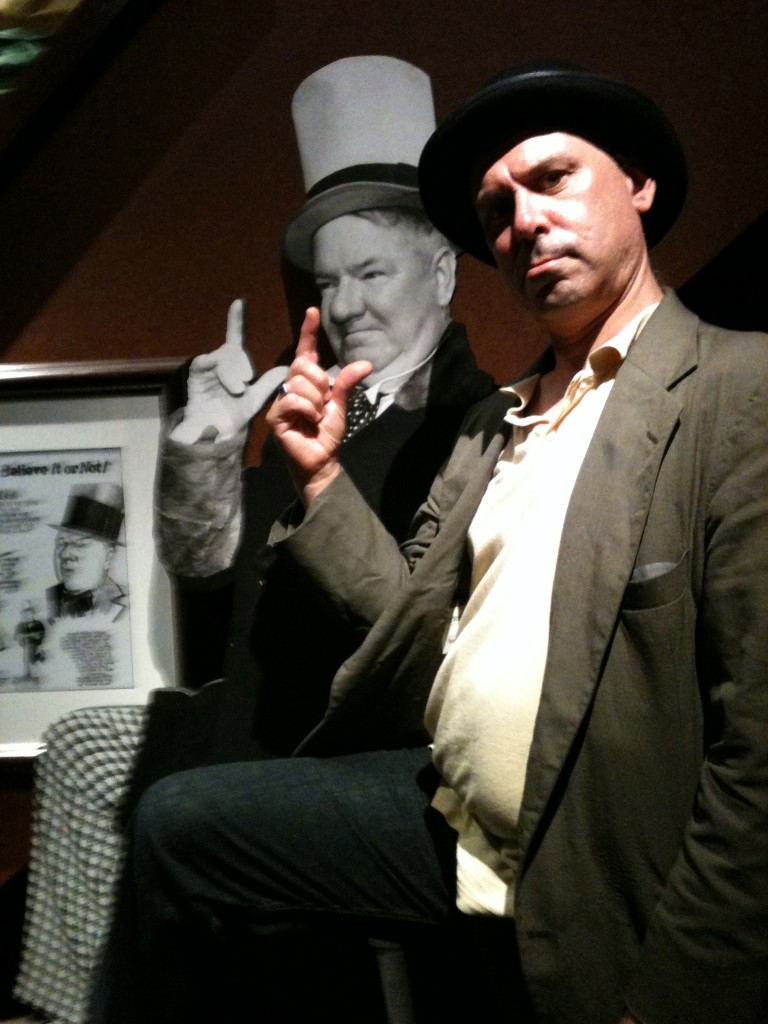

My daughter Mabel snapped this shot of me alongside a lifesize cut-out of W.C. Fields at the Ripley’s Believe It Or Not museum in Times Square. I’d planned to bring the girls to their first Broadway show that day (we were considering Mamma Mia!) but we ended up spending the afternoon at Ripley’s instead.

Why is W.C. Fields a Believe It Or Not icon? I don’t recall. Perhaps it’s all the juggling he did. Or all the drinking.

Believe it, Arnott!

Who’s in the Header Photo?

The Summer Youth Theatre Hamlet Review

The curtain call of the first performance of Summer Youth Theatre's "Shake-It-Up Shakespeare" adaptation of Hamlet, at Long Wharf Stage II. Snapped furtively on my iPhone.

Hamlet

By William Shakespeare. Directed by Annie DiMartino. Musical Director: Carol Taubl. Performed by Sam Taubl (Hamlet), Erik Van Eck (Claudius), Jane Logan (Gertrude), Ryan Ronan (Polonius), Jessica Coppola (Ophelia), James Taubl (Laertes), Jack Taubl (The Ghost), Jeremiah Taubl (Horatio), Maris Sullivan (Rosenkrantz), Kira Topalian (Guildenstern), Anthony Rockford (Grave Digger), Nina Dicker (First Player), Danielle Bonanno (Second Player), Bowen Kirkwood (Messenger), Chelsea Dacey (Lord) and Dawn Williams.

Final performance 7 p.m. Friday, Aug. 26 at Long Wharf Stage II, 222 Sargent Dr., New Haven. (203) 787-4282, longwharf.org. Playing in repertory with Threads of a Spider Web (7 p.m. Aug. 25 & 27).

Strangely, this is not the first time I’ve heard “Bohemian Rhapsody” performed live in its entirety by high school students as part of a summer theater program in Long Wharf’s Stage II space. The last time was over 15 years ago. There is nothing new under the sun.

