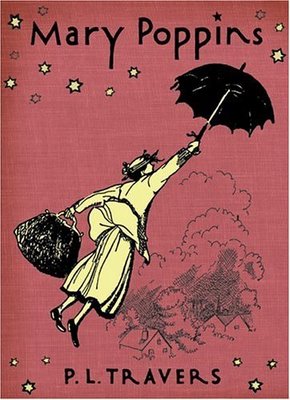

The cast of February House, the new musical premiering at the Long Wharf Theatre prior to a run at New York's Public Theatre. Photo by T. Charles Erickson.

February House

World premiere production. Through March 18 at Long Wharf Stage II, 222 Sargent Dr., New Haven. (203) 787-4282.

Book by Seth Bockley. Music & lyrics by Gabriel Kahane. Directed by Davis McCallum. Choreographed by Danny Mefford. Musical Direction by Andy Broson. Orchestrations by Gabriel Kahane. Set Design by Riccardo Hernandez. Costume Design by Jess Goldstein. Lighting Design by Mark Barton. Sound Design by Leon Rothenberg. Vocal/Dialect Coach: Deborah Hecht. Production Stage Manager: Cole Bonenberger. Cast: Julian Fleischer (George Davis), Kristen Sieh (Carson McCullers), Erik Lochtefeld (W.H. Auden ), A.J. Shively

Like a lot of musical theater geeks, I am currently in the thrall of TV’s Smash, which fictionally follows the development of a new musical based on the life of Marilyn Monroe. So you have to chuckle, imagining the conversations which begat February House. If the inspiration for the show were placed in the grandiose Broadway hyperconcept realm of Smash—environs just a subway ride away from New York’s Public Theater, where February House will play once its developmental shakedown at Loong Wharf is done.

“You know what?,” a Smash character could say. “Somebody really should make a musical about W.H. Auden. I’d see that.”

“But who would play Chester Kallman?”

At the same time, February House has some uncanny things in common with Smash’s made-up Marilyn musical. It’s set in the mid-‘40s, and shows the state of the New York literary and theatrical world a decade before Marilyn came there fro the method acting and the Arthur Miller. It’s a era which is shifting from smart-set magazines and romanticism to intellectual journals and new forms of expression. February House, a boarding house in Brooklyn, becomes the gathering spot for some world-changing artists, but the communal experience plays out a lot differently than it does in, say, Rent.

February House is homey, comfortable, conversational, intent on intimacy, on knocking its real-life characters down to human size. Its first act builds a sort of fantasy around the prospect of several world-class writers and musicians sharing a home. There are high hopes amid the humorous personality clashes, and a chance for solace and contentment in a place where these artists (most of whom are homosexuals, enraptured by the prospect of a home without closets) can be themselves.

Stephanie Hayes as Erika Mann, Kristen Sieh as Carson McCullers and Erik Lochtefeld as W.H. Auden in the musical Februrary House at Long Wharf Theatre. Photo by T. Charles Erickson.

The latest episode of Smash had a number about Marilyn and Joe Dimaggio just wanting a quiet marriage in an out-of-the-way location. February House provides the same theme, only the couples are poets Auden and Kallman, the composer Benjamin Britten and his muse Peter Pears, novelist Carson McCullers and her estranged husband Reeves, and seductive wild cards Erika Mann (Thomas Mann’s politicized actress daughter) and the stripper Gypsy Rose Lee (who, yes, has already had a musical done about her, and settles for supporting-character sass here).

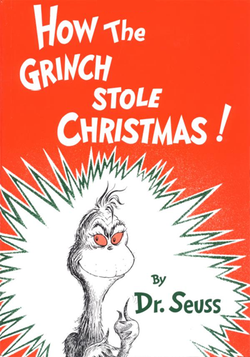

Quite the ensemble, but the moist heartwarming (hearthwarming?) aspect of February House is how attentive it is to its title character. (The musical is inspired by a non-fiction chronicle of Feburary House, aka 7 Middagh Street in Brooklyn, publishedin 2005 by Sherill Tippins, who’s been consulting on this production.) The key ensemble scenes all have to do with boarding house exasperations such as leaky pipes, vermin, unpaid utility bills and that common annoyance of trying to write your next novel when a bunch of Brits are composing an opera based on Paul Bunyan in the parlor.

