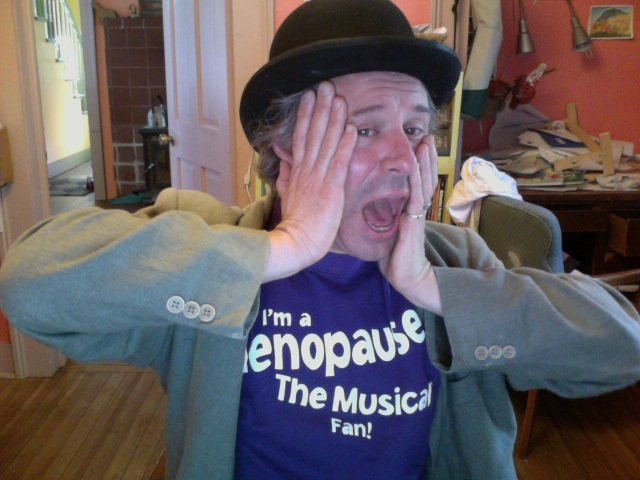

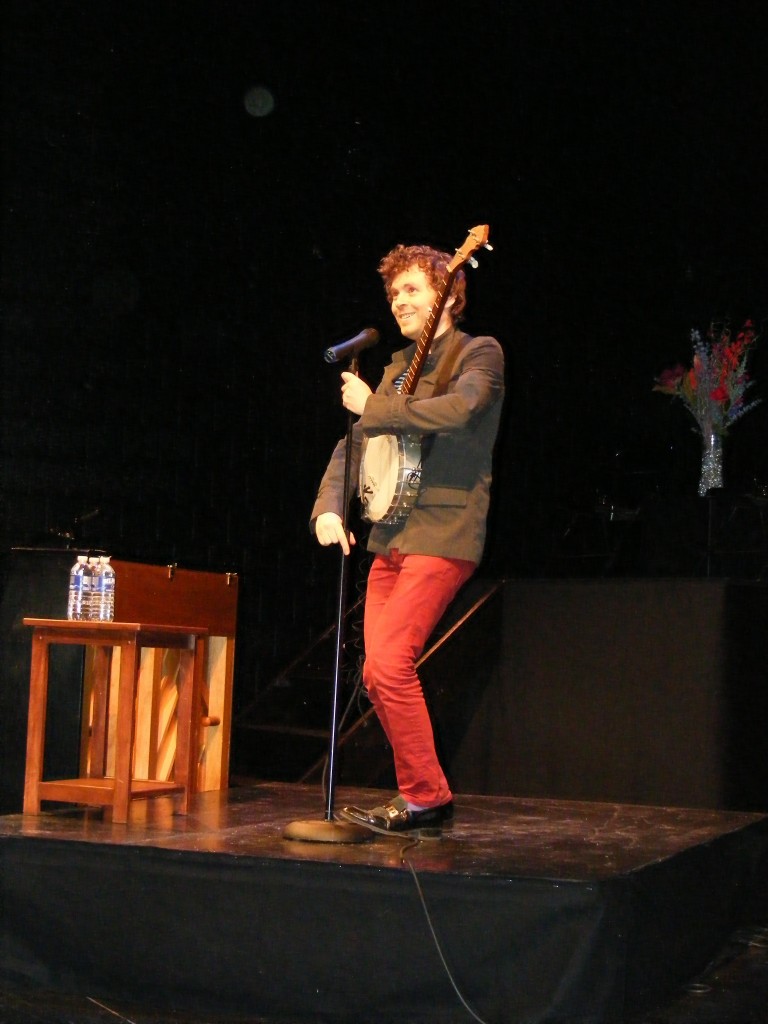

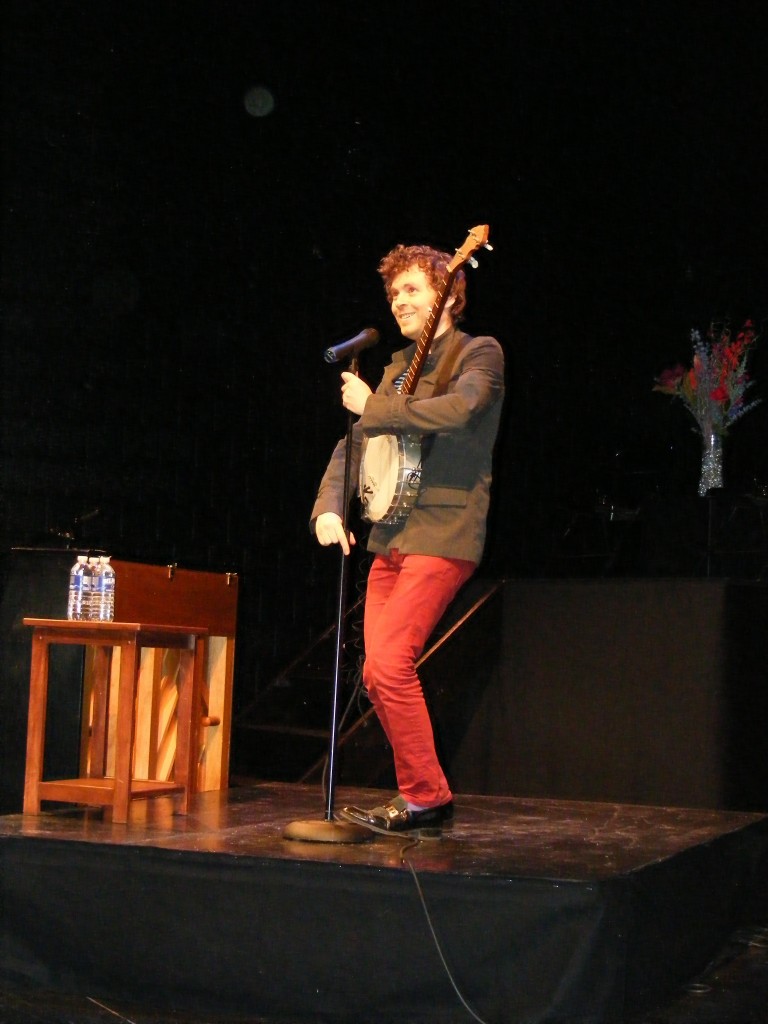

GABRIEL KAHANE PERFORMING AT THE LONG WHARF THEATRE’S 2011-12 SEASON ANNOUNCEMENT. PHOTO COURTESY OF LONG WHARF THEATRE.

The Long Wharf Theater’s 2011-12 season looks pretty good on paper—two musicals, a Shakespeare, a Christmas show, a supernatural comedy set in the 1950s and a dark human drama set in the ’40, plus one show still to be announced.

But it felt even better Monday night, hearing it announced and described by Long Wharf artistic director Gordon Edelstein, then actually being able experience pieces of two of the shows firsthand.

If singer/songwriter Gabriel Kahane, who got both indie icon Sufjan Stevens and bluegrass virtuoso Chris Thile to appear on his first pop album, and who is renowned in the neo-classical scene as the composer of the quirky web-savvy piece craigslistlieder, were to make an unexpected appearance at a club like The Space or Café Nine, playing three brand new songs, you can imagine the gleeful frenzy.

Well, yesterday, Kahane did that trick at the Long Wharf, where it was proudly revealed that the theater was a co-producer of his new musical February House, already announced as part of next season at the New York Public Theatre.

The Long Wharf actually gets February House first Feb. 15-March 18, 2012. (It moves to New York in May/June.) The relatively intimate show, which reportedly has a cast of eight and a five-piece band, will be staged in Long Wharf’s smaller Stage II venue—same place where Kahane premiered three of February House’s songs last night.

The musical’s based on the real-life occasion when some of the leading cultural lights of the first half of the 20th century—poet W.H. Auden, novelist Carson McCullers, composer Benjamin Britten and stripper Gypsy Rose Lee—became housemates in Brooklyn Heights due to the coaxing of erstwhile Harper’s Bazaar editor George Davis. The musical February House is based on Sherill Tippin’s 2005 book of the same name; Kahane told me Tippin passed on boxes and boxes of research materials to him. Kahane’s credit for the show reads “songs and lyrics,” while Seth Bockley—the Chicago-based playwright known for thinking visually and working well with designers and on “devised” ensemble works—is doing the libretto. Davis McCallum will direct.

