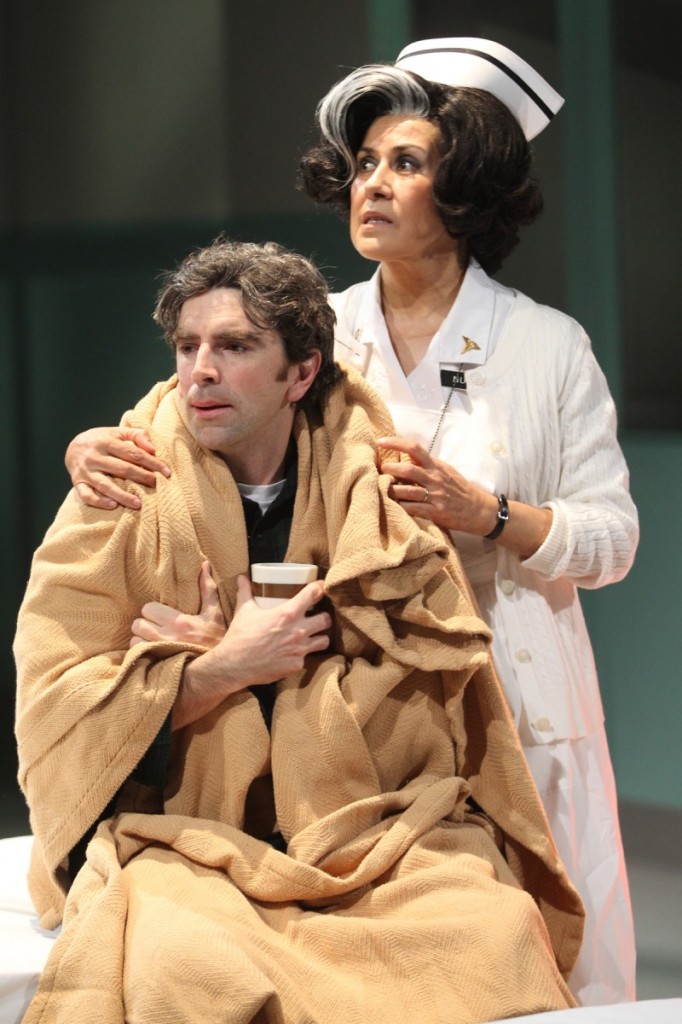

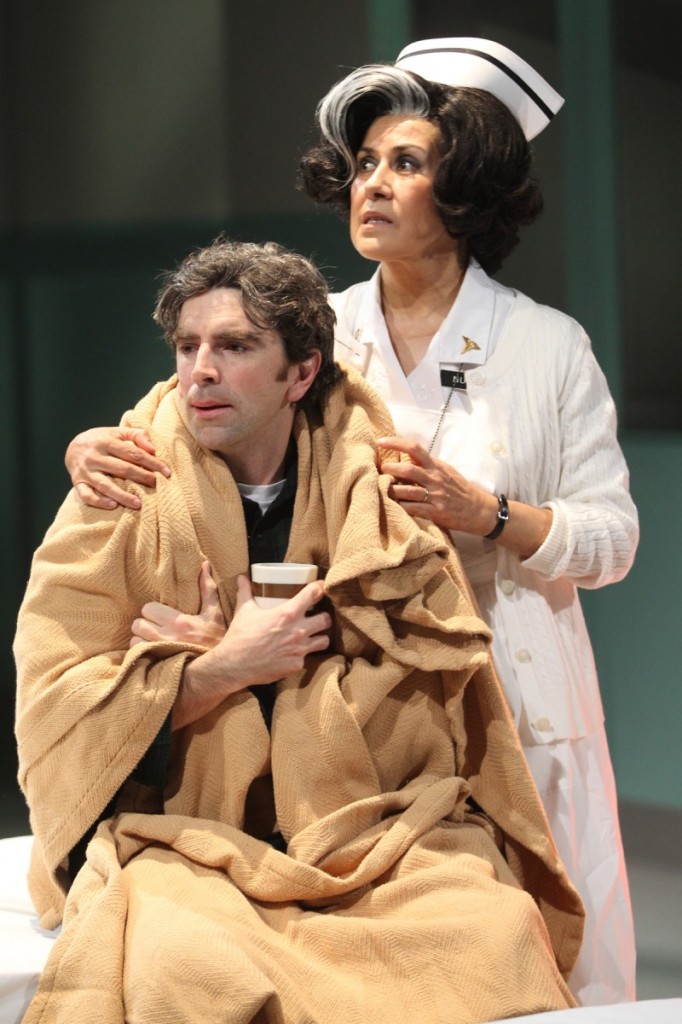

- Soldier 1, and Nurses 1, 2 & 3 in Eric Ting’s production of Macbeth 1969 at the Long Wharf Theatre through Feb. 12. Photo by Joan Marcus.

Macbeth 1969

Through Feb. 12 at the Long Wharf Theatre.

Directed and adapted by Eric Ting. Set design by Mimi Lien. Costume desing by Toni-Leslie James. Lighting design by Tyler Micoleau. Sound design and original music by Ryan Rumery. Fight direction by David Anzuelo. Stage Manager: Lisa Ann Chernoff. Performed by: McKinley Belcher III (Soldier [1]), Barret O’Brien (Soldier [2]/A Civilian), Socorro Santiago (Nurse [1]), Shirine Babb (Nurse [2]), Jackie Chung [Nurse [3]) and George Kulp (A Politician).

There are lots of trinities in Macbeth: The three witches, the slaughter of three male militaristic opponents, the husband/wife/child unity of the Macduffs, etc.

And so Macbeth 1969 (Hey! “69” is divisible by three!), director/adaptor Eric Ting’s arch and angular Vietnam-era reworking of Shakespeare’s tragedy, works on three levels:

• as a clear telling of Shakespeare’s story.

• as a chance to scale down the cast and thus reset the gender balance.

• as a war play fitting to its ’69 time period.

The power struggle is now set in a Midwestern VA hospital during a snowstorm, the glistening medical implements and clinical white sheets providing a decidedly unearthy but exceptionally bloody Birnam Wood. (Can we call this one the “Stat!”-ish play instead of “The Scottish Play”?)