The house rules. It gives the show structure, context and an evenhandedness when juggling the lives of a host of disparate big-name writers at fascinating transitional times in their long careers. The second act delves deeper into the actual historical circumstances of the house’s inhabitants, and turns February House into a show that no longer about the ability to create and commune but the need to sustain one’s dreams and careers and passions.

W.H. Auden (in a miraculously measured portrayal by Erik Lochtefeld, bright and emotional without descending into parodic or overly grave) is defensive about how overtly political to make his poetry during the mounting international concerns of World War II; meanwhile, he’s caught in a passionate relationship to the much younger Kallman (a sparky male ingénue turn by A.J. Shively), who can’t match Auden’s commitment to their illicit marriage.

Auden’s also writing the libretto for Benjamin Britten’s misfire of a folk opera, Paul Bunyan, a project the composer (and his joined-at-the-hip lover, Peter Pears) hopes will bring some commercial cachet to his critical acclaim.

Carson McCullers is in between bouts with Reeves, and is the house’s most gushing fount of enthusiasm; tuning her outrageous Southern accent so it registers as both otherworldly and dwon-homey, Kristen Sieh singlehandedly creates a new mythology for McCullers. She’s no longer the morose Southern realist misfit; she’s a happy vacationer, ingratiating herself to the other farflung tenants. McCullers finds a special connection with Erika Mann, whom recent Yale School of Drama grad Stephanie Hayes plays as a curt German cipher who enjoys her own quirks and passions even while berating those of others. Mann becomes the conscience of the play, history-wise at least, since she’s the most consciously activist about the war. But she also handles a comic relief interloper element, at least until a certain renowned ecdysiast shows up at the end of the first act.

Kacie Sheik as Gypsy Rose Lee in February House. Photo by T. Charles Erickson.

Gypsy Rose Lee, a mid-show breath of bump-and-grind courtesy of Kacie Shiek (Jeanie from the Public Theatre revival of Hair) gets to deliver a delightful literary striptease variation on Cole Porter’s “Brush Up Your Shakespeare”:

Jewelry sure won’t do the trick

Red fox fur just makes me sick

But offer me a list of your academic laurels

And soon, dear mister,

You’ll make me weak in the patella

You woo this sister

With a disquisition on Melville’s novella

Today we play a different kind of game

A fella’s gotta win his gal with a little brain.

Such lighthearted moments aren’t limited to Lee’s cooing, Mann’s imperiousness, and McCullers’ Southern charm. Britten and Pears (bespectacled Stanley Bahorek and cravat-clad Ken Barnett) are presented as a whimsical English Music Hall double act, getting their own Gilbert & Sullivan-styled patter song, “Shall We Live Here” in the first act, then a scratch-choreographed ode to odious bedbugs, and another stand-alone set piece where Chester Kallman instructs these stiff, mannered gentlemen on how to loosen up for a New York society party. If three such comic digressions, all based around the same stuffy-Brit stereotypes, seems too much, well, they’re equally funny and cutting any one of them would be callous.

Through it all, February House serves as a solace, a workspace and a shelter from the encroaching storms of world events (the time is 1940-41, when the U.S. has yet to enter the war) and the turmoil of surviving as serious artists.

Riccardo Hernandez’s ingenious set design doesn’t impose “house” on the play the way another homebound new musical which had its premiere in New Haven, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, did at Yale Rep last year. The set is open-ended—open-backed, even, with a pit at the back of the stage into which characters step when leaving for the outside world. The actors interact with props and each other rather than with whole rooms.

Julian Fleisher, Kristen Sieh, Stephanie Hayes and Erik Lochtefeld in February, filling up Riccardo Hernandez's purposefully sparse set design. Photo by T. Charles Erickson.