For the Long Wharf festivities, Kahane did three numbers—two on banjo, one on piano. First he plucked a catchy riff for a confessional song sung in the show by the Carson McCullers character, with the refrain “My communion at Coney Island.” Then he sat at the piano for a rousing ensemble number about George Davis convincing the artists and their lovers to all set up housekeeping together. The recurring phrase this time was “comes together”: “A room comes together,” “a house comes together.” Then he hopped across the stage and picked up the banjo again, for a wistful ballad, a lullaby to the house in fact: “Sing goodnight to the boarding house.”

Kahane has the ability to work in many styles. These were songs, as you’d find in a club set. No hints of heavy arrangements, and the lyrics shone through. A memorable appetite-whetting preview of a show we now have to wait eight months to see.

February House falls right in the middle of the Long Wharf 2011-12 season. Here’s the rest of it:

September 14 through October 16 is The TBA slot. A press release boasts that it will be “a work from a major playwright.” Edelstein told me that he won’t be directing it, if that’s any kind of clue. It’s also happening at Stage II, not on the mainstage.

Oct. 26 through November 20: Ain’t Misbehavin’.

That surefire late-1970s revue of 1930s Fats Waller songs, the Broadway hit which, for better or worse, led off the whole “jukebox musical” craze. Edelstein was able to put a creative spin on this project and make it seem like more than a crowdpleasing commercial consideration: He’s enticed Richard Maltby Jr., who created the show with Murray Horwitz and who directed its original production at the Manhattan Theatre Club, to bring it back to those cabaret-scaled roots. Edelstein noted that Maltby has a strong prior relationship with Long Wharf

Vocalist Julia Lima and pianist Billy McDaniel were enlisted to do two numbers from the show at Monday’s announcement: “Handful of Keys” and “Keepin’ Out of Mischief Now.” Those numbers both fall safely between the show’s blues and swing extremes; you’ll have to wait until October for sultry stuff like “The Viper’s Drag” or rousers like “The Joint is Jumpin’.”

December 7 through 30: It’s a Wonderful Life—A Live Radio Play.

Long Wharf’s attempt to build a hardy seasonal perennial along the lines of A Christmas Carol at Hartford Stage, or A Christmas Carol at the Shubert, or A Christmas Carol at… Well, we should just be thankful that the Long Wharf has avoided doing another Christmas Carol. The theater’s previous holiday offerings have ranged from the world premiere of Paula Vogel’s grand historical pageant A Civil War Christmas to the wacky one-person shows Sister’s Christmas Catechism and My Mother’s Italian, My Father’s Jewish and I’m Home for the Holidays.

This adaptation of the heartwarming Jimmy Stewart movie was wrought by Bridgeport-based playwright Joe Landry. It played every year at the Stamford Center for the Arts’ Rich Forum while that was still an active theater, and has since been done at regional theaters from Rhode Island to California.

January 18 through February 12: Macbeth 1969: Shakespeare’s militaristic tragedy reconceived for the Vietnam War-era America by wunderkind Long Wharf Associate Artistic Director Eric Ting. Macbeth and the other soldiers are returning veterans, the weird sisters are VA hospital nurses and a total cast of six encompasses all the emotional turmoil and dreams of Shakespeare’s play.

Following the aforementioned February House (which plays February 15 through March 18 in Stage II), spring appears via the romantic comedy Bell, Book and Candle. The time is right for a revival of this skillfully written romantic comedy by John Van Druten, the prolific British playwright whose straight-play dramatization of Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories became the basis of the musical Cabaret and whose other mid-20th century hits include The Voice of the Turtle and I Remember Mama. Bell, Book and Candle has been in the air lately: Ernie Kovacs, who has scene-stealing moments in the film version of the play, has just been celebrated with a major box set of his TV work, and Sol Saks, who created the famous 1960s TV series inspired by Bell, Book & Candle—Bewitched, starring Elizabeth Montgomery, Agnes Moorhead and interchangeable Darrins—died last week. The TV series was a breezy delight, but the play is more attuned to changing times, especially in its characterization of witches as a feared and misunderstood yet powerful and committed segment of society. In his description of the play Monday, Edelstein astutely labeled it “a romance between a witch and, shall we say, a straight person.” Long Wharf will present the co-production first, March 7 through April 1; Hartford Stage gets it April 4-29.