If you’re the kind of audience member that likes to be acclimated in advance, the Long Wharf’s looking out for you. The community outreach on this show has been phenomenal. Local veterans have been consulted on the adaptation since it was in early script form. A core of Long Wharf subscribers followed the entire production process as members of the theater’s Sparks program. You can find a lengthy Macbeth 1969 synopsis in the program—each scene gets its own paragraph, or you can just scan the one-word headers: Waiting, Reunion, Lust, Honor, Celebration, Night, Suspicion, Fear, Ghost, Cure, Traitor, Blood, Haunting, Mourning.

That covers it, all right, and such meticulous yet punter-friendly dramaturgy is symptomatic of a production that dwells in details, details, details.

On one level, this is a two-hour intermissionless burst of creative problem-solving:

Q. How to make the witches witchy in a modern setting? A. Have their “prophesies” be office gossip transmitted via a desktop television.

Q: How to include the death of Macduff’s son when you’ve limited yourself to a sextet of adult performers? A: Make him a fetus.

In order that the same actor can play both Banquo and Macduff (an easy logistical call, since one character dies before the other arrives), Banquo’s head is entirely covered in bandages. This would be an impediment for most actors, but fortunately these two key rivals in Macbeth’s unhinged powerquest have been entrusted to Barret O’Brien. I can attest to O’Brien’s extraordinary powers of connecting to audiences from having seen him play such supernaturally inclined characters as Peer Gynt, Dionysus and Prospero when he at the Yale School of Drama a few years ago.

Barret O'Brien and Socorro Santiago in Macbeth 1969 at the Long Wharf Theatre. Photo by Joan Marcus.