On the other hand, it’s the first time I’ve heard “Bohemian Rhapsody” done by the Players in Hamlet, rewritten to fuel the plot thus:

Mama, I’ve just killed a man

Poured some poison in his head…

And I can categorically state that I’ve never before heard the Ghost of Hamlet’s Father intone “I Used to Rule the World” a la Coldplay. That same band’s “42” is also sung, along with a couple songs each by Evanescence and Death Cab for Cutie, the June Carter Cash/Merle Kilgore classic “Ring of Fire,” The Spice Girls’ “Wannabe” (delivered here by the young women playing Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern), the Jack’s Mannequin dirge “Dark Blue” (its sea imagery underscoring Hamlet’s fraught ship voyage to England) and Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” (which here provides a play-ending soliloquoy for Horatio).

Oh, and the stomps and claps of another Queen song (the band, I mean, not Gertrude), “We Will Rock You,” punctuate the culminating duel of Hamlet and Laertes , who snarl the “Buddy, you’re a…” lyrics while violently stabbing at each other with violin and cello bows.

I don’t mean to make The Long Wharf Theatre’s Summer Youth Theatre Series production of Hamlet sound campy or forced. The show’s played straight and somber, shadowy and sincere. The teen actors show considerable talent. What’s most impressive is how fluidly this rock-theater rendition of Hamlet plays.

Impressive, though not exactly a surprise. There’s a rich tradition of classics being studded with modern music, dating back to at least the 1960s, though I’m used to it being more of a college phenomenon than a high school one. At Harvard University in the 1980s alone, there was Bill Rauch’s Medea/Macbeth/Cinderella (which brought in country & western songs along with Rodgers & Hammerstein) in 1984 and Alek Keshishian’s Wuthering Heights (subtitled “A Pop Myth” and infused with songs by Madonna, Kate Bush, Sting and others) in 1986.

The Summer Youth Theatre’s Hamlet features complete musical theater performances, integrated into the Shakespeare text with the accompaniment of an onstage band of keyboards, percussion, electric bass and a hard-working string section. Several of the actors double as musicians.

Of the 18 kids in the cast, five were in a similarly styled Shake-It-Up Shakespeare production of Taming of the Shrew last year. Three of those five—Jack, James and Jeremiah Taubl—are offspring of the Summer Youth Theatre’s musical director, Carol Taubl. This year they’re joined by their older brother Jack, so that various Taubls handle the roles Laertes, Horatio and both Hamlets (prince and ghostly dad),. Whatever those casting decisions may lack in, say, variety (those Taubl boys all look frighteningly alike; two of them are twins) may be gained back in the sheer delight the brothers seem to have in pummeling each other in the fight scenes.

There’s the usual youth-theater complication of teens playing the parents of other teens. The universal code of how older men are supposed to look—dour expressions and business suits—is applied for Claudius (Erik Van Eck) and the Ghost (Jack Taubl). As the dead characters in the play mount up, they all go sit underneath the high platform which serves as Elsinore’s tower. To older viewers like myself, the sight of nine teens brooding in a corner resembles a detention room scenario, or perhaps the “jail” in a game of Kick the Can.

But strong examples of creative problem-solving throughout this show outweigh such understandable and unavoidable obstacles as teens happening to look their age. Mostly, what happens when you strip down the stage to black-box essentials, stick a musical ensemble at the back of it, and insert pop songs into the soliloquoies and swordfights, is that the key moments of the play are cleanly delineated and plainly pronounced. The result is simply good scenework, an honest and brisk interactions between focused actors handling the Shakespearean scansion remarkably well.

Hamlet premiered last night, and has its second and final performance Friday, Aug. 26 at 7 p.m. A whole other Summer Youth Theatre series show, Threads of a Spider Web, opens tonight (Thursday) at 7 p.m. and has its second performance Saturday. Threads utilizes the same cast, stage set-up and theater/music mix as Hamlet, this time in service of a compendium of poems by Shakespeare, Dickenson, Wordsworth and Coleridge, informing a narrative about a family coping with the loss of loved ones in a car crash.

Annie DiMartino who adapted Hamlet, created Threads of a Spider Web and directed both shows, explained to me in a phone interview last month that the Summer Youth Theatre Series is “not a class. There’s no tuition. The kids really do audition.” There’ve been 15 hours of rehearsal a week since mid-July.

DiMartino incorporated modern pop music into the plays so as to give the young actors a quick handle on their characters’ motivations, and to further their input by having more mutural reference points. “They’d say ‘Oh, I love that song,’ and explore the connections. Like last year, when we piloted this project, and this year, doing two shows, I’m just awed.”

Despite consistent themes of death and despair, DiMartino considers both showsto be “totally appropriate for a youth ensemble. In cutting Hamlet (which still runs two and a half hours, what with all those songs in there), she says she aimed to “cut out the political commentary, and made it about family: Hamlet, Gertrude and Claudius. Hamlet is very dark, with the ghost, revenge, death. Threads of a Spider Web is more hopeful. It’s a nice balance for the cast.”

