The Fatal Eggs

Through September 29 at the Yale Cabaret, 217 Park St., New Haven. (203) 432-1566. Director/adapter/puppetry: Dustin Wills. Adapter: Ilya Khodosh. Producer: Melissa Zimmerman. Stage Manager: Alyssa K. Howard. Scenic Designers: Kate Noll, Carmen Martinez. Lighting Designer: Meredith Ries. Costume Designer: Nikki Delhomme. Projection Designer: Solomon Weisbard. Co-Sound Designers: Joel Abbott, Matt Otto. Music Director: Dan Schlosberg. Technical Director (Ground): Nicole Bromley. Technical Director (Air): Dan Perez. Assistant Lighting Designer: Justin Bennett. Projections Advisor: Michael F. Bergmann. Printing Master: Ted Griffith. Performed by Chris Bannow (Professor Vladimir Ipatevich Persikov), Sophie von Haselberg (Pyotr Stepanovih Ivanov, Manya Faight, et alia), Dan O’Brien (Vlas, Pankrat, Watchman, et alia), Ceci Fernandez (Alfred Bronsky, Marya Stepanovich, Matryona, et alia), Michelle McGregor (Wdiow Drozdova, Dunya, et alia), Mamoudou Athie (Alexander Faight, Fat Man, et alia), Ilya Khodosh (Narrator), Gabe Levy (Voice on Radio).

There’s this wonderful phrase that the Yale Cabaret has been using on and off since the Becca Wolff regime of five years ago. To encourage experimentation and enhance the extracurricular aspects of the Cabaret, programs for the shows began to use asterisks to note members of the creative team who were taking roles or titles outside their specific academic field of study at the Yale School of Drama.

The phrase, as it is currently used in the program for the Cabaret’s 2012-13 season opener, The Fatal Eggs: “working outside discipline.”

And what a glorious term it is to describe The Fatal Eggs.

To do Russian comedy properly—and they do, they do—this show’s cast must do a lot of things which professional acting schools often frown upon—quick changes, cartoon voices, loud costumes, angular physical shtick, and the juggling of constant danger-elements like unwieldy props and wheeled furniture. The whole show seems exhilaratingly on the edge of collapse for the entire time it’s happening. The chaos perfectly conveys the story Bulgakov is telling.

The tale’s not exactly new—you could relate it everything from the myth of Icarus to the Kids in the Hall film Brain Candy. A scientist makes a breakthrough discovery which is instantly coopted by government, big business and the media, with catastrophic results. The art is in the telling. There’s a radical, riotous pacing to this cautionary tale that blends precise comic dialogue with anything-can-happen anxiety. It begins with screams and flusters of Grand Guignol intensity, then settles into confident vaudeville routines.

The writing matches the wackiness of the staging. Here are two scientists chatting about what to do with the remains of a lab experiment:

“Shall I bury it?”

“Defenestration seems more spirited.”

It helps a bit that Mikhail Bulgakov is working “outside discipline” as well. The Fatal Eggs is not one of the great writer’s playscripts but an adaptation of one of his short stories. This gives lots of dramaturgical wiggle room to the co-adapters, Dustin Wills (who directed the production and designed its chicken rod-puppets and other fabricated effects) and Ilya Khodosh (who goes “outside discipline” as the show’s onstage narrator, having memorized long tracts of exposition). Many Russian stage satires of this ilk get more and more frantic, to the point of madness and explosion. This one gives itself a chance to slow down. Once the terror of global biological upheaval sets in (frogs and snakes and chickens and ostriches are among the afflicted), The Fatal Eggs allows itself to catch its breath. It doesn’t stop being crazy-funny, but it allows for comic pauses and pensive-thought poses which would have stalled the frenzy of earlier scenes. Best of all, it lets you leave the theater having absorbed a message rather than just having taken a ride.

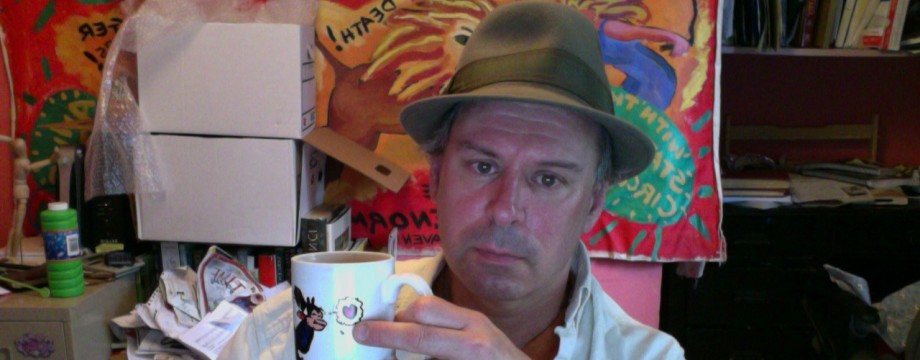

The actors mesh brilliantly with the staging and design. Everything has an old-school natural feel. Effects are old-school: puppets, overhead projectors, teetering piles of books and scientific devises and other crap. Similarly, the actors don’t “project” in the modern performance manner; they jut out, jab, fling and yelp like burlesque comics. This is established century-old Russian comic cabaret style, and the half-dozen main performers (covering dozens of roles, from servants to high government officials to honest country folk and scientist wizards) latch onto these surefire old comic techniques as if they were raised on them. Chris Bannow, as the scientist whose discovery sets the plot in frantic motion, admirably maintains a position in the center of the storm by being neither too kooky or too straightmanly. Ceci Fernandez and Mamoudou Athie stand out among the supporting ensemble for creating grand, showstoppingly hilarious, comic exaggerations out of parts which are largely there to fuel the plot.

Kodosh and Wills’ script helps the actors play big by revising Bulgakov’s story down to a few enclosed sets, and letting every single character get a big splashy entrance.

This is a finely tuned machine of mirth, menace and manic social satire. It’s a great way to start the Yale Cabaret season, and also a terrific transition from the similar (though less sensationally silly) Yale Summer Cabaret season of ensemble storytelling-themed shows.

When you scan the production credits above (for the record, Solomon Weisbard and Meredith Ries are also, like Khodosh, “outside discipline”), give special attention to the title Printing Master. I assume Ted Griffith is the guy who concocted the extraordinary fake Russian newspapers, whose tabloid headlines propel the plot as capably as does Khodosh’s narration (or, indeed, as does the late-in-play radio broadcasts stentoriously intoned with life-in-wartime aplomb by Gabe Levy). Off-stage, there’s also some print media to praise: I love how the program (presumably the work of this season’s graphic design team of Julia Novitch and Jessica Svendsen ) folds out into a little poster. I also dig the profusion of print—fliers, posters, photos and other epherema—which now adorn the Cabaret staircase as you stand in line at the box office.

This is a theater that truly respects text. And, odd as it seems in such a mad endeavor, honors discipline, inside and out and upside down.