upper-lip than stiff you-know-what.

Why mention it here? For an eye-opening yet exasperating 10-page interview interview with Peter Brook. Exasperating because the interviewer is not given a byline, and ought to be, since in the manner of the time (1967 or so), the questions are brash and argumentative. The opening gambit is: “Would you agree that the theatre is probably the most corrupt of all the traditional arts.” Brook parries it neatly: “Why, more than any of the others? I agree with the word corrupt but I don’t agree with it on a comparative basis.”

At this point in his career, Brook is still in London, trying to build two new theatre in England”: the Royal Shakespeare Theatre at the Barbican and the National Theatre. Just a few years later he’d be in France, having founded the International Center for Theatre Research. This Penthouse reprint gives no biographical background whatsoever. No byline, no intro, just a headlong chat and a “Thank you, Mr. Brook” at the end.

Still, it’s that same vagueness of time, place and priorities that makes this such a fascinating interviews. Brook isn’t pimping for his latest project, and he’s clearly already reached a level of prominence whereby he needs no introduction. His groundbreaking spate of Shakespeares occurred throughout the 1950s, his film Lord of the Flies in 1963 and his staging and filming of Marat/Sade in 1964.

Here’s a key exchange, where the interview throws Brook a curve and inserts the name of a major British radio comedian of the 1950s into a discussion of contemporary playwriting:

Penthouse: Is there an important difference, in your view, between serious theatre and theatre which merely adopts a solemn or earnest attitude—of which we have a great deal in England today.

Mr. Brook: Do we?

Penthouse: Arnold Wesker is the most outstanding example. John Osborne also has this disease of pretentiousness, seriousness in quotation marks.

Mr. Brook: The theatre is lost and trying to find itself. It really is lost. Historically the stage has to be swept clean by the theater people itself, and the writer has to give up, allow himself to be destroyed to rise again. I really think there has to be a ritual slaying of the author because the author unwittingly is the betrayer. The writer’s first instrument, his first vehicle, is the word in a sentence, and he tends to find himself led by his words, by his syntax, into a form of literary theatre. To me, there are two authors who are the spearheads of a different theatre today: one is Genet and one is Peter Weiss.

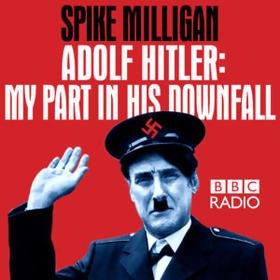

Penthouse: How about Spike Milligan?

Mr. Brook: Oh, Spike Milligan, the greatest of all theatre artists of our time. He has all the language of Shakespeare, without that one extension in depth that is at the core of all Shakespeare. Genet has something of that, but is stuck within the traditional 19th century good-writing, literary structure. Peter Weiss isn’t quite the prisoner of the literary style that Genet is. A ombination of those three theatres would give me the ideal—the poetic intensity of Genet’s vision and the free genius of Spike Milligan, a non-pompous, non-solemn, vital necessary theatre, but still an English theatre. If one said what could emerge out of the possible turning-over of England in the next 20 years, maybe such a theatre could emerge.

Around the time of this interview, the surrealist satirist Spike Milligan had in fact done some much-heralded stage work—his post-apocalyptic comedy with John Antrobus, The Bed-Sitting Room, had been a hit in 1962/63, successfully revived in 1967 and would be turned into an all-star film (which you can, and should, see “On Demand” on Netflix) in 1969. In 1964, Milligan had taken a role in an adaptation of Ivan Goncharov’s novel Oblomov, which he transformed into an improvisational tour-de-force. But Brook and Penthouse’s approval seems more general and longstanding. And given how Milligan’s The Goon Show broadcasts begat generations of stage clowns, and how some of those fans helped turn major theater festivals into stand-up comedy fests of social satire, Brook’s prediction appears to have come true.