A Bohemian rhapsody, if you will.

Leiber & Stoller & Brecht & Weill

Jerry Leiber (who died yesterday) and Mike Stoller deserve more respect from the theater world than just as the songwriters behind one of the better jukebox musicals.

Man, even the Leiber obit in Playbill Online sells the guy short, concentrating mainly on Smokey Joe’s Cafe while mentioning in passing that Stoller co-wrote the score for The People in the Picture and that Leiber/Stoller songs figured in jukebox or revue shows such as Dancin’, Rock ‘n’ Roll! The First 5000 Years Ring of Fire, All Shook Up, the Peggy Lee show Peg and of course Million Dollar Quartet.

Read their amazing tag-team autobiography Hound Dog and you’ll find Leiber and Stoller enthralled by live theater at a young age. When not writing million-selling pop hits, they spent untold hours trying to crack the musical theater firmament with scores for a wide variety of stage projects.

In the book, they drop theatrical references throughout the book. When they began to produce other artists, including the Greek-chorus-style pop group The Shangri-Las, Leiber and Stoller wanted to be credited not as producers but as “directors.”

Plus they approached pop songs as little plays. Here’s how Stoller describes the writing of the Peggy Lee classic “Is That All There Is?” (Lieber had crafted the song’s despondent spoken-word verses after reading Thomas Mann for the first time.):

Stoller: Jerry and I had been talking about stretching out as writers, and when he gave me these verses I saw this as the perfect vehicle to do just that. Jerry’s vignettes ached with the bittersweet irony of the German cabaret. I wrote music that I hoped caught the spirit of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht.

Then we got a call from Hilly Elkins, who was managing Georgia Brown. The English singer-actress known for “As Long as He Needs Me” was finishing her Broadway run of Oliver! and heading back to London for a TV special. She needed a song. When she heard those vignettes, she was convinced that that was it—except for one thing.

“It needs a chorus,” she said, “something for me to sing between verses. The spoken parts are beautiful, but it needs something else.”

Jerry and I agreed. We happened to have a chorus lying around, a leftover section from another song that didn’t work. It came complete with lyrics. We played it for Georgia and she loved it.

Leiber and Stoller worked hard on the score of a musical based on Mordechai Richler’s The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. The show died in try-outs, the songwriters claim, because Richler wouldn’t take the time to fix his libretto. They also wrote the yet-unproduced musical Oscar, based on the Peter Finch film The Trials of Oscar Wilde, working directly with the film’s director Ken Hughes. They quote two of the songs in their Hound Dog book: a rant for Lord Queensbury, which begins “Homosexuals, oh, how I hate them, oh, how I loathe the bloody lot/ Why don’t they just exterminate them, exterminate them on the spot?” and a ballad titled “The Love That Dare Not Speak Its Name.”

The Hound Dog chapter about Smokey Joe’s Café begins with mentions of much more audacious musical stage projects that never came to be:

Stoller: We weren’t thrilled that out many attempts to get a musical on Broadway had been in vain. Other efforts like The International Wrestling Match, songs we had written to turn an off-Broadway [sic] play—a Brechtian apocalyptic melodrama—into a musical, hadn’t taken off.

Yet having wanted to crack the format of book musicals for decades, when Smokey Joe’s Café began gestating, Leiber and Stoller insisted that it not have a book, that “the songs are their own stories.” They fell out with a choreographer/director over this exact point during workshops in Chicago, which led to Jerry Zaks coming in as director and agreeing that no book was needed.

Mark Jacoby’s Wicked Wizard Hits Hartford

Mark Jacoby had never seen Wicked until he learned that he’d be auditioning for the role of The Wizard in the musical’s first national tour.

“The Wizard is not a big part, but it’s an interesting part. It’s more sinister than the Wizard in The Wizard of Oz. It’s political. Part of the success of it is the recognition of what power is. Good and evil. How do we define goodness?”

Jacoby’s not only continually intrigued by the intricacies of the role, he’s still staggered by the phenomenon that Wicked has become. “It plays like gangbusters everywhere. It’s beyond successful.” The tour returns to Hartford’s Bushnell Aug. 24-Sept. 11.

“There’s a generation of people now more familiar with Wicked than with The Wizard of Oz—the work on which it’s based, by way of Gregory Maguire’s audacious novelistic update, adapted for the stage by Stephen Schwartz.

“This has become the source,” Jacoby continues. “Though there are lots of tongue-in-cheek references to The Wizard of Oz for those who get them.”

