It’s a regular psychodrama film festival live onstage this theater season.

First Persona at the Yale Cabaret. Then It’s a Wonderful Life at the Long Wharf. And now David and Lisa, tonight and Friday at 7 p.m. in the Arts Hall of the Educational Center for the Arts, 55 Audubon Street in New Haven.

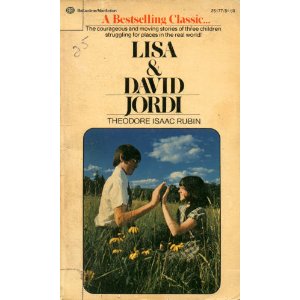

David and Lisa was a fictionalized case study by psychiatrist Theodore Isaac Rubin before it was a 1962 film directed by Frank Perry. But it’s the screenplay, by Eleanor Perry (Frank’s wife, who packed a Masters degree in psychiatric social work herself) which most deeply informed James Reach’s 1967 stage version.

One thing the play keeps from the film is its massive supporting cast. There are roles for at least 22 actors. Which makes it a long shot for a major professional revival but ideal for school groups.

The students at the ECA, the arts magnet high school at the corner of Audubon and Orange streets in New Haven’s so-called “arts district,” have been working on David and Lisa since the project was first announced and cast last spring. I met with them and their instructor/director Joan McAfee during a rehearsal earlier this month.

One of the challenges of doing David and Lisa now is making the plot—about a young man who has a thing for clocks and a fear of being touched who befriends a young woman with a split personality—palatable for audiences who now have a deeper understanding of psychology and personality disorders. Aspects of the script seem sorely dated, and some of the disorders dramatized in the play which barely had names in the 1960s are commonplace now.

To flesh out what is essentially a romance in an unusual setting, a residential treatment center for children with mental issues, the ECA students hit the psych texts. They read the original Theodore Isaac Rubin book. They researched “anything on mental illness that interested them,” McAfee says. They created backstories for their characters, some of whom barely exist in Reach’s script but now have active onstage lives of their own. One student, Chelsea Evered, created a silent character, Sandra, who suffers from bulimorexia.

Max Kruger-Dull, who plays Mr. Clemens in the play, has a mother who’s a real-life psychiatrist, and she came to speak with the cast.

The actors assuming the title roles—Henry Ayres-Brown as David and Jenny Grober as Lisa—did netutral mask exercises and such, but also a lot of academically minded prep. Ayres-Brown says “I read the[Rubin’s] book, a lot about David. How he goes so quickly to extremes. Grober says she watched the multiple-personality melodrama Sybil, read David and its sequel David Today, and “scoured my psych book and the Internet.”

The others found their footing with audacious improvs, one of which involved a streetpole in Leeney Plaza outside their rehearsal space and some bemused passersby. Tyler Roberts, whose patient character is Robert, says “We really got into it. It really helped define what we do on stage.” Bridget Johnson, who plays Josette, adds “It was like having different entities. We got so into it, we forgot we were ourselves.”

The teens go on and on about the process of “Letting down you filter,” how “we all have a little of these disorders in us,” how they’re looking to do more “theater for social change,” how they can relate the stigma some of the patients in the play feel to their own lives, and how they learned to “separate someone from their mental illness.”

Says Erika Conte, who plays Kate, “We want to bring these characters justice.”

The students playing therapists and parents in the show felt no less strongly. Some created backstories where their characters realized they were in the wrong profession. Mara Rothman believes that her character, Barbara, “is very intelligent but doesn’t understand what she’s trying to do.” Leah Rosofsky, who plays Maureen Hart, says she had to “figure out what a therapist can and can’t do.” In the interest of dramatic balance, Rosofsky found Maureen becoming “more comic relief.”

Ah, the wonders of a focused drama program and a months-long ensemble rehearsal period! Given the amount of work that’s gone into it, it’s tragic that David and Lisa has a mere two-evening run at the ECA Arts Hall. Then the theater students move on to the spring project, Carlo Gozzi’s commedia touchstone The Green Bird.

The students have a lot to bring away from this extensively researched fleeting performance experience, however, the sort of shadings and nuances which actors who must be hustled into the roles for productions without such luxurious rehearsal time might never discover.

Mara Rothman suggest that “the most relateable line in the show” is one spoken by Jennifer Grober as Lisa. One of Lisa’s split personalities can only speak in rhyme, and when asks what she’s feeling remarks:

“Not sad. Mad. Not bad.”

The students of the Educational Center for the Arts can illuminate that for you.