The Long Wharf 2011-12 slate ends with the only show to be personally directed by artistic director Gordon Edelstein this season. (He’s often done two a season.) It has the potential to be a real cross-generational crowdpleaser, one which could draw in both the historical-novel book club readers and the comic book fanboys.

It’s Sophie’s Choice, starring Carla Gugino.

In discussing the project on Monday, Edelstein mentioned how the famous 1982 film version skewed William Styron’s massive novel into the story of its titular immigrant heroine, when the full novel is more of a coming-of-age story for the young male protagonist Stingo. Acknowledging the darkness and depression in the tale, and the plot’s connection to Styron’s own time in New York as a young man, Edelstein characterized it as “Dante’s Inferno” for Stingo/Styron, with Sophie as “his Beatrice.”

That angle is apparently restored in the new script version by David Rintels (best known for penning the one-man show Clarence Darrown, which became a sturdy touring vehicle for Henry Fonda and Leslie Nielsen). Rintels was given the rights to adapt the book by Styron himself, shortly before the novelist died last year.

It’s the first time Sophie’s Choice has been adapted as a play, though a decade ago Nicholas Maw made it into an opera (first done in London in 2002, and given its American premiere in 2006). The Long Wharf production is a world premiere, and will be workshopped in New York before coming to New Haven for further rehearsals and its April 2012 opening.

Edelstein noted how physically attracted Stingo is to Sophie in the book. That’s part of the genius in casting Carla Gugino, pin-up passion of countless teen boys who know her as Sally Jupiter (aka Silk Spectre) in the movie version of Watchmen, or as the naked gun-toting broad Lucille roused out of bed by Mickey Rourke in Sin City, or as the action-packed U.S. Marshall heroine of the TV series Karen Sisco, or as the Spy Mom in the Spy Kids movies, or as Vincent Chase’s Hollywood agent Amanda on Entourage. Here’s a Sophie who’s done movies with Robert DeNiro and Forest Whitaker, and who’s posed near-nude for lad mags.

Gugino’s also one of those actresses who gained fans early in her career by being noticeable as more than just a pretty face, in a slew of thankless or underwritten roles. She was Michael J. Fox’s romantic interest for the entire first season of Spin City, Dr. Gina Simon on Chicago Hope and Sydney, the affair-ridden wife of Ian St. James on the prime-time soap Falcon Crest. She has a history of smartening up every character she plays. Her theater resume is less expansive than her screen one, but no less impressive: Tennessee Williams’ Suddenly Last Summer and Arthur Miller’s After the Fall, both for the Roundabout Theatre Company, and a Tony nomination for the Broadway production of O’Neill’s Desire Under the Elms (which transferred from Chicago’s Goodman Theater). The range of projects she involves herself in, from blockbuster comedies (Night at the Museum) to kiddie sequels (Homeward Bound 2) to cult films (The Singing Detective) to Sundance indies and mockumentaries, is dazzling. Sophie’s Choice is just another bold and exciting choice in Carla Gugino’s admirably unpredictable and exhilarating career.

Edelstein noted the geographical and historical links between February House (set in Brooklyn Heights, New York, in the early 1940s) and Sophie’s Choice (Brooklyn, 1946). He could have added that Ain’t Misbehavin’ is only a few dozen miles a decade or so further down the road (its score emanates from the Harlem Renaissance of the late 1920s/early 1930s) and that Bell, Book and Candle is also a New York piece, set in Greenwich Village in the late 1950s. Yet this is nonetheless a far-flung, delicately balanced season of thrills, chills, pathos and cheeriness that Connecticut audiences should be advised to flock to.

The Long Wharf hasn’t always done these season-announcement presentations. The presence of Gabriel Kahane made me flash back to an event touting the 2002-03 season, which included actors singing Duncan Shiek songs from the musical Spring Awakening, which Long Wharf ending up not doing after all. If any of THESE shows don’t happen, I’ll be weeping. Yes, even It’s a Wonderful Life—Eric Ting’s directing it, right before he does Macbeth!

GORDON EDELSTEIN ANNOUNCING THE 2011-12 LONG WHARF SEASON. PHOTO COURTESY OF LONG WHARF THEATRE.