Lindbergh’s Flight

By Bertolt Brecht. Presented by Kate Attwell, Gabe Levey, Brenda Meaney and Mitchell Winter.

Through March 16 at the Yale Cabaret, 217 Park St., New Haven. Remaining performances are Friday and Saturday at 8 & 11 p.m. $15, $10 students. (203) 432-1566. http://yalecabaret.org

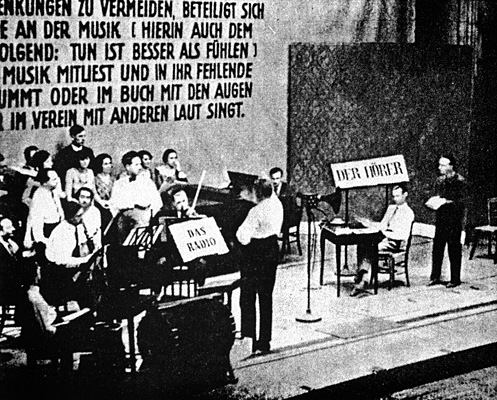

In its time, Lindbergh’s Flight marked a turning point in the theater writings of Bertolt Brecht. It was in some ways the start of the “didactic” style which colored his works for decades afterwards. It was a contemporary “learning play, or Lehrstück, based on a major news event of the time in which it was written: Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 flight across the Atlantic Ocean. The script was presented on radio in 1929, then revised in concert form as a cantata for orchestra, chorus and solo vocalists. It got good reviews and further productions, and Brecht himself thought enough of it to continue revising and rethinking the piece decades after its premiere.

The essential plot concerns the flyer of an airplane describing his preparations for flying acorss the Atlantic Ocean, while some rivals mention their attempt to make the trip first and thwart the flier of his glory. The play’s themes, which extend to the very medium in which it was first broadcast, involve technological innovation and international one-upmanship.

The Yale Cabaret is refueling Lindbergh’s Flight this weekend, in a fresh reinterpretation by Kate Attwell, Gabe Levey, Brenda Meaney and Mitchell Winter. It opened last night and runs through Saturday March 16. (I’ll be seeing the show late tonight, and posting a review here tomorrow.)

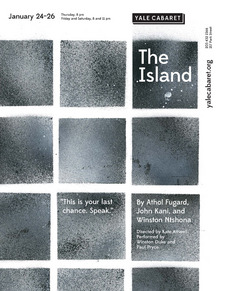

Levey, Meaney and Winter are students in the acting program at the Yale School of Drama. Attwell is in the school’s dramaturgy program but has distinguished herself at the Cabaret as a director, most recently with her triumphant production of Athol Fugard’s The Island. For this production, they’re eschewing titles like “director” and pushing for an ensemble, collaborative outlook.

The team all worked on one of the YSD’s in-class “Drama 50” shows together, and “wanted to work together again in the style we’d created.”

Did that style happen to be didactic mid-20th century German radio opera? Not at all, but when the students went looking for interesting scripts to apply their newfound communal experimental skills to, “somehow the idea of Brecht came up,” Attwell says. I interviewed her and Levey earlier this month at Book Trader about the project. “We started looking at the lesser-known ones, and stumbled across Lindbergh.

“Brecht went through this period of writing short plays about people who are performing the plays while learning about their subjects.” This so-called “learning play for children,” the first in a subset of Brecht’s work dubbed “didactic plays,” was a good fit for their own social/political/theatrical explorations.

With some scripts, when you hear they’ve been reworked from top to bottom, you worry. With Brecht, who wrote about very topical subjects happening in a very specific place in a very specific style at a very specific time of history for a very specific audience, some measure of reinterpretation is always required. “It’s safe to say,” says Gabe Levey, “that we’ve been irreverently reverent.” They were encouraged in their rewrites by the fact that Brecht himself reworked his script a number of times to keep up with changing views about its purported hero and the culture’s sense of how the world could be brought closer together—or dominated—by the power of radio waves and transcontinental transportation. “The number of rewrites that this poor little play went through…,” Levey sympathizes, regarding Brecht’s original manuscript. “And yet there’s only one published text,” of 19 pages in length.

