The Yiddish King Lear

Through March 10 at the Yale Cabaret, 217 Park St., New Haven. (203) 432-1566, www.yalecabaret.org

Directed by Whitney Dibo. “Adapted, assembled and created” with Martha Kaufman and Lauren Dubowski. Set: Brian Dudkiewicz. Lights: Chris Ash. CostumesL Elivia Bovenzi. Music Director: Dana Astmann. Sound: Ken Goodwin. Assistant Sound Designer: Jacob Riley. Producer: DeDe Jacobs0Komisar. DramaturgL Lauren Dubowski. Stage ManagerL: Rob Chikar. Musicians: Gazlanim Fun Klezmer (Tess Isaac, Martha Kaufman and Elizabeth Kim). Performed by Bill DeMeritt (Reb Dovidl), Khane Leah (DeDe Jacobs-Komisar for Thursday and Saturday performances, Lauren Dubowski on Friday), Alex Trow (Tabele), Chris Bannow (Yaffe), Prema Cruz (Etele), Benjamin Fainswtein (Avrom Harif), Mamoudou Athie (Moyshe Hasid), Tanya Dan (Gitele) and Matt McCollum (Trytel).

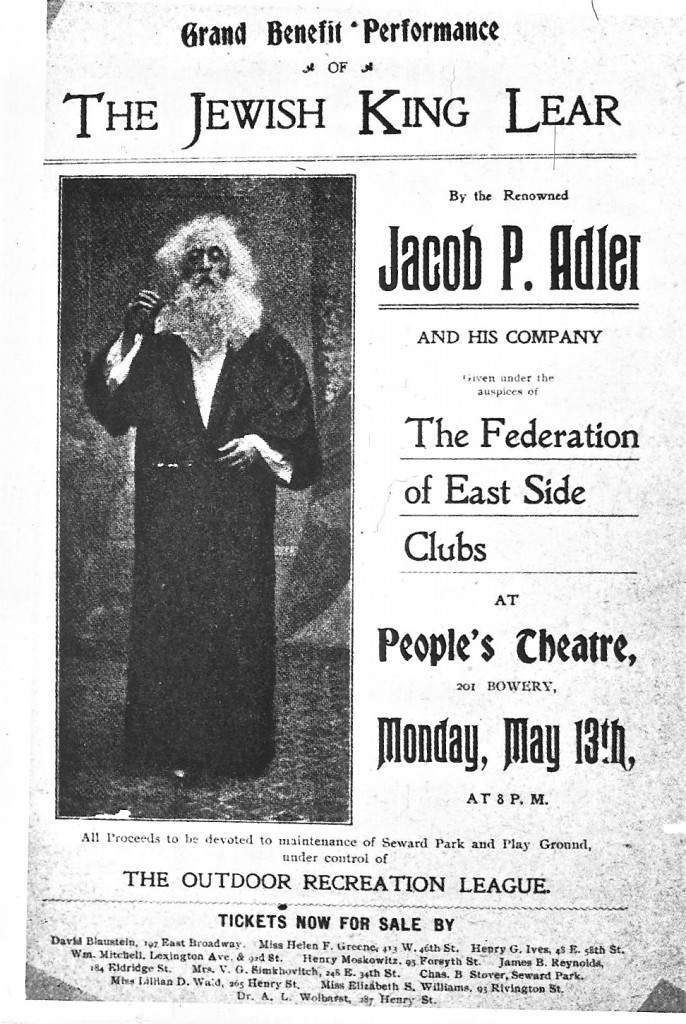

Here’s how Stefan Kanfer’s book Stardust Lost: The Triumph, Tragedy, and Mishugas of the Yiddish Theater in America (Knopf, 2006) describes the original production of Jacob Gordin’s The Yiddish King Lear, and how in rehearsals the great Yiddish theater actor Jacob Adler had to overcome the skepticism from other cast members about the merits of Gordin’s newfangled ideas.

