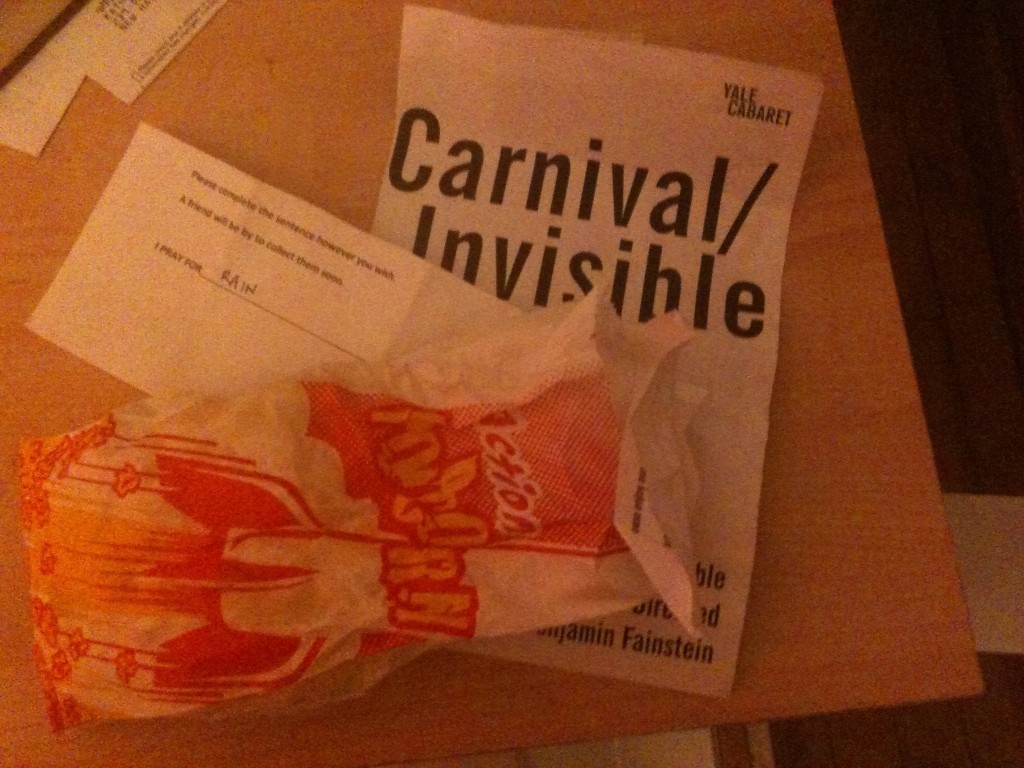

Carnival/Invisible

Through April 14 at the Yale Cabaret, 217 Park St., New Haven. (203) 432-1566.

Created by the Ensemble. Written and directed by Benjamin Fainstein. Lighting & Scenic Designer: Edward T. Morris. Costume Designer: Nikki Delhomme. Dramaturg: Caroline V. McGraw. Stage Manager: Jenny Schmidt. Technical Director: Daniel Perez. Producer: Shane Hudson. Performed by Merlin Huff (Barker Masterful Majestic), Hannah Sorenson (Dustbowl Diana), Carly Zien (Applejack Amanda), Tim Brown (Cotton Candy Cameron), Chris Bannow (Popcorn Peter), Whitney Dibo (Terracotta Tina) and Brandon Curtis (Sausage-on-a-Stick Sebastian).

It’s hard to see any show based on the Chautauqua variety-show stylings of the late 19th century without recalling the brilliant, spellbinding show Chautauqua! devised by New York’s National Theatre of the United States of America, which played at New Haven’s International Festival of Arts & Ideas two summers ago. The NTUSA show was notable for respecting the full traditional Chautauqua menu of guest speakers, local content, melodrama, clowning and moral turpitude—then deconstructing itself before your eyes.

This Chautauqua effort, Carnival/Invisible, has less spectacle and and a narrower focus, but no less irony and analysis. Boffo clowns turn on each other. Suggestive puns are left to simmer. There’s dancing, and Greek tragedy, and hurled popcorn, and a goat-urine elixir. Chaos ensues, so that calm can be dramatically regained.

Given the trad formats and earnest appeals of classic Chautauqua, it’s natural to want to pull the thing apart, I guess. But what does that say about the jaded nature of modern American theater, when these same styles of presentation and entertainment are still packing them in to churches and community centers nationwide without any snarky elements?

The late Thursday night performance of Carnival/Invisible was particularly enlightening because it behaved so much like a true tent show of a century ago. The audience was volatile—generally respectful, but vocal and abrasive. The show followed a ceremonial changing-of-the-guard at the Yale Cabaret, with the just-announced slate of artistic and managing directors toasting the current holders of those positions on the “YSD Night” performance of the last Cabaret show of this school year. Much beer and wine and bourbon had been consumed at a party just before the performance. The merriment surrounding the ceremony, which involved Yale School of Drama Dean James Bundy in a fireman’s outfit, would not subside. The show’s interlocutor, Barker Masterful Majestic played by Merlin Huff, maintained imperturbable cool but also withdrew the promise of one sensitive scene because “Unfortunately, ladies and gentlemen, you are too unruly.”

The performers dealt with the raucous crowd just as real touring Chatauqua companies might. They exercised patience and forebearing. They occasionally shushed the louder folks. They made gentle fun of hecklers. And they got on with it. There are tender moments to this fragile display which nearly got steamrolled by the crowd’s oversized reactions to everything. But the cast’s intensity, and its anxiety, added emotional depth and kept the show on track. In any case, conceiver/director Benjamin Fainstein understands the power of unleashing several verses of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.”

This was a nice show to end the current YSD season on. It dovetailed nicely with other ensemble-devised works the Cabaret has showcased this season, hearkened back to simpler times of minimal design, and to longtime Cabaret-goers like myself it evoked a time in the 1990s when just about every season ended with a circus-type affair.

The evening, from the passing of the torches to the incendiary response to the performance, showed what an important place the Cabaret has become. I recall when it really was mainly an experimental lab for student’s extracurricular projects, with the audience and the food service kind of an afterthought. In the past decade it’s become a key part of the Yale School of Drama experience, not just ground zero for important new theatrical statements but a proving ground for performers—especially when faced with their exuberant classmates.