It’s hard to describe what it was like in the late 1980s and early 1990s, to see plays by Vaclav Havel produced at the Yale Rep and at college theaters throughout the country, while their author in the midst of transforming a communist country into a democratic republic and EU member now known as one of the most peaceful countries in Europe.

It felt like theater had meaning for anyone, could change things anywhere. Someone had used what he’d learned as a theater practitioner—writing, stage managing, building—to enhance his own abilities to communicate, and to broaden and vary the crowds he could communicate with.

Havel was a playwright first, and not just chronologically in his abruptly changing career. His writing was not some quirky early entry on his resume, or an amusing avocation. Havel was not like that Pope who happened to have once written a play, or like George W. Bush’s Attonrey General John Ashcroft composing “Let the Eagle Soar” and performing with the Singing Senators.

Hit Havel’s official website and you’ll see that playwriting is paramount. Upon leaving office a few years ago, he actively returned to playwriting. Both his wives worked in the theater; Olga, who was married to Havel for 32 years and died in 1996, worked with him in the 1960s at Theatre on the Balustrade. His second wife, Dagmar, has continued to act on stage and in movies while she was First Lady.

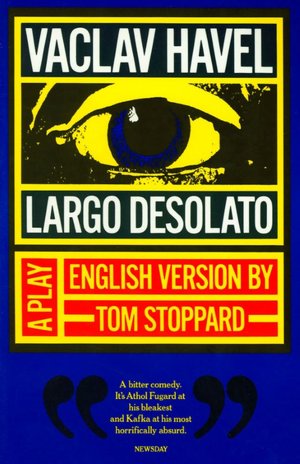

When he was imprisoned as a dissident in the 1980s, the first thing Havel did upon being released was to write a play, Largo Desolato. That’s probably his best-known play in America, thanks in part to the Yale Rep’s 1990 production of it. But there were New York productions of Havel’s early works, including at the Public Theatre, dating back to the 1960s, at times when the plays weren’t allowed to be presented in Havel’s then-Communist homeland. In 2006, while Havel was in residency at Columbia University, the New York-based Untitled Theater Company #61 staged a “Havel Festival” of 16 of his plays—every full-length play he’d written up to that time. When the Wilma Theatre in Philadelphia produced the American premiere of Havel’s Leaving last year, Havel attended opening night.

The theater is where Havel first articulated some of his political viewpoints, and how he first connected to like-minded theorists who saw his potential as a government leader and not just a particularly articulate voice of dissent. When the revolution began in November 1989, theaters willingly went on strike so that their auditoriums could be used for meetings and rallies.

As president, Havel hobnobbed with artists, notably Lou Reed, whose early band The Velvet Underground is said to have been an inspiration in the naming of Czechoslavakia’s “Velvet Revolution.” Again, these were weighty relationships, summit meetings of a sort, not ornamental ceremonies where you drape a ribbon on someone for being famous. Havel treated writers and musicians as ambassadors, taking it as a given that their talents had political purposes and ramifications. In 1990, Havel wanted to make Frank Zappa a special envoy for culture, trade and tourism. (The Bush administration wouldn’t accept the Zappa appointment, but Havel did it anyway, unofficially.)

In his 1984 speech “Politics and Conscience” (which had to delivered at the University of Toulouse-Le Mirail by fellow Czech-born playwright Tom Stoppard because Havel was not allowed to travel), Havel says:

I favor “antipolitical politics,” that is, politics not as the technology of power and manipulation, of cybernetic rule over humans or as the art of the utilitarian, but politics as one of the ways of seeking and achieving meaningful lives, of protecting them and serving them. I favor politics as practical morality, as service to the truth, as essentially human and humanly measured care for our fellow humans. It is, I presume, an approach which, in this world, is extremely impractical and difficult to apply in dailv life. Still, I know no better alternative.