With the show still packing huge venues, is it possible for its performers to sense how well some of Wicked’s well-crafted social satire goes over? “There are some political things, some social commentary things, that always get a reaction, but with theaters this size, it’s sometimes hard to gauge. That’s not to say that there’s never any variation. The Buffalo audience, you could say, was not as expressive as Florida’s. But it starts on this very high level; the show always gets this overwhelming reaction.”

When I mention how much I enjoyed Jacoby’s performance as another bumbling authority figure, the preening movie producer in a rare revival on the musical On the Twentieth Century at the Goodspeed Opera House over a decade ago, Jacoby launches into an astute analysis of why that show never caught on. “It’s too similar to Kiss Me Kate—the plot is similar, the design is similar… they even both have leading ladies named Lily.”

When asked if he has a list of dream roles he’d like to play, Jacoby says he generally doesn’t indulge in such wishful thinking, but that he would like to shed his musical-theater trappings sometime and do a production of the Yasmina Reza standard Art. He’s not even that picky who he plays in it, figuring he’s appropriate for two of the three roles in the chatty comedy.

A cerebral three-person play about a plain white painting would be a sea change from inhabiting the Emerald City. As popular as Reza’s Art has become, Jacoby notes that “when they first put Wicked in Chicago, they thought it would run four to six weeks. That became three years.” The first national tour of Wicked has been going for over six years now, and has stopped in Hartford several times.

Jacoby’s only been with the tour for eight months. “I haven’t toured like this in decades,” he says—it’s his first major national tour since Rupert Holmes’ The Mystery of Edwin Drood in the ‘80s. “I did a couple of productions which were technically ‘tours,’ but they were really just in one city. I did Phantom of the Opera in Chicago for nine months. Same with Show Boat”—the mid-‘90s revival of the Kern/Hammerstein classic, in which Jacoby played Gaylord Ravenal. (Show Boat is, of course, currently playing at the selfsame Goodspeed where Jacoby rode the Twentieth Century. The Cap’n Andy in that production is Lenny Wolpe, who played the Wicked Wizard himself on Broadway.)

Wicked producer David Stone has regularly recast the show in order to keep it fresh. “Wicked, having become the huge show that it is—a lot of people who’ve done come in and out of it. I think management likes to shake it up,” says Jacoby, who previously worked for producer Stone in the Brian Stokes Mitchell revival of Man of La Mancha.

“During one week of the show’s 10-week stand in Washington D.C. at the Kennedy Center, “we had 12 hours of rehearsals,” Jacoby explains.

“Quality control is a big thing in this company. And in the whole Wicked world.”

Colin Quintessence

Colin Quinn's Long Story Short shifts from New Haven to Chicago this week. Photo by Carol Rosegg from the New York production.

Colin Quinn ends his two-week stand of his one-man show Long Story Short at Long Wharf with two performances today (Sunday the 21st, 3 & 7 p.m.), than heads to Chicago’ Broadway Playhouse Aug. 24-Sept. 10, where I imagine his fiercely friendly discourse on a slew of failed (or just plain funny) social systems will go over like gangbusters.

I did a phone interview with Quinn a few weeks ago. “I like to talk,” he said. “I like to provoke. The world is so politically correct. I want to bring out what’s undiscussed…. Though I wouldn’t say business has been clamoring for my point of view.” He means the TV business, which embraced him briefly as the anchorman on Saturday Night Live’s Weekend Update (his tag: “That’s my story and I’m sticking to it”), and as the host of Comedy Central’s Last Call With Colin Quinn.

Club dates could be frustrating for him too. “Stand-up audiences get drunk. The way they set the clubs was just bad. In clubs, people are facing each other.”

When I observe that’s his routines are smart, Quinn sighs “That doesn’t help either.”

But in the theater, his mannered, structured, longform common-sense commentary on current events (and eons-ago events) plays beautifully. Bolstered by Jerry Seinfeld’s active involvement as director (“This guy spent more time on this, for nothing”) and strong reviews from the original New York run, he’s found audiences reliably receptive everywhere he’s played. “Sure, I did it in the Hamptons, Philly and Montreal. The Hamptons, it was a more politically correct audience than the other places, but they were all pretty much the same.”

Describing the act as concerning “Richie Rich, Poory Poor” and international conflicts, Quinn’s working off a tight script but will add new current-events jokes as necessary. Some key material about the Arab Spring and the U.S. deficit near-default was jumped in since the New York run.

The rehearsed rhythms can actually be comforting. Or as Quinn puts it, “Spontaneous can be great, but it can also be smoke and mirrors.”

But he also clearly thinks well on his feet. He deflected a mic glitch at the Long Wharf deftly, even though technical problems could really skew the flow of his mock-irritable oration.