The house is embodied not with interior design but with an upstanding, uproarious, upholstered performance by Julian Fleisher as the real-world February House’s instigator, editor George Davis. It’s a wonderful stroke of inspired casting. Fleisher’s a modern Renaissance man himself, who does cabaret acts, fronts a swing band, writes, produces records and appeared as Cat in last year’s cult-hit musical version of Neil Gaiman’s Coraline. He shares the real George Davis’ understanding of how artists are nurtured and cared for, while building a big role for himself as the promoter of all this creativity in others.

In fact, when the plot falters at all, it’s due to the presumption that we care about the next chapters in some of these storied artists’ lives more than we do about others. The show ends with a powerful solo turn by Julian Fleischer, a lament to his departing housemates eloquently titled “Foundation Breathes a Loss.” Fleisher ends it with a bittersweet flourish reminiscent of Liza Minnelli doing the title number in Cabaret. But that climactic moment is followed with a downbeat exchange between Davis and Carson McCullers, when the show’s crying out for a full-cast, full-house closing number. McCullers, especially as animated by Kristen Sieh, may indeed be the most deeply drawn and appealing of the February House tenants, but she shouldn’t trump the landlord or the house itself.

The show’s uneven, overwrought conclusion is a concern mainly in that it can alter audience’s at the last minute, perhaps making them forget what a finely tuned, carefully emotionally balanced affair most of this musical has been. Wunderkind composert Gabriel Kahane’s score, and especially the clever wordplay in his lyrics, blend seamlessly into Seth Bockley’s community-minded script. Despite often festering in their distinct personal dramas on opposite sides of the stage, February House’ characters are linked stylistically and harmonically, blending their traumas and celebrations in elaborately arranged songs. As Mann and McCullers, Hayes and Sieh begin a beautiful road song duet, “Wanderlust,” in which the agitator invites the novelist to accompany her on a speaking tour. Just a few verses in, they’re joined by W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman, debating their own, less expansive dreams of escape. It’s a risky, complex four-part arrangement that ends up taking the whole housebound show to a new level of drama, at the perfect place in the first act. Director Davis McCallum matches the intricacy of the score with a staging that meshes the characters’ movements without crowding the rather small, wide playing area.

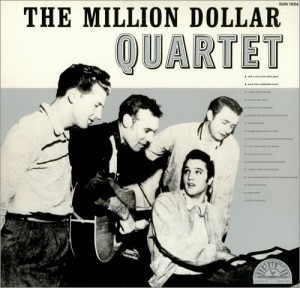

Going back to Smash-consciousness, what really needs to be said is that February House may strike some observers like a pop chamber piece, a precious work of musicalized literary biography. That’s as unfair a characterization as it would be to say Auden’s poetry can’t speak to the masses, or that Britten’s compositions are too remote and modernist (assertions the artists wrestle with within this show). Kahane has pop records on his resume, and some songs here (especially those Britten & Pears routines) leap out of left field, but this is nonetheless a steady and fluid and overpowering score, languid in its quiet metronomic repetitions and inspired in its basic yet full musical arrangements. It’s a consistent style that Britten himself could appreciate. Mirroring the minimalist needs of the creative characters being portrayed, the music is knocked down to bare essentials: just the vocalists and the two-piece onstage band of Andy Boroson (whose piano doubles as an element of the set, the grand piano brought to the house for Britten to play) and Andy Stack (whose guitar strums are weighty, but who truly distinguishes himself on banjo, making that instrument much more than convenient shorthand for Carson McCullers’ Southerness).

There’s so much that’s right about February House, and so many potential pitfalls (the sprawling environment, the jarring personalities, some appalling real-life episodes which came after the events of this show, the degree to which the war and other outside-world events should be allowed to impinge on the household). There are breakthrough performances by Julian Fleisher as George Davis, Kristen Sieh as Carson McCullers and Erik Lochtefeld as W.H. Auden, three character-actor types who seem the most unlikely of New York musical theater lead players yet command the stage as if they were, well, Marilyn Monroe and Joe Dimaggio. February House is our own little regional theater, Off Broadway, academically sound Smash.