Another key element which changed over time was how Lindbergh is portrayed in Lindbergh’s Flight. At first, Brecht made him a stand-alone character. Then, as world events exposed the aviator’s Nazi-sympathizer side, Brecht revised the play so that the title character’s voice and image were diluted and no longer represented by a single actor. (The title of the play was also changed from Der Lindberghflug to Der Ozeanflug.) “We have been grappling with the narrative of Lindbergh,” Attwell says. “The history of the play is that it goes from one Lindbergh to eight Lindberghs to no Lindbergh at all.” In this rendition, the character is played by “one person, sometimes, most of the time.”

Another wrinkle, adds Levey: “We’re not opera singers. We don’t even know if we could get the rights to perform the Weill music.” During Brecht’s work on it, the play’s musical score by Paul Hindemith (whose outstanding career as a composer and music theorist included decades of influential teachings at Yale) was augmented with tunes by Brecht’s frequent collaborator Kurt Weill. None of this music figures in the Yale Cabaret production.

Oh, and… “[Lindbergh’s Flight] is not even meant to be performed.” Live onstage, that is. It’s a opera written for radio. “The text is lyrics, not dialogue. There are problems we’ve had to solve dramatically.” Adds Levey, with Brechtian portentousness: “All of our devising and aesthetics, all our history, are coming to bear on this.” Some of the solutions come through sound design, dance movement and original music. Cast-wise, the show’s cast and chorus has been modified to a four-person ensemble. “We thought about video, but left that behind.” The show isn’t overtly technical, Levey explains: “All the technical elements you can see in what’s actually being done onstage. It’s like ‘Welcome to our room.’”

Ultimately, though, the show seeks to honor Brecht’s intention, not ironicize or overrun them. As Gabe Levey puts it, choosing his words carefully, “When Lindbergh’s Flight is performed within our show, it is Lindbergh’s Flight.”

That carefully parsed explanation is followed by this: “But Lindbergh’s Flight does not a full theater performance make.” The show as written clocks in at well under half an hour, and even Brecht paired it with another piece to make for a fuller evening. In this case, the length and the nature of the piece invite the addition of other presentational elements which can acclimate it to modern times and performance methods.

Some of the alterations in tone and concept come from the very act of trying to stage the piece at the Cabaret. “There’s inherent humor in it,” Levey says, because of the operatic lyrics, transformed, with fairly with fairly didactic content. There’s that idealism. Brecht writes this in the 1920s. Ninety years later, the ideas are pretty complicated now. We wanted to figure out how to make this work now. How can we be fun and open and communicating with the audience?” They found some understanding just in the attempt. Levey and Attwell quote one of their collaborators and castmates on the project, Brenda Meaney, as saying, “Being in a room with strangers, being totally vulnerable, is a way of being that is totally a political statement.” To which Levey adds, “We’re tickling the idea of actors acting.” The process of creating the show—a fairly lengthy process for a Cabaret project, due to its collaborative nature—was kept upbeat and exploratory. When approaching designers, Attwell and Levey say, they weren’t looking for technicians but for “playmates” whose imagination could help further the collective vision.

Levey has never done a Brecht show before, as an actor or otherwise. Levey was involved in a production of Caucasian Chalk Circle when she was younger. Brecht does get intensively studied at the Yale School of Drama, however, so the Lindbergh’s Flight team feels they’re on firm footing (or walking in the clouds, if you’d rather).

Astute Cabaret-goers can relate the themes of disorienting air travel and finding one’s place in the universe found in Lindbergh’s Flight to original works by Attwell and Levey which played at the Cabaret space in the 2011-12 season. hundredyearspacetrip, a collaborative piece created by the We Buy Gold theater troupe which Attwell co-founded with Nina Segal, was a meditation on life paths not taken, wrapped up in a parable of space exploration. Levey’s solo show Brainsongs, or the play about the dinosaur farm, was, in part, about slowing the world down so it can be appreciated and managed. Both shows blended high comedy with abstractions. Both examined technology, with overt placement of microphones or lip-synching interludes.

The team’s special relationship as classmates and scholars and artists promises a thought-provoking reworking of a rarely-seen yet undeniably important Brecht one-act.

“We’re really excited to put it out there,” Gabe Levey exults. “And meet this weirdo text head-on.”