When I ask specific questions about the difference between his theater and club performance experiences, Colin Quinn quickly considers the question, then spits out a marvelously articulate thought-through response about how he felt trying to break through to stand-up audiences with his heavier concepts and material. He describes his frustration, how the set-up of the clubs was an obstacle, how it was an uphill battle. He ends with a metaphor drawn from the same militaristic vocabulary with which he smartly peppers Long Story Short: “I’m not gonna not do stand-up, but it got hard doing what I wanted to do.”

“ I was like an arrogant colonialist. I’m gonna civilize these people!”

Right after this bravura answer, so eloquent he could have been reading it off a page, he says “Congratulations. I’ve done a lot of these [interviews], but nobody’s ever asked me that before.”

I’m beaming, of course, but moreover I’m just impressed. This is the essence of Colin Quinn: fiery, unfiltered, concise, clear, to the point, in your face and unfailingly polite.

Your friend who fills you in on the tough facts: Things have been bad for a while. You have irrational rage problems; we all do. Life’s not fair. Hollywood gets it wrong. You should have paid attention in history class. Your country may be cheating on you. We need a few more drinks to get over this.

This is the guy I want to talk about the fall of civilization with. Long may he reign.

The Wine Peep Through Their Scars

Two theater references in this short London Times editorial regarding AC/DC’s full-band endorsement of a line of Warburton Estate wines. Vintages include Highway to Hell Cabernet Sauvignon.

AC/DC are merely following a path trodden by other one-time hellraisers. A journey from consuming substances so toxic they make lab rats go blind to marketing your own merlot is rock’n’roll’s version of Mrs. Patrick Campbell’s journey from the hurly-burly of the chaise longue to the deep deep peace of the marital double bed…

In rock’s rendering of the seven ages of Man, AC/DC have progressed from the first (“mewling and puking” after a night of hedonistic excess) to the sixth (“lean and sliuppered pantaloon,” sipping a Sancerre). All that now awaits the band is Shakespeare’s seventh age: that’s the one “sans teeth.”

—Grapes of Rock, op-ed, Wednesday, Aug. 17, Times.

My question now, is what are we supposed to do with these old AC/DC pint glasses?

City of Angels: Population 21 (playing 48)

Goodspeed’s announced the cast for their season-ending production of City of Angels (Sept. 23-Nov. 27). It’s a show that warmed the heart of Connecticut, since the original Broadway production won a Tony for Fairfield County resident (and diehard Westport Country Playhouse supporter) James Naughton. The first national tour which played the Shubert Theater in New Haven is also fondly recalled hereabouts, because it starred Barry Williams (the young Max Frost in Wild in the Streets, and OK, OK, Greg in The Brady Bunch).

This latest cast is deftly assembled from Goodspeed veterans who also have big-city musical and touring chops. D.B. Bond, who plays Stine, toured in Legally Blonde, Dirty Rotten Scoundrels and even in the title role of The Scarlet Pimpernel, and served Broadway in the casts of The Phantom of the Opera and Les Miserables. Stine’s film-noir alter ego Stone will be Burke Moses, of the sprawling Goodspeed production of Seven Brides for Seven Brothers and seen on Broadway in The Frogs, Kiss Me Kate, Beauty and the Beast and Guys and Dolls. Moses has played Stone before, in 2006 for the Reprise! Broadway’s Best series at UCLA’s Freud Playhouse.

The double role of Bobbi and Gabby is played by Laurie Wells, Diva Dorothy Brock in the Goodspeed’s 42nd Street. Liz Pearce—Velma in the U.S. and U.K. tours of the critically underappreciated Scooby Doo in Stage Fright (concocted by Jim Millan of Canada’s Crow’s Nest theater, assisted by Mark McKinney of Kids in the Hall/Slings and Arrows). The Goodspeed resume of Nancy Anderson, who plays Donna/Oolie, stems back to ‘90s productions of Sweeney Todd and By Jeeves. Jay Russell (Lincoln in Paula Vogel’s A Civil War Christmas when it world-premiered at the Long Wharf Theatre) is Buddy Fiddler/Irwin Irving. Jeffrey David Sears, City of Angels’ Jimmy Powers, was in the ensemble of a recent Avenue Q tour. Gregor Paslawsky (Lenin in the Long Wharf and Williamstown productions of Stoppard’s Travesties) is Luther Kingsley/ Werner Krieger. Danny Bolero (from the first national tour of In the Heights) is Lt. Munoz and Pancho Vargas. Allen E. Read (Paper Mill Playhouse’s 2009 revival of The Full Monty) will play Peter Kinglsey and Gerald Pierce.