Here, O’Brien’s white cloth-covered Banquo is a ghostly cipher from the get-go. Stuck in his wheelchair, he’s practically part of the set. His ubiquity, and the lack of the usual army of supporting characters in the play, really gives you a fresh sense of the relationships among the characters, and lessens the starriness of the leads. In this scenario, Macbeth’s simply the new, intensely charismatic patient in the ward; his soliloquoies are a lot less interesting than his exchanges with the nurses and visitors. It’s like a Shakespearean One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

McKinley Belcher III in the subdued title role of Macbeth 1969 at Long Wharf Theatre. Photo by Joan Marcus.

The ensemble feel is consistent despite the large number of familiar solo speeches in this play. When those “Tomorrow and tomorrow”s and “dagger I see before me”s and “Damn spots!” arrive, they’re nearly all played quietly and intimately, with onstage observers quietly taking them in. Apropriately, in the script and program for Macbeth 1969, character’s names and ranks aren’t important. We have McKinley Belcher blustering, then reeling as “Soldier [1],” a marvelous portrayal of a battle-ready man gradually losing his nerve. We have the aforementioned Barret O’Brien as the bandaged, vulnerable yet chipper Soldier [2], then returning as “A Civilian” with Pacifist flair on his hippie vest. (As a lifelong pacifist myself, I could bitch about the alacrity with which Macduff disavows those beliefs and picks up a gun, but I get that this is really a statement on societal chaos and contradiction during international conflicts.) Then there are Nurses [1] (Socorro Santiago, who gets a lot of the expositional and body-discovering duties), [2] (Shirine Babb, sultry rather than sinister as Soldier [1]’s conniving lover) and [3] (Jackie Chung, sweet and funny and innocent in a variety of situations). The nurses are attuned and harmonized as finely as a ‘60s girl pop group, yet this is a realistic portrayal of work colleagues and not a chirping Greek chorus a la Little Shop of Horrors.

Such a gentle communal feel is tough to pull off with a play that ordinarily is overpopulated with screaming soldiers. But this is a Macbeth where there are as many female actors (three) as male, and where the feminine energy carries both the horror (the murder of Lady Macduff; the insanity of Lady Macbeth) and the humor (one of the nurses is the knock-knocking gravedigger.)

There are lots of cleverly staged scenes (a bloody melee amid hospital beds) and memorable deliveries (Duncan’s pronouncements made in insincere grinning politician-speak).

But none of the long list of impressive moments can match the effect that first greets your eyes when walking into the Long Wharf theatre mainstage auditorium for Macbeth 1969. Scenic designer Mimi Lien has created a set which is at once hyper-realistic and thoroughly disorienting. The hospital room curtains are at an odd angle with the auditorium, throwing you off visually at once. The sheer scrubbed whiteness of the hospital is a remarkable place on which to set forth such a bloody series of encounters, changing the atmosphere from the usual battlefields to a more inward, psychological, post-traumatic arena. My first mental image of this production will always be of that white set.

Among Shakespeare’s plays, Macbeth is concept magnet. You can see movies where it’s been redone as an American gangster story (twice), a fast-food restaurant brawl and a pop-star odyssey. As for scaling down the cast, I’ve never seen it done onstage with six actors, but I have seen it done with three (Peter Sellar’s memorable blending of the drama with an urn-encased Samuel Beckett one-act, Play/Macbeth in the early 1980s). The point is not that you can lay a cool concept over Macbeth—plenty of directors have done that. The trick, and Eric Ting and his cast and creative team have mastered it, is not just retrofitting the text to that new style but actually finding new things to say within it.

Macbeth 1969 is as confrontational and sympathetic a Vietnam drama as Streamers, Medal of Honor Rag, Hair, or any play from the 1960s or ‘70s you can name. It forces you to think beyond the conventional battle plans of winning and moving forward, and makes you realize how poorly thought through Macbeth’s own plan is. Like the TV-watching witches, it uses shiny surfaces and a variety of viewpoints to show the big blockbuster finish, and the snowy static dead test pattern just beyond it.

Jackie Chung and Socorro Santiago in Macbeth 1969 at the Long Wharf Theatre. Photo by Joan Marcus.