Adler’s faith was justified. From the first reading he moved the cast away from cheap laughs and overstated melodrama. Gordin had told him all abou the naturalism of the new European drama, and Jacob strove for that kind of intense effect. …

The Yiddish Theater would never be the same. Gordin’s Lear had reached the public in a way that no spectacle, no operetta or facile melodrama could possibly have done.

The Yale Cabaret has now taken the daring step of restoring the cheap laughs and overstated melodrama. They play Gordin’s script broadly and cut it so that the plot into something approaching Grand Guignol. They keep all the action to one dining-room set, excising some famous scenes set on the mean streets and in a synagogue. They enlist a live three-piece Klezmer band for a lively soundtrack and sound effects. They’ve added plants in the audience to act as aggressively involved groundlings, commenting excitedly on the action as it occurs and punching the laughs prompted by the many insult jokes in the production (“At least I can grow a beard!”). There is a Purim Play-within-a-play, and that is even more overacted.

By doing so, they suggest that this is what the Yiddish theater in late 19th century New York must have been like.

I have my doubts about that, but I can also appreciate the risks and experimental assaults involved here.

Mocking the old-fashioned dynamics of an old-fashioned script may not seem daring, but I say it is because of how easily this style parody could slip into an area which also makes fun of the ethnic culture associated with the drama.

Yet the Cabaret cast is largely able to stick with theatrical stereotypes—the Jon Lovitz “Master Thespian” school of overacting—without overdoing the ethnic stereotypes at the same time. It’s a fine line, and a funny one.

Still, Jacob Gordin’s 1892 script does not fare well in this production. It’s done as a heavy handed imitation of the naturalist and modernist styles then sweeping Europe, and the merriment, by extension, mocks Gordin’s audiences by suggesting that it would have been hard for anyone to ever have taken this drama seriously. In fact, the original script is no more ridiculous than many earnest adaptations of Shakespearean themes. Not technically an update or a modern revision, it’s a contemporary drama in which the patriarch of a Jewish family does a series of stubborn and foolish things, enduring the consequences and finally earning a happy ending. Gordin even has one of the characters tell the lead character that he’s been behaving exactly like King Lear, which is sort of a leap for this sort of thing: nobody told Steve Martin in Roxanne that he was acting just like Cyrano de Bergerac.

In the role originated by Jacob Adler (father of Luther Adler and Stella Adler, who as actors and teachers themselves carried some of Jacob’s acting techniques straight through the 20th century), Bill DeMeritt is less inclined than some of his castmates to fall into style parody and easy laughs. He plays the tragedy straight, which in this largely comical context becomes parodic in a self-serious way. The rest of the cast shorthand their characters to drunken useless husbands (Mamoudou Athie, nursing bottle after bottle), shrewish wives (Prema Cruz, as Etele, who’s both Regan and Goneril at once) and spotlessly pure young lovers (Alex Trow, in the Cordelia mold).

I’m going to wrestle with this one for a while. I’ve never thought it fair to poke fun at older theater conventions simply because they engaged the audience so viscerally.

Yes, audiences yelled back at theater actors a century ago, and shouted out the plot points in advance. Do we not scream the same way at our televisions now?

There is an undercurrent of sympathy in this production—the supporting cast of those not playing the actors but the audience members and backstage staff of the Yiddish theater relate personal stories of how much going to the theater meant to them in that age of sweatshops and segregation. The statements are drawn from interviews done by Nahma Sandrow at the Workmen’s Circle Home for the Aged.

But the sensitivity, strangely, doesn’t extend to The Yiddish King Lear itself, a play that had a hearty life in community theaters for decades after Gordin wrote it and which is considered a milestone of the Yiddish theater movement. Ultimately, it’s no harder to do a cheesy, overacted, funny-on-purpose production of The Yiddish King Lear than it would be to do one of Shakespeare’s King Lear itself. I like a good laugh as much as the next guy, and there are plenty to be had here, but I guess I’m still groping for the point.