Big Six will be played by Jerry Gallagher. Spencer Rowe will play Sonny. Josh Powell will play Officer Pasco, Del Dacosta, and Gene. Robert J. Townsend will play Mahoney. Christina Morrell will play Margaret and Anna. A young actress Kathleen Rooney, who happens to share the same name as my wife but is completely unrelated, plays Mallory/Avril. Others involved: Michael Keyloun (Dr. Mandril/ Gilbert), Jerry Gallagher (Big Six), Spencer Rowe (Sonny), Josh Powell (Officer Pasco/Del Dacosta/Gene), Robert J. Townsend (Mahoney) and Christina Morrell (Margaret/Anna).

Four-fifths of the a cappella group Marquee Five—Mick Bleyer, Vanessa Parvin, Sierra Rein and Adam West Hemming—has been cast as the show’s back-up vocal ensemble “The Angel City 4.” (The other MF member, not to be at Goodspeed, is Julie Reybur.) Shades of the recent Goodspeed revival of My One and Only, which featured a consistent vocal trio, dubbed The New Rhythm Boys, in a supporting role.

City of Angels will be directed by Darko Tresnjac, who took this gig (and the assignment to direct Bell, Book and Candle at Long Wharf and Hartford Stage) before being chosen as the new artistic director of Hartford Stage a few months ago. Tresnjac directed Carnival! for the Goodspeed last year, and his association with the theater goes back to A Little Night Music a decade ago.

City of Angels is one of those shows that seems more attuned to regional theaters than to Broadway, where it really stuck out in the early 1989 as an alternative to Meet Me in St. Louis and revivals of Shenandoah and The Sound of Music. City of Angels book writer Larry Gelbart was on a roll at the time, stage-wise: his political comedy Mastergate had moved to New York following a regional premiere at the ART in Cambridge.

Looking forward to this one very much.

The Long Story Short review

Colin Quinn in the New York production of his Long Story Short. The New York set has been downscaled a bit for his current run at the Long Wharf Theatre, which closed Aug. 21. Carol Rosegg Photo.

Long Story Short

Through August 21 at the Long Wharf Theatre. Written and performed by Colin Quinn. Directed by Jerry Seinfeld.

The quintessential Colin Quinn is the gruff- sounding yet genial and reflective persona he perfected as the Weekend Update anchor on Saturday Night Live. That gig began auspiciously, with Quinn hurriedly summoned to replace Norm Macdonald, who had just been fired by an NBC exec under the specious reasoning that Macdonald was “not funny.” the firing hadn’t even made the papers when Quinn had to naked his Update debut. He turned the awkwardness into one of the most profound and heartwarming moments in the history of Saturday Night Live, introducing the news segment with a tribute to norm Macdonald, surrounding the experience in terms of working in a bar and having to suddenly take over for the bartender who’d trained and mentored you and then abruptly been dismissed.

For those of us who cherish that gracious, generous, bar- mentality side of Colin Quinn, his one man show Long Story Short has the perfect ending. After an hour of loosely connected verbal vignettes about the rise and fall of great civilizations and the origins of longstanding international and religious hostilities, Quinn brings the show into the present day with a lengthy bit presenting world relations as a bunch of guys in a bar at closing time.

It’s a brilliant bit, full of current- events detail and finely wretched characterizations. As with the whole Long Story Short show, Quinn delivers it matter-of-factly. He doesn’t punch the jokes, overly the characters or otherwise oversell the material. His steadiness, and the complexity of the concepts he’s playing with (

Arab Spring! Israel! British colonization of a quarter odd the world!) makes you listen in closer. Bits that might easily bomb in a stand up sweet in a noisy nightclub play just right on the long wharf mainstage, with Quinn in jeans and black polo shirt standing before an austere arrangement of stony golden steps and a large projection screen.

He also throws in theater- friendly routines like the one about how ths Greeks developed live drama, and soon “the average Greek child stats watching 40 hours odd theater a week.” He follows this with an imaginary meeting between Oedipus and Sophocles, with the aggrieved ruler wondering if the hero of the playwright’ s tragedy was based on him–” because, you know, my name’ s Oedipus and I fucked my mother and killed my father.”

Theater- smugwise, Quinn’s show- opening local-reference gambit is pitch perfect: “All my life I was ‘Ooh, Long Wharf!’ And notes here I am.” When the audience laughs at what may come off as deprecating– Quinn’s show comes to us, after all, after a long and successful run in his native New York, and has previously toured to Canada and Washington DC– Quinn chides the crowd. “I’m serious,” he says, and starts singing the praises not just of the Long Wharf Theatre but of the Long Wharf loading dock.

Colin Quinn is not a clown or an aggressive joke teller. He’s not a natural mimic (though his impression of Tony Bennett is pretty impressive considering that Quinn’s lack of singing skills was the basis of an ongoing routine on the game show Remote Control). His fortune is his working stiff demeanor and delivery. He paces Long Story Short as if he’s pulled up his stool at the bar, signaled a few friends, gotten comfortable, and plans to expound for a while. The 75- minute monologue is smartly broken up with black- outs where Quinn leaves the stage, the projections change, and the audience can applaud or exhale. It’s the equivalent of bathroom breaks or interruptions at the bar. The only thing missing from the loquacious, thought provoking late night mood Colin Quinn has conjured up in the theater is this: You really want to buy the man a drink.

The Show Boat Review

Show Boat

Through Sept. 17 at the Goodspeed Opera House, East Haddam.Music by Jerome Kern. Book and Lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. Based on the novel by Edna Ferber. Directed by Rob Ruggiero. Music Direction by Michael O’Flaherty. Scenic Design by Michael Schweikhardt. Costume design by Amy Clark. Lighting Design by John Lasiter. Choreographed by Noah Racey. Production Manager: R. Glen Grusmark. Production Stage Manager: Bradley G. Spachman. Produced for Goodspeed Musicals by Michael Price.

Performed by Sarah Uriarte Berry (Magnolia), Ben Davis (Ravenal), Andrea Frierson (Queenie), Karen Murphy (Parthy), Lenny Wolpe (Cap’n Andy), Danny Gardner (Frank), Jennifer Knox (Ellie), Quentin Earl Darrington (Joe), Lesli Marghertia (Julie), Maddie Berry (Kim), Paule Aboite, Elizabeth Berg, Elise Kinnon, Denise Lute, A’Lisa Miles, Mollie Vogt-Welch, Kyle E. Baird, Robert Davis, Robert Lance Mooney, Rob Richardson, Greg Roderick, Jet Thomson, David Toombs, Richard Waits, Nicholas Ward, Adam Fenton Goddu and Christiana Rodi.

Oh, this crazy boat we call show.

The stage area of the show boat in Show Boat fills the Goodspeed stage. To show the world outside that show within a boat within a winding river within a changing country at the end of dawn of the 20th century, director Rob Ruggiero has cast members run up and down the theater aisles. He has slaves stand ominously at the back and sides of the auditorium, watching important dramatic developments.

With some shows, this would be too much. But Show Boat has a scope and richness that demands that it be experienced on as many levels as possible.

If they don’t make ‘em like Show Boat anymore, that may have something to do with Edna Ferber, on whose novel the show is based, having been dead since 1968. They don’t make ‘em like Stage Door, Royal Family or Dinner at Eight anymore either. And why did it take so long for something to make a musical out of Giant (coming to the Dallas Theater Center in January, presumably en route to a New York premiere at the Public)?

To say that Show Boat is heavier, deeper, broader, wetter than a lot of other musicals of its time doesn’t really say much. Other musicals of the time weren’t based on 400-page novels by Edna Ferber, who was not just a robust prose stylist but a skilled dramatist, especially when it came to stories about show business.

Rob Ruggiero has accessed several versions of the Showboat script—a document much revised over the years. He’s wisely restored bits which purposefully make you uncomfortable—bits which show that even the most well-intentioned characters are beholden to the racist, sexist and classist biases of the era. Bits which demonstrate how, despite the presumed freedom and independence which Cap’n Andy’s Show Boat has, floating down the Mississippi and stopping to entertain folks along the way, the ship and its inhabitants and firmly affecting by the real-life strugglies going on onshore.

Ruggiero’s rich, rewarding, warts-and-all approach reminds me of Gordon Edelstein’s exceptional revival of The Front Page nearly a decade ago at the Long Wharf Theatre. As with that Ben Hecht/Charles MacArthur classic (of the same Algonkuin Table Broadway era as Ferber’s work), you can strip away the sexist remarks and the racist tendencies and the grittiness, but where do you stop and still maintain the realism which distinguished the show in the first place? Show Boat’s uncomfortable moments are woven into the very fabric of its thick curtains. Just having Joe sing “Old Man River” doesn’t cut it. Including the irony and humor of having Joe’s wife describe this vibrant man as shiftless and lazy, buying into the vernacular and stereotypes of the time while also downplaying his poetic observation skills, adds nuance to this understated character. What else adds to Joe’s character? A full-bodied portrayal by David Aaron Domane, in which his periods of onstage silence and reflection speak as loudly as his booming baritone singing voice.

In trimming Show Boat’s cast to fit on the concise Goodspeed Stage, Ruggiero has maintained enough black male chorus members to keep Joe company, giving the show an ensemble burst of class struggle right at the outset, with a rousing round of “Colored folks work while the white folks play.” The script revision used here is not afraid of the n-word if it serves the plot (and it does).

Sarah Uriarte Berry as Magnolia, Lesli Margherita as Julie, Andrea Frierson as Queenie and David Aaron Damane as Joe in the Goodspeed Musicals production of Showboat. The show's run has been extended through September 17. All photos accompanying this review are by Diane Sobolewski.

The many ways in which the 1951 Technicolor movie scrubbed and streamlined the plot did Ferber’s sprawling narrative a real disservice. The stage show resonates so strongly because the characters grow and change. Little Kim (so named because she was born on the river at the intersection of Kentucky, Illinois and Mississippi) grows into a young woman, smart and confident enough to boss around her no-nonsense grandmother. That amusing development, which virtually ends the show, helps Show Boat end on a note of progress and new adventures, not just the sorry shmaltz of the motion picture version.

Men in this show are constantly being forgiven for grievous wrongs they’ve inflicted on their loved ones. They’re forgiven just because they show up with hangdog expressions on. Ruggiero and the cast understand that this is not something you can hang a show on anymore. They find the depth and humanity and expressiveness elsewhere.

Often, it’s right there in the songs. As Julie, subject of a miscegnation subplot, Lesli Margherita creates stirring self-pitying torch song renditions of “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man” and “Bill,” which are all the more plaintive because of the way Ruggiero surrounds her with other cast members, who are only vaguely aware of the subtext. Margherita’s performance is both nuanced and directly, glowingly entertaining. Julie would be a lump if she didn’t keep a spark of spontaneous lust within her, and Margherita keeps that fire burning.

Likewise, Sarah Uriarte Berry as Magnolia, the princess of the Show Boat who becomes a key romantic figure on its stage and off it, isn’t just sweet—she’s grandly sweet, vulnerably sweet, fascinatingly sweet, all-eyes-on-her sweet. The man who sweeps Julie off her sweet feet, well-heeled gambler Gaylord “Gay” Ravenal, is played by Ben Davis not as a drop-dead handsome blusterer in the old Howard Keel mold but as a flawed yet attractive mortal whose weaknesses are immediately apparent. Gay takes Julie for granted, but she mothers him back; it’s a believable relationship in which both are culpable—though he’s much worse, no question.

With all this melodrama—the doses of tragedy unusual for a musical theater piece written in the 1920s, when the genre was still known as “musical comedy” and dark stuff was intended for operas—a certain overarching lightness is required to put the whole Show Boat show over. That touch comes courtesy of the delightful Lenny Wolpe, who accesses his whimsical Wicked/Little Shop of Horrors/Drowsy Chaperone side to show us a relentlessly upbeat and hopeful Cap’n Andy, who commands his ship with a ruthful, velvet fist. It’s a pity Andy isn’t given a song (it’s always been a role reserved for personality-based comic actors). But he does get to dance with his daughter, and it’ll break your heart.

Lenny Wolpe and Karen Murphy as Cap'n Andy and Parthy Ann Hawks in the Goodspeed's Show Boat. Photo by Diane Sobolewski.

The Goodspeed shows us how Show Boat still overwhelms and carries us along, even when we cringe at bygone attitudes and creaky, ridiculous attempts to redeem or excuse horrifying behavior. The trip depends as much on detours—strong brief appearances by minor characters allowed to steal scenes, brash brass-heavy arrangements of familiar tunes played with the fervor of New Orleans jazz bands—as it does on the main event. This Show Boat literally spills off the stage and makes us deal with life’s realities as well as its escapes.

Rock & Roll Acting School

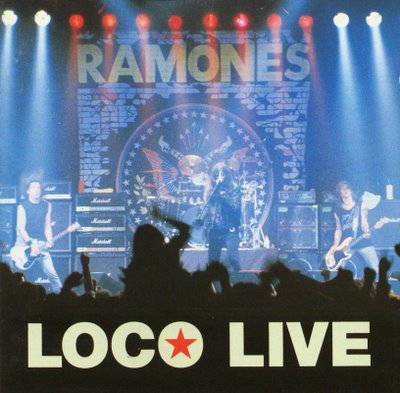

I liked a stage show and to me The Ramones were very theatrical because they didn’t move. You had all these guys doing theatrical stuff that was so excessive, yet The Ramones were getting more out of Joey moving his leg. They would just stand still. Joey would move his leg. Johnny would jump once or twice and they would just make the right moves. It was minimal, the whole approach. It was the way they dressed, the way they moved. It was the music. They had everything: the image, the sound, the lyrics. They were the whole package. I’d never seen any band that had everything together like that.

—John Holmstrom, quoted in On the Road With The Ramones by Monte A. Melnick and Frank Meyer (MJF